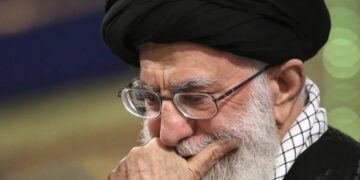

The supreme leader is dead. How succession works in Iran

DUBAI — The death of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei after almost 37 years in power raises paramount questions about the...

MAGA-Coded CBS Anchor Goes Full Trump on Iran War

Tony Dokoupil opened his special edition of CBS Evening News sounding more like a White House surrogate than a network...

Aries, March 2026: Your Monthly Horoscope

March is deeply Mars-coded, which is funny, because that’s your planet. The catch? Mars leaves your sign’s usual comfort zone...

I’m a senior software engineer laid off from Block. There are 3 things I’m keeping in mind as I reenter the job market.

Isaac Casanova, a senior software engineer laid off from Block, shares how he's navigating a tougher job market. Isaac CasanovaA...

The C.I.A. Helped Pinpoint a Gathering of Iranian Leaders. Then Israel Struck.

Shortly before the United States and Israel were poised to launch an attack on Iran, the C.I.A. zeroed in on...

The Man Who Destroyed Iran

In June 1989, when Ali Khamenei was elevated to the position of supreme leader of Iran, he let slip the...

Sierra Canyon’s domination in boys basketball continues with Open Division title

There are All-Star teams. Then there’s Sierra Canyon’s boys’ basketball team, made up of two McDonald’s All-Americans, a former Trinity...

In Ukraine, a Community of ‘Simple Believers’ Shuns the Modern World

On the outskirts of Kosmyryn, a village in western Ukraine, several men poured the foundation for a house. They used...

Weekly Horoscope: March 1-March 7

The energy feels different this week. A Full Moon eclipse in Virgo rips the lid off whatever you’ve been avoiding...

CNN Anchor Corners MAGA Senator on Trump’s Peace Lies

MAGA Sen. Rick Scott resorted to a contorted response after CNN anchor Jake Tapper cornered him on President Donald Trump’s...