Salman Rushdie Doesn’t Want to Be Your ‘Free Speech Barbie’

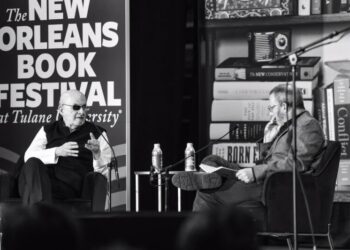

“It’s a subject I’m anxious to change,” the author Salman Rushdie told the Atlantic staff writer George Packer at the...

Kids in hospital help penguins woo mates with painted pebbles

The penguins crowded around a green wheelbarrow, eager to see what was making the clattering noise inside. Moments later, more...

Trump’s UFO release could include videos, photos of non-human craft proving we aren’t alone: source

The federal government holds shocking evidence of UFOs which proves we are not alone — including satellite imagery of out-of-this...

I felt unprepared when I moved into my first apartment. Living alone has been challenging, but also incredibly rewarding.

During my last year of college, I moved into my first apartment alone. Carrie BerkAfter living at home for most...

In Arizona, an Electric Utility Holds an Election, Open Only to Property Owners

In one of America’s least democratic elections, the rule is not one person, one vote. It’s one acre, one vote....

Zohran Mamdani and radical mayors of five other embattled Dem cities plot lefty super group

Six of the most radical leftist mayors in the United States – including NYC’s own Zohran Mamdani – are plotting...

Have trouble falling or staying asleep? Try cognitive shuffling.

When Luc Beaudoin was in college, he was having trouble falling asleep. Beaudoin was studying cognitive science and psychology, so...

America Depends Less on Oil Than Ever

War with Iran has frozen commerce in the Persian Gulf and boosted oil prices by more than 50 percent worldwide,...

Ray Dalio: I’ve studied 500 years of history and fear we’re entering the most dangerous phase of the ‘Big Cycle’

Most people are shocked by what’s unfolding in the world right now. I’m not. I’ve seen this movie before. As...

The Man Behind the Oscars ‘Glambot’

Cole Walliser is not exactly a celebrity, but like many in Hollywood, he has made a career out of his...