Kelly Osbourne wows at 2026 BRIT Awards with mom Sharon after fiercely defending her slim figure

Kelly Osbourne showed off her dramatic weight loss while walking the red carpet with her mom, Sharon, at the 2026...

No more whining — Trump and Israel are busy saving the world from Iran

For years, gutless bureaucrats in Europe and at the United Nations have been begging Iran’s ayatollahs to play nice. They...

“The Worst-Case Outcome Is Complete Chaos”

In the final hours before U.S. warplanes bombarded Iran on Saturday, President Trump wanted to go over the plan one...

Will Trump’s Iran strikes end the regime — or put more time on the clock?

For more than 45 years, U.S. presidents have wanted to destroy the radical, anti-American regime in Tehran. They always concluded...

‘Handmaid’s Tale’ alum Ever Carradine details ‘hardest week of my life’ after dad Robert’s tragic death

Ever Carradine is reflecting on “one of the hardest weeks” of her entire life following the tragic passing of her...

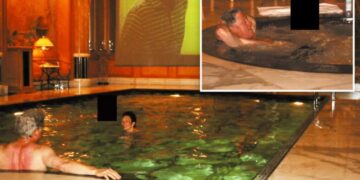

Trump bashed for using Mar-a-Lago ‘blanket fort’ to monitor Iran strikes

President Donald Trump was bashed on Saturday after photos emerged of the “blanket fort” at his Mar-a-Lago estate that he...

Thanks to President Trump, the hour of Iran’s freedom is at hand

Reza Pahlavi is a leader of the Iranian democratic opposition. He is the eldest son of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the...

Iran’s missile barrage tests whether U.S. has enough interceptors

The ability of the US, Israel and Gulf Arab states to weather Iran’s retaliatory strikes will depend on how many...

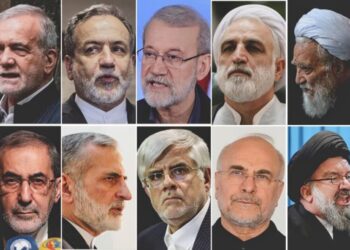

A look at Iran’s key political and religious figures

The U.S. and Israel launched a major attack on Iran on Saturday, and President Trump called on the Iranian public...

The Immovable and Ruinous Obsessions of Ayatollah Khamenei

In June 1989, when Ali Khamenei was elevated to the position of supreme leader of Iran, he let slip the...