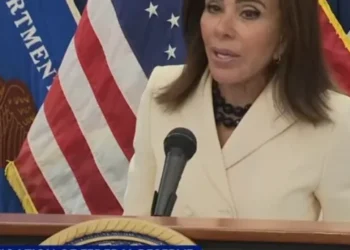

Jeanine Pirro flooded with mockery after furious press conference: ‘Not taking it well!’

Reactions rolled in on Friday after Jeanine Pirro, U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, held an unusual press conference...

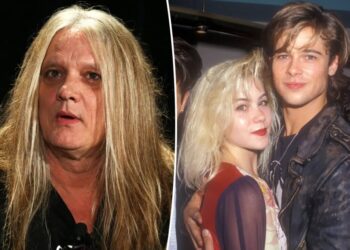

Sebastian Bach breaks silence on Christina Applegate and Brad Pitt love triangle

Sebastian Bach is apologizing for stepping out with Christina Applegate while she was dating Brad Pitt. “ was very surprised...

Is the Cure for Peanut Allergies Hiding in Your Spit?

According to a new study published in Cell Host & Microbe by researchers at McMaster University, certain bacteria found in...

Best movies of the year, ranked by fans, revealed ahead of Oscars 2026

Ahead of the 2026 Oscars this Sunday, Rotten Tomatoes has revealed the most popular movies of the past year —...

UCLA stuns Michigan State to advance to Big Ten tournament semifinals

CHICAGO — When UCLA met Michigan State on its home court less than a month ago, it turned out to be an...

‘Baywatch’ boot camp bring stars’ sizzling bods to Venice Beach ahead of reboot

Stars of the new “Baywatch” reboot showed off their beach bods while taking part in an intense training session on...

Psycho teen accused of fatally stabbing ICU nurse in random attack tells cops he ‘wanted to kill someone’ for a long time

A psycho Massachusetts teen accused of fatally stabbing a sleeping ICU nurse after breaking into her home allegedly told cops...

‘We Are the Shaggs’ Review: The Band Is Awful, but the Movie Isn’t

Several decades ago, I used to get a big kick out of subjecting unsuspecting visitors to a record by an...

California traveler accused of attacking TSA officers, seriously injuring Dallas cop at airport

A California man was federally charged after allegedly attacking two Transportation Security Administration (TSA) officers and seriously injuring a Dallas...

Rep. Jasmine Crockett’s fugitive security guard killed in standoff with Dallas SWAT team: report

A Texas fugitive who allegedly worked as a security guard for Rep. Jasmine Crockett (D-Texas) was killed in a standoff...