Dubai’s worst nightmare unfolds as Iran strikes Gulf neighbors

Dubai’s nightmare scenario unfolded Saturday: Defense systems repelling Iranian missiles and drones over its famous skyscrapers, random explosions and plumes...

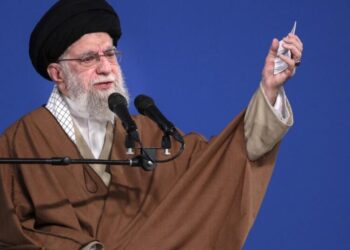

Live updates Iran’s supreme leader killed during U.S.-Israeli attack, Trump says

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader since 1989, was killed, President Donald Trump said Saturday, after the United States and...

Republicans face a ‘major test of loyalty’ after Trump’s latest ‘slap in the face’

Republicans in Congress will return next week to face a “major test of loyalty” after President Donald Trump’s most recent...

Iran attacks US military base in Saudi Arabia with surge of ballistic missiles

A US military base in Saudi Arabia is under attack, being bombarded by Iranian ballistic missiles, according to Fox News. ...

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, is dead at 86

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Shiite Muslim cleric who played a behind-the-scenes role in Iran’s Islamic revolution, served two terms as...

Iran’s Supreme Leader Killed in U.S.-Israeli Attacks

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was killed on Saturday in the opening salvo of a major military campaign launched...

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who ruled Iran with iron grip and defied the West, killed in strike

BEIRUT — Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Hosseini Khamenei, who was killed in the U.S.-Israeli attack on Iran on Saturday, had over more...

How the BAFTAs Bungled Its Big Awards Night

As the BAFTA movie awards were about to begin this past Sunday in London, the floor manager gave a special...

‘Peace President’ Trump Boasts He Will Bomb For Days to Come

Donald Trump took to Truth Social late Saturday to declare Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei dead and boast of Iran...

Trump says Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei was killed during strikes on Iran

Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, led the country for nearly four decades until his death in late February. AHMAD...