Mystery deepens as body discovered during search for missing American in island paradise

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles! Police in the Turks and Caicos Islands have discovered the body of...

BRICS group condemns increase of tariffs in summit overshadowed by Middle East tensions

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — The BRICS bloc of developing nations on Sunday condemned the increase of tariffs and attacks...

Appreciation: Friends bid farewell to Rolando ‘Veloz’ Gonzalez, an L.A. Spanish-language radio pioneer

The Los Angeles sports world mourned the loss of one of its most beloved voices, Rolando “El Veloz” Gonzalez, the...

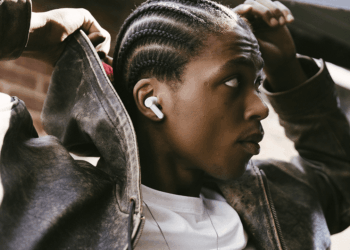

Cambridge Audio Launches ‘Melomania A100’ High-Fidelity Earbuds

Cambridge Audio has launched the Melomania A100, its most feature-packed set of earbuds yet. The brand – a favorite among...

Texas floods: Death toll hits 70, 11 campers remain missing

KERRVILLE, Texas (AP) — Families sifted through waterlogged debris Sunday and stepped inside empty cabins at Camp Mystic, an all-girls summer...

Dodgers Predicted to Replace Max Muncy With $70M All-Star in Blockbuster Trade

The Los Angeles Dodgers got some bad news at third base just as it seemed their veteran starter was turning...

Go woke, go MEGA broke — this luxury company’s sales just plummeted 97%

2025’s Pride Month went out with a glorious whimper. Many didn’t even notice it happened at all. Compared to previous...

Martin Brundle and Jeremy Clarkson Share Hilarious Grid Walk Moment at British GP

Ahead of the British Grand Prix, Sky Sports commentator Martin Brundle had a funny exchange with Top Gear’s Jeremy Clarkson....

The Echo Spot Is Available for Its Cheapest Price Ever

I’m not asking for much from my smart devices. Not every one of them needs to be a big, old...

Couple killed in wine cellar mishap with dry ice as they prep for July 4 bash : reports

A Texas couple preparing for an Independence Day party was found dead in their wine cellar after being knocked out...