Israel seeks Iran’s decapitation while U.S. hits military targets as report says Supreme Leader Khamenei was killed

The U.S. and Israel are carrying out a two-part strategy against Iran that has reportedly resulted in the death of...

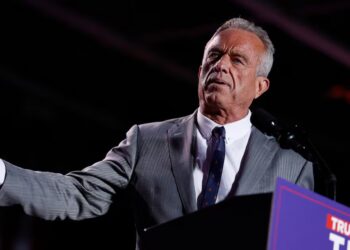

RFK Jr. Pleads With Rogan to Keep Backing Trump

Health and Human Services Secretary and MAHA architect Robert F. Kennedy Jr. kissed the Republican ring while appearing on The...

Bill Clinton Breaks Silence Following Epstein Grilling

Bill Clinton is finally talking Epstein—and he’s insisting there’s nothing to see here. The former president broke his silence after...

Trump’s war with Iran, briefly explained

This story appeared in The Logoff, a daily newsletter that helps you stay informed about the Trump administration without letting...

Worms in food, poor medical care, lights on 24/7: Families tell of life in Texas detention center

LAREDO, Texas — A month after ICE agents sent the young Ecuadoran mother and her 7-year-old daughter to a sprawling detention center...

André 3000 Breaks Down How He Chooses Which Songs To Record Guest Verses

Anytime there’s a guest verse from André 3000, it becomes an event in hip-hop instantly. He’s made a significant portion...

The US shared a new video of its strikes on Iran showing it launching missiles and blowing up targets

US Central Command shared footage of strikes on Iranian targets. US Central Command/XThe US shared new video footage from its...

LAPD on high alert after US strikes on Iran

The Los Angeles Police Department will increase patrols around the city after the US and Israel launched airstrikes against Iran...

Lab-Grown Brains Growing More Powerful

Back in 1907, American biologist Henry Van Peters Wilson discovered that sponges will re-form into living creatures after their cells...

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khameini confirmed dead after US-Israel strikes: reports

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayotollah Ali Khameini, was confirmed dead on Saturday after the U.S. and Israelcoordinated attacks against the country,...