EXCLUSIVE: David Oyelowo says he wants to use his star power to make more films in Africa and help boost the continent’s movie-making prowess. But he assures “there’s not going to be a cultural colonialism” insisting that the move has got to “benefit people on the ground.”

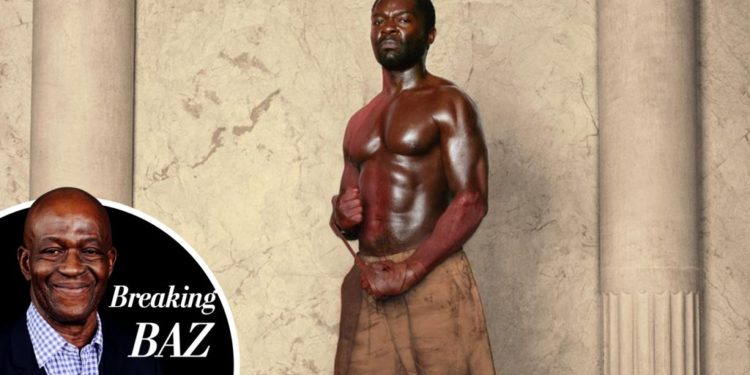

The actor met with Deadline during a break from rehearsals and previews of a new production of Shakespeare‘s blistering and bloodthirsty play Coriolanus at London’s National Theatre with the Lawmen: Bass Reeves actor playing the titular role of the noble, patrician, war hero Caius Martius Coriolanus, who discovers to his cost that heroics on the battlefield do not readily equip him for the vicious blood sports of politics in Ancient Rome. The powerful play, directed by Olivier Award winner Lyndsey Turner, has its official opening night on September 24.

Oyelowo, who was born in Oxford, England to Nigerian parents, is well aware of the arguments about Hollywood savior types going into African regions to take advantage of resources and giving little back in return.

Watch on Deadline

“It can’t just be us going in and mining it for all of that richness and extricating. It’s got to be a benefit; to put something on the ground there in the same way that I can’t just bring all of my American crew to the U.K. to make a film. There are infrastructures in place that mean: No, no, no, if you’re going to be here, you have to use our people. And that then benefits the country, that’s what elicits tax breaks and things like that,” he tells us.

The thespian says that he admires what his friend Idris Elba has been doing in Africa and reveals that he and the Hijack star have been talking about ways in which to cultivate filming in Africa “both individually and together,” although he stresses that he and Elba have no plans to link up and create a studio.

Rather, he notes, “it’s just about finding projects that enable us to build infrastructure.”

He has more than a concept of a plan already in place.

For some time, he and Ngozi Onwurah, who directed Oyelowo, David Gysin, Nikki Amaka-Bird and Sharon Duncan-Brewster in the BAFTA-winning 2006 BBC film drama Shoot the Messenger, and acclaimed writer Bola Agbaje (Gone Too Far), have been developing a project with the BBC about the Biafran War called Biafra.

The project is the story of what happened in Nigeria during the 1967-70 conflict that tore the West African country apart. Oyelowo says that the drama will be explored “through the eyes of fictional characters… obviously we are still living with a legacy in ways that people probably don’t even realize.”

He confirmed that Ngozi will direct him in the drama. Oyelowo is producing through the Yoruba Saxon Productions company he founded with his wife Jessica Oyelowo. Yvonne Isimeme Izabazebo (Rye Lane) is also an executive producer.

Oyelowo says that he loved making Miranda Nair’s 2016 film Queen of Katwe with Lupita Nyong’o and Madina Nalwanga on location in Uganda and South Africa; the year before, filmmaker Amma Asante shot parts of her beautiful movie A United Kingdom in Botswana with Oyelowo and Rosamund Pike.

There are other projects “in the hopper, developmentally,” as he puts it, that are also partly set in Africa, while also observing that “obviously, my prejudices are towards Nigeria.”

Oyelowo boasts that the continent “is just teeming with poetry and vibrancy and history” but it pains him that “we are just not seeing productions on screen in a way that is commensurate with the epic scale of what the African continent has to offer.”

Citing the phenomenal success of shows like Squid Game and Shogun, Oyelowo believes that through the “democratization that streaming brings,” there’s “just no excuse to not seeing those stories that may not be culturally what we are used to, but bring a freshness of perspective to a continent.”

There are plenty of ideas around, he says, that he believes “are going to be exciting for a global audience.”

Although Lawmen: Bass Reeves was shot in Texas and is an American story, as it were, I see his point when he notes that for years he was told that the limited series “would not have a global audience and yet it went on to be the most watched show globally on Paramount+ last year.”

Oyelowo agrees that parts of Africa lack the technical might of Hollywood and London, but suggests that the infrastructure is there, it just “needs development.”

And the way to do that, he reasons, is to go there and “cultivate it.” That will mean having to take some production equipment there initially “and then less and less and less. But you just have to point a camera in that environment and you have scale and scope and vibrancy, and all the things that you’re looking for from a cinematic perspective.”

Using football, okay soccer, as an analogy he says “if you value your football team, you’ll go and scout for what the future of that football team should look like, and you’ll start cultivating those players before anyone knows about them. That’s because you value that football team. And I value that continent.”

For now though, foremost on his mind is getting to grips with the “muddy murkiness” of political shenanigans in ancient Rome for Coriolanus at the National’s 1,150-seat Olivier theatre auditorium.

It’s a grand-scale production with sets by Es Devlin. She and Lyndsey Turner staged Hamlet, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, at London’s Barbican Theatre in 2015. Oyelowo admires that production for making Shakespeare accessible to audiences who weren’t necessarily wildly conversant with the Bard’s oeuvre.

He began discussing plans with Turner of taking on the tragedy of Coriolanus, and National Theatre artistic director Rufus Norris invited them to mount a production in the Olivier.

Oyelowo’s well acquainted with the timeless drama underpinned by “a giant war” with ruthless politics at its center. He admits that he and Turner “very much selected 2024 as the year to do it because Britain just had a general election [although it was only called in May and held in July, a UK general election had been expected this year] and America, of course, is in the middle of a presidential election taking place in an unprecedented political landscape.”

What Coriolanus “hits on so brilliantly,” he says, and is “very relevant to today” is the fact that “we are continuing inexorably seemingly to cascade into a politics of personality over policies.”

Stroking his hair in a mock coquettish manner, he says it’s like, “Is she beautiful? Is he annoying? Is he presidential? Is he handsome? Is she confidence-inducing? As opposed to what are they actually going to do and what do they stand for?”

It’s all geared to and rooted in personality, he attests.

“And in many ways, Coriolanus’ personality is what people are constantly using to weaponize against him as opposed to his policies, which are what he constantly wants to talk about,” he says while agreeing that “everyone says he’s arrogant, he’s prideful – there is righteous indignation to him. There’s a humility tied to his desire to not be aggrandized.”

Coriolanus is not a friend of the people. He’s a soldier – a valiant and brilliant warrior who refuses to be a political poster boy.

Away from the field of war, he wants to be useful now that he’s home. He has ideas and that becomes problematic.

The self-interested senate warns him that he can’t gain power and then try and elicit change. As with Washington and Westminster, it’s a world of lobbyists, middlemen, and women, and agitators that, as Oyelowo says, “leaves a mess on your hands.”

It’s that “muddiness and murkiness” that the actor craves because that’s where the heart of the drama lies.

Oyelowo and I, both hail from ancient Nigerian royal and noble families — I might argue that my bloodline boasts more royal blood than his, but that’s a discussion for another day. I mention it to him because it has always struck me that Coriolanus, whatever his faults, is, as was someone like John McCain, a man of honor.

The actor sees my point and says that he too sees that connection to the play. “Being Nigerian, having lived there for a number of years, of being from a royal family in Nigeria, and that sense of nobility, that sense of self, that sense of how you carry yourself being something that can be both admired and vilified. And it’s something that has a different sensibility in a British context, in an American context.”

One of the reasons he’s so keen on performing the play is because “post Second World War, I feel like Shakespeare’s Roman plays, the History plays, have all gone through this lens of stiff upper lip kind of British class system combined with the kind of actor that gets to play these roles.”

When he was being classically trained 26, or more, years ago at the London Academy of Music & Dramatic Art, he reveals that “I was the only Black student in my entire year, but also the entire school.”

That clearly tells you, he says, “the demographic of person who was getting to play this kind of role. And that of course goes into what the role is perceived to be. Now, you add the notion of nobility, the notion of politics, the notion of post-monarch — Rome was a republic then, essentially, all of that is going through a British upper-middle-class lens in terms of what we’re seeing again, and again, and again.”

Banging the little table in an office at the National’s Southbank complex, he says: “But this was Rome! These are Italians. This is Shakespeare writing 400 years ago about events that happened several centuries before his time. And so I personally feel that there are as many different ways to look at this play that are outside of that.

“Of course, we are here on the Southbank in London, but I bring my sense of what nobility looks like, and that’s to do with being Nigerian, being American and being British. And I think it just has a different energy,” he says adding that those aforementioned topics have “been the driver of my conversations with Lyndsey over the years coming into doing the play.”

He first performed it in a student production directed by Spencer Hinton at the Edinburgh Festival. However, back then he played the part of the Volscian general Tullus Aufidius, Coriolanus’s arch rival. However, the two warriors find a strange kinship until it’s shattered.

Oyelowo jokes that at one performance up in Scotland, the traveling troupe played to an audience of two. “It was a seminal moment of my career,” he says.

That’s when he became fascinated with the play and with Shakespeare.

When Oyelowo was with the Royal Shakespeare Company, director Michael Boyd took a punt and gave him the title role in his celebrated production of Henry VI “I will forever love him for that gift,” says the actor for what Boyd taught him about performing Shakespeare with clarity.

Years later, in 2016, Oyelowo played Othello in director Sam Gold’s scintillating production at New York Theatre Workshop, which starred Daniel Craig as Iago.

There has been much chatter over the years of the possibility of that production, of which Barbara Broccoli was a producer, being filmed. “That’s definitely an ambition,” Oyelowo confirms.

Then he laughs and says, “but I have so many ambitions and they all take so long to come to fruition but they’re very satisfying when they do. Sam Gold just did an incredible job with that and it lends itself to a film and as to whether Daniel would still be involved, we’ll see.”

Seeking more information, he flatly tells me: “I don’t know. But count me in if they all say yes.”

A matter that has been settled, is that Coriolanus at the National will be captured by NT Live’s cameras, although, for now, there are no details about when the filmed NT Live performance will be shown in theaters.

Next up for Oyelowo is a comedy series he starred in for Apple TV+ called Government Cheese. He shot the Paul Hunter and Aeysha Carr script in LA for six months ahead of traveling to London to rehearse Coriolanus, which also stars Kobna Holbrook-Smith, Sam Hazeldine, Pamela Nomvete, Peter Forbes, Jo Stone-Fewings, Jordan Metcalf and Kemi-Bo Jacobs.

Coriolanus runs at the National until November 9.

The post Breaking Baz: ‘Lawmen: Bass Reeves’ Star David Oyelowo Back On Stage In London Playing ‘Coriolanus’, Says He Wants To Boost Filmmaking In Africa appeared first on Deadline.