Astronauts Give Crucial Clue About NASA’s Emergency Space Evacuation

Four astronauts had to cut their mission on board the International Space Station short after a “medical concern” forced NASA...

Five Fronts in Trump’s Culture War

In his first term, President Trump took issue with some actors, arts funding and the media. In his second, he...

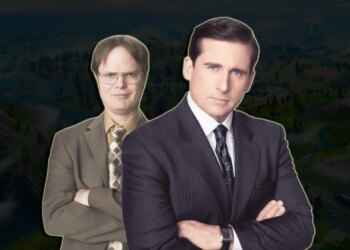

The Office Fortnite Skins Release Date Leaked – Bundle Items & Prices Revealed

The Office Fortnite collab release date has reportedly been leaked early online. According to dataminers, Michael Scott and Dwight Schrute...

Trump’s Displays Worst Bruising Yet—on His ‘Good’ Hand

President Donald Trump had bruising on both hands that was on full display while he led a signing ceremony for...

Trump Hit With Multiple Midterm Warnings in Brutal Poll

A damning poll has revealed President Donald Trump is recording dire approval ratings across the board, with voters believing the...

Kyle Gass Promises Epic Tenacious D Comeback After Healing Rift With Jack Black Over ‘Highly Inappropriate’ Joke

The longtime musical duo of Jack Black and Kyle Gass hit a roadblock in 2024 after Gass made an ill-advised...

I spent 10 weeks backpacking through South America. Here are the 4 places I’d visit again in a heartbeat.

I enjoyed hiking around Torres del Paine National Park. Isabel Vasquez LarsonIn 2022, I quit my job to backpack through...

How To Stay Safe and Warm In Extreme Cold Weather

Record cold temperatures are expected to hit parts of the United States this week. Arctic air amassing in northern Canada...

‘Like Water for Chocolate’ Director Says HBO Adaptation ‘Matured on Every Level’ in Final Episodes | Exclusive

“Like Water for Chocolate” is getting ready to unveil a cinematic-level Season 2, which director Julián de Tavira said stems...

‘He broke the law’: Jack Smith comes out swinging at Trump hearing

Former special counsel Jack Smith wasted no time declaring that President Donald Trump “broke the law” at a congressional hearing...