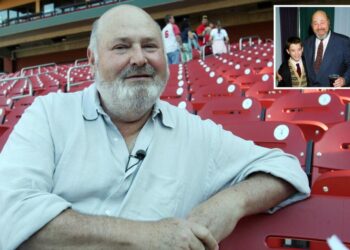

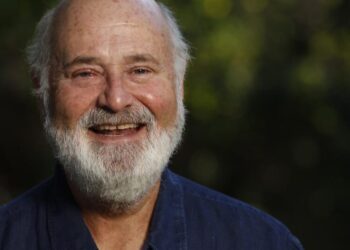

Tributes to Rob Reiner pour in from Hollywood and beyond: ‘The reason I became an actor’

The entertainment industry — and beyond — was left reeling after legendary director Rob Reiner and his wife were found...

The ‘Troublemaker’ Who Took On China Faces Up to Life in Jail After Guilty Verdicts

Judges in Hong Kong delivered guilty verdicts in the landmark national security trial of the media tycoon and pro-democracy activist...

Conservative Wins Resoundingly in Chile’s Presidential Election

José Antonio Kast, a conservative candidate, was elected Chile’s president on Sunday, a sharp rightward swing for a country where...

China Nears First Investment Decline in 3 Decades After Sharp Monthly Drop

Investment in China slowed drastically in November, propelling the country closer toward its first annual decline in more than three...

‘There’s Still Hope.’ How the Bondi Community Rushed to Help.

Scrolling through the videos and photos from the shooting in Bondi Beach, not far from where I lived in Sydney,...

Family of ‘Hero’ Australian Bystander Who Disarmed Gunman Speaks Out

More details surrounding the man hailed a “hero” for tackling and disarming a gunman in the Bondi Beach shootings have...

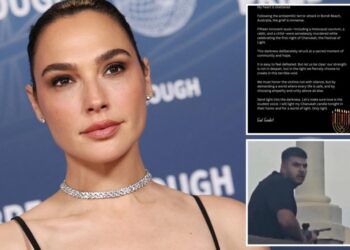

Gal Gadot ‘shattered’ as stars condemn deadly Bondi Beach terror attack at Hanukkah celebration

Hollywood stars, including Gal Gadot, Ashton Kutcher and Rebel Wilson, reacted to the mass shooting during a Hanukkah celebration Sunday...

Rob Reiner used his fame to advocate for progressive causes. ‘Just a really special man. A terrible day’

Rob Reiner was known to millions as a TV actor and film director. But the Brentwood resident, known for the...

‘Emily in Paris,’ Plus 10 Things to Watch on TV This Week

Between streaming and cable, viewers have a seemingly endless variety of things to watch. Here is a selection of TV...

Jacob Cofie meets Eric Musselman’s challenge, leading USC past Washington State

Before Sunday’s game against Washington State, USC coach Eric Musselman told Jacob Cofie to be aggressive and look for his...