Iran is now on ‘death ground’ amid existential threat from U.S. attacks and could ‘go big’ in retaliation, former NATO commander warns

With President Donald Trump calling for regime change in Iran, the country’s leadership now faces an existential threat and is...

Bill Clinton on his Jeffrey Epstein relationship: ‘I saw nothing, and I did nothing wrong’

Former President Bill Clinton told members of Congress on Friday that he “did nothing wrong” in his relationship with Jeffrey...

How the World Is Reacting to the Attack on Iran

The response from world leaders to the United States and Israel’s Saturday attack on Iran was a mixture of support,...

Pete Hegseth bans military from ‘woke’ elite universities he attended

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, who earned his master’s degree from Harvard University in 2013, has launched a sweeping campaign to...

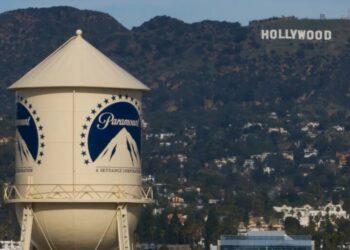

Warner/Paramount sets up Hollywood to shrink from Big 5 to Big 4, a decade after Disney took out number 6

Two of Hollywood’s oldest studios may be consolidating into one. In a shocking twist after a monthslong bidding war, Paramount...

Michael Jackson’s former friends sue singer’s estate for alleged child sex trafficking and abuse

Michael Jackson has been accused of child sex trafficking and abuse, according to a new lawsuit. Frank, Dominic, Marie-Nicole Porte...

Flight diversion map: See where flights are getting rerouted to in the aftermath of the attacks on Iran

A list of canceled flights from the main airport in Beirut, Lebanon, on Saturday. Houssam Shbaro/Anadolu via Getty ImagesMore than...

The U.S. should wage war only when it must. This isn’t one of those times.

My big takeaway from the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq — which I deeply regret having supported — is that...

Popoola twins lead Palisades to City Section Open Division boys’ basketball title

1 p]:text-cms-story-body-color-text clearfix”> When the horn sounded to end Friday night’s City Section Open Division boys’ basketball final, the first...

This Is How Big a Telescope Aliens Would Need to See Dinosaurs on Earth

Roughly 66 million years ago, scientists believe an enormous meteor, dubbed Chicxulub, smashed into the Earth in an extinction-level event...