Cancer, March 2026: Your Monthly Horoscope

You feel it before anyone names it. The lunar eclipse on the 3rd hits your axis of belief, direction, and...

War and Peace Cannot Be Left to One Man — Especially Not This Man

Eight minutes. That’s the length of President Trump’s social media video announcing his war with Iran. He didn’t go to...

‘One Battle After Another’ wins PGA Award for best film. Next stop: Oscars

Paul Thomas Anderson’s darkly comedic action-thriller “One Battle After Another” won the top prize at the Producers Guild Awards on...

In Texas, the Old, Kinder, Gentler G.O.P. Faces Its Alamo Moment

On the morning of Feb. 17, the opening day of early voting in the Texas primary elections, Senator John Cornyn...

Trump warns US will strike Iran with ‘force that has never been seen before’ if regime carries out ‘devastating’ attack

President Trump warned that the US would strike Iran with a “force that has never been seen before” if the regime...

After Producers Guild Awards, Can ‘One Battle After Another’ Be Beaten?

The Producers Guild of America awarded its top prize to “One Battle After Another” on Saturday night, extending an awards-season...

Gen Z Is Taking Over America’s Retirement Home

MovingPlace, from what I can tell, is to finding a moving company to haul your junk from one home to...

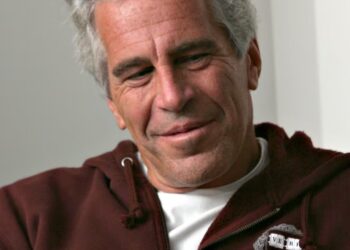

Epstein’s Creepy Medical Cabal Unmasked in DOJ Files Bombshell

A newly surfaced image from the millions of recently released Epstein files horrifyingly depicts a surgery being performed in the...

Photos show damage to major cities and tourist hotspots across the Middle East, from Dubai to Tehran

A yacht sails past a plume of smoke rising from the port of Jebel Ali, in southern Dubai. Fadel SENNA...

Iran Got Trump All Wrong

For decades, Iran managed to bluff American presidents. It deterred attacks from a superpower and carried out proxy campaigns against...