NJ-based shipping company slams Iran’s ‘barbaric attack’ on oil tanker that killed 1 crew member

The crew of a US-owned oil tanker found themselves “fighting for their lives” earlier this week, after a “barbaric attack”...

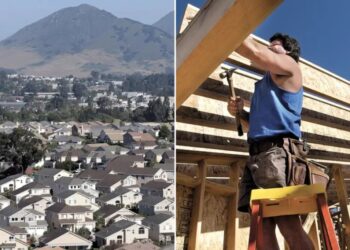

Trump Issues Executive Orders to Tackle Housing Supply, Demand

President Trump on Friday released two executive orders aimed at tackling the nation’s housing crisis, a day after the Senate...

Sydney Douglas leads Corona Centennial to Division I girls’ basketball state title

SACRAMENTO — When 6-foot-7 Sydney Douglas returned from a finger injury just before the postseason began after missing 11 games, Corona Centennial...

Build affordable housing, pay a price

San Luis Obispo has a housing problem. Anyone who’s tried to rent or buy there lately already knows it. The...

Jim Jordan confronted by Trump’s own words on CNN: ‘I’m not going to start a war’

CNN host Kasie Hunt and Rep. Jim Jordan engaged in a heated exchange Thursday on “The Arena” over Trump’s Iran...

Trump ignored top general’s Iran warnings: report

President Donald Trump was warned before launching military action against Iran that Tehran could try to shut down the vital...

Past presidents claimed Iran couldn’t have nuclear weapons — Trump is the only one to take action

Every past president since Bill Clinton, Republican and Democrat alike, has declared that Iran couldn’t be permitted to develop nuclear...

Judge Quashes Justice Dept.’s Subpoenas of Fed, Crippling Its Pursuit of Trump’s Rivals

A federal judge in Washington threw a major roadblock into a criminal investigation of Jerome H. Powell, the Federal Reserve...

Trump DOJ quietly quits case against flag-burning protester at White House

President Donald Trump’s Justice Department is dropping charges against a man who burned the American flag outside the White House...

This gung-ho Trump thug thinks he’s a bouncer — not a senator

Leadership is supposed to be calm, measured and disciplined. Apparently no one told U.S. Sen. Tim Sheehy (R-MT). Because what...