WWE Elimination Chamber: Danhausen Unveiled as the Crate Mystery (And He Got Booed)

After a month of teasing a mysterious crate, WWE finally unveiled what was inside at Elimination Chamber. Fans were sure...

Trump Rolls the Iron Dice

No tears should flow for the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, or for his associated butchers in the...

Iranians Take to the Streets to Celebrate Khamenei’s Death

Large crowds of Iranians poured into the streets of Tehran and other cities across Iran overnight, celebrating the news that...

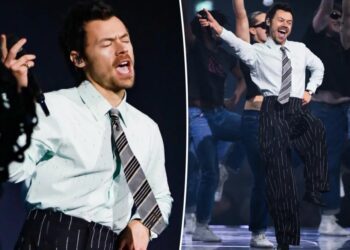

Harry Styles opens 2026 BRIT Awards with show-stopping performance of ‘Aperture’

Harry Styles opened the 2026 BRIT Awards with a captivating performance of his song, “Aperture,” which is featured on his...

Multiple members of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s family killed in US-Israeli strikes on Iran

Multiple members of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s family — including his daughter and grandchild — were killed when the...

Kim Kardashian fully transforms into Las Vegas showgirl on ‘The Fifth Wheel’ set

Kim Kardashian was spotted fully blinged out on the set of her new movie this week. The “Kardashians” star was...

Why Trump’s War Is Only About Himself: Wolff

President Donald Trump’s unauthorized war in Iran is doomed to bring chaos and anarchy, not positive change, his biographer claims....

1 dead, at least 20 injured in Israel after Iranian missile hits Tel Aviv

An Israeli woman died and at least 20 others were injured after an Iranian ballistic missile slammed into Tel Aviv...

Expert flags ‘most troubling’ part of Trump’s latest ‘campaign’ in Iran

A military expert flagged the “most troubling” part of President Donald Trump’s decision to coordinate an attack on Iran with...

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Hard-Line Cleric Who Made Iran a Regional Power, Dies at 86

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who in more than three decades as Iran’s supreme leader turned the Islamic Republic into a regional...