In praise of the mixtape and what music does so well — letting us be ourselves

I distinctly remember being on the family Mac in Brasília at 13 years old, grooving to a CD I’d just...

Trump’s FBI ‘podcasters’ face withering criticism for Brown shooting case screw ups

Authorities released a person of interest who had been detained over the weekend in connection with a deadly shooting at...

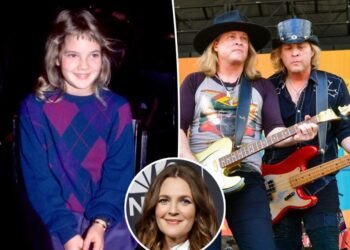

Nelson twins recall jumping in to help a young Drew Barrymore from ‘creepy guys’

Showbiz dynasties look out for one another, it seems. The brothers from the band Nelson — the sons of rock...

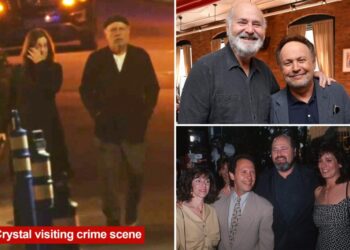

Billy Crystal seen at Rob Reiner’s home hours after his longtime friend’s death: ‘Looked like he was about to cry’

Actor Billy Crystal was spotted emotionally leaving the home of their longtime friend Rob Reiner hours after the famed filmmaker...

The Magnificent 7 isn’t that magnificent: 5 of the stocks have underperformed the market this year

S&P 500 futures were up 0.44% this morning after the index lost 1.07% on Friday, a day after setting a...

America cannot control China’s economic outcomes

China was shifting away from an export-dominated economy before the United States first imposed tariffs seven years ago. Yet a...

The CEO of Elanco has 6 kids. This is the career advice he gives them.

Elanco cuts hundreds of jobs Paul Morigi/Getty Images for SemaforElanco CEO Jeff Simmons said he urges his six kids to...

To China He Was a Master Villain. To Supporters He Was Their Hope.

Judges in Hong Kong delivered guilty verdicts in the landmark national security trial of the media tycoon and pro-democracy activist...

Work Advice: Karla’s final performance review, part 2

For those who missed the news, I’m stepping down as The Post’s Work Advice columnist after 14 years. For my...

‘The Emperor’s New Groove’ at 25: Kronk’s Enduring Appeal

“He’s a meme factory!” David Reynolds, the screenwriter behind “The Emperor’s New Groove,” said about Kronk, the good-hearted himbo henchman...