This personal reflection is part of a series called Turning Points, in which writers explore what critical moments from this year might mean for the year ahead. You can read more by visiting the Turning Points series page.

Turning Point: In January, Donald Trump was sworn in for his second term, shaking the world and emboldening anti-democratic leaders.

Last year, I was forced into retirement.

Age was not the issue — I was only 43, with a long and promising career ahead.

Nor was it an inability to perform. Far from it: I had just led Thailand’s Move Forward Party to victory in the country’s 2023 elections. We won more than 14 million out of nearly 40 million votes amid a record 75.2 percent turnout, a feat that should have positioned me to become the country’s next prime minister.

But on Aug. 7, 2024, Thailand’s Constitutional Court dissolved the Move Forward Party. The judges, appointed directly or indirectly by the country’s military junta, also banned me from politics for 10 years. Just like that, I went from being prime minister in waiting to deposed parliamentarian. My democratic mandate had been overturned by institutions engineered to suppress democracy, in blatant disregard of the voters’ will.

Displaced and dejected, I returned to a place I once called home: the Harvard Kennedy School. This time, I arrived not as an ambitious and wide-eyed graduate student, but as a seasoned and battered research fellow. The irony was sharp: After being disqualified at home, I found myself requalified abroad, speaking about the new tricks authoritarian governments employ to hold onto power, and working to equip the next generation of leaders for a rapidly changing world.

This detour into academia has given me a closer view of what I have been sensing for some time: Democracies everywhere — not just in Thailand — are under strain. I have compared notes with reformers, policymakers and scholars from all corners of the globe — Bangladesh, Venezuela, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Tunisia, South Korea and the United States. Our histories may differ, but the lessons remain the same: Democracy is never self-sustaining. It demands constant vigilance; its guardrails can crumble faster than most citizens realize.

Last November, I joined Kennedy School students on election night to watch history unfold. I had been here before, in 2008, watching a young Black senator named Barack Obama win the presidency, convinced I was witnessing the dawn of a new democratic era. Sixteen years later, I stood in the same room, now as a former candidate for prime minister bearing the scars of a hard-fought campaign, watching the re-election of President Donald Trump. The venue was unchanged, but the political landscape and my own circumstances were unrecognizable.

What began that night was not merely a new chapter in American politics, but the opening act of a new world order where alliances shift, global norms morph and the certainties that have shaped the international community in the past century can no longer be assumed. Across the world, geopolitical hot spots are flaring. The Russia-Ukraine war grinds on; the Israel-Hamas conflict reshapes alliances; tensions between India and Pakistan simmer. Each sends ripples into Thailand. Cambodia-Thailand disputes have reached their most volatile point in more than a decade, a reminder that, in this part of the world — just like elsewhere — stability can abruptly splinter.

In 2026, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, known as ASEAN, will be thrust into a high-voltage moment. Old problems still fester, while new challenges emerge at breakneck speed — all amid the backdrop of an intensifying rivalry between the United States and China. Both global powers have the means and the will to pull Southeast Asia into their competing orbits, raising the risk that ASEAN could become an arena for a great-power contest with external agendas, rather than a driver of its own destiny.

In this political climate, the Southeast Asian tradition of “neutrality” — a diplomatic posture of indifference or refusal to take sides — may no longer suffice. States that treat neutrality as a passive shield could find it quickly pierced by major powers. Instead, when neutrality is an active pursuit, we gain the ability to navigate pressure from multiple directions without surrendering autonomy.

States that practice neutrality as a deliberate strategic craft are more likely to extract concessions without surrendering sovereignty, balance asymmetric relationships without losing agency and steer clear of unwanted compromises. In today’s era of intensifying great-power rivalry, I believe this skill must extend beyond the national to the collective. ASEAN’s ability to act as a coherent bloc will determine whether its neutrality translates into genuine bargaining power or, conversely, leaves its members fractured into isolated and vulnerable states.

Foreign policy is a reflection of domestic politics. Southeast Asian ballots and constitutions are layered with a complex web of militaries and political dynasties. If my own political journey has revealed anything, it is that our region is too often led by heirs of power rather than by pioneers of reform. These dynasties may preserve their family names, but they have left ASEAN brittle in a world that demands agility. My hope is that the next generation of leaders will either rise to the challenges that lie ahead or will step aside; democracy cannot wait.

I envision a future where the next generation of leaders across ASEAN rise together, united not by privilege, but by purpose. Their task will be to revive our region’s promise: to transform diversity into strength, crisis into competitiveness and aspirations into concrete progress. If we can nurture these voices and give them the pathways to lead, ASEAN can move beyond the weight of dynasties and divisions and truly claim its place as a resilient, united force in the world.

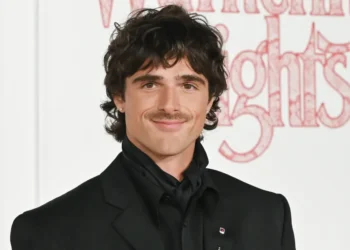

Pita Limjaroenrat, a former Thai politician, is a visiting fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

The post The World Order Is Shifting. Will Democracy Catch Up? appeared first on New York Times.