Mel B marries hairstylist Rory McPhee at star-studded London wedding, including Spice Girl Emma Bunton

When two become one. Spice Girls singer Mel B and hairstylist Rory McPhee said “I do” Saturday in London. The...

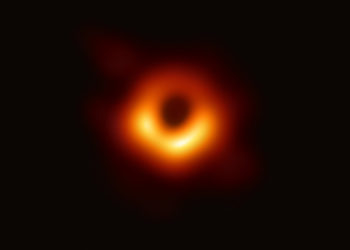

Astronomers discovered a whole new class of black holes

Scientists have observed a new type of black hole that is too heavy to have been born from a star...

The Eternal Die team always knew Lost In Random would make a great roguelike

While 2021’s Lost in Random was far from a roguelike, the team behind the adventure game always knew its zany...

Been Waiting Forever To Buy a Sonos Arc? Well, Now It’s $300 Off.

Yes, yes. This is the old model. Before you zip away to the X in the corner of your browser...

‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ Evolves July 4th To Post Covid $26M+ Record; 5-Day Opening Now Roaring To $141M+

SATURDAY AM UPDATE: Barbeques, swimming pools and fireworks couldn’t keep these dinosaurs away as Universal & Amblin‘s Jurassic World Rebirth...

Lawsuit from mom of man killed by Seattle officer involved in multiple deaths is moving forward

Six years after her son was killed by a Seattle police officer involved in multiple deadly encounters, a federal judge...

Trump administration deports 8 migrants to South Sudan

The Trump administration deported eight migrants to South Sudan, according to a Department of Homeland Security official, after the administration...

Florida beachgoers injured by lightning strike on Fourth of July

An outing on the Fourth of July turned tragic along Florida’s Gulf Coast, as first responders reported three people sought medical...

FDA Issues Most-Serious Risk Warning for Cucumber Recall

The federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has classified a series of recalls for cucumber featuring products, all produced by...

Supporters of banned Palestine Action group arrested at London protest

Police have arrested protesters in London for supporting activist group Palestine Action, which was banned at midnight in the United...