Minnesota man accused of bilking $220K from family-run suicide prevention nonprofit founded for his late brother-in-law

An alleged fraudster stole nearly $220,000 from a Minnesota suicide prevention nonprofit he ran with his in-laws since its founding...

Trump’s ‘hokum’ on key issue left Republicans holding the bag after SOTU: analyst

President Donald Trump’s “hokum” on affordability left many Republicans disappointed after the State of the Union, according to one analyst....

‘Sociopath!’ Stephen Miller melts down as progressive podcaster mocks SOTU theatrics

White House senior adviser Stephen Miller and former Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau got into a heated Twitter exchange on Wednesday...

Tech companies are spending an unprecedented $700 billion this year on AI data centers. Nvidia’s Jensen Huang says we’re not anywhere near the peak

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang’s comments on his company’s Q4 earnings call on Wednesday may one day be remembered as the...

‘Sick and pathetic’: Analysts outraged by Republicans’ latest attack on trans people

The latest attack against the transgender community by Republicans in Kansas incited outrage among analysts on Wednesday night. The Kansas...

Park Chan-wook Named First-Ever South Korean Cannes Jury President for 2026 Festival

South Korean director Park Chan-wook has been named president of the 2026 Cannes Film Festival jury, Cannes organizers announced on...

How America Chose Not to Hold the Powerful to Account

Around the world, powerful men are facing consequences for their actions. Former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro was convicted of trying...

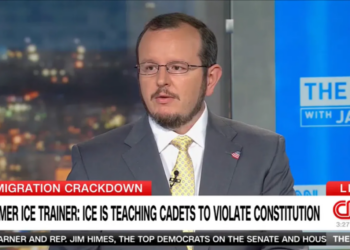

ICE whistleblower reveals ‘terrifying’ warning as untrained Trump recruits unleashed

A whistleblower revealed a “terrifying” warning about President Donald Trump’s new immigration force recruits during an interview on CNN. Ryan...

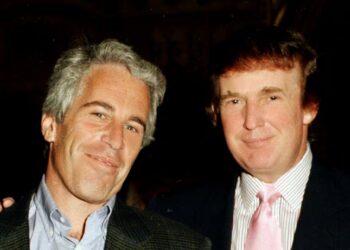

DOJ Cornered on Epstein Files’ Missing Trump Bombshells

The Justice Department has been forced to respond to claims it illegally withheld documents in the Epstein files containing FBI...

Massive wagers on Trump confirming alien life ignite insider trading speculation

Someone in the Trump administration may be trying to profit from the president’s push to release information about extraterrestrial life,...