Death of Girl From Los Angeles School Investigated as a Homicide, Police Say

The Los Angeles police are investigating the death of a girl who attended Reseda High School as a homicide, a...

Dubai International Airport rocked by Iranian counterstrike following US-Israeli attacks

Dubai International Airport was struck during a counterstrike from the Islamic Republic Saturday, Emirati authorities have confirmed. Follow The Post’s...

Claude hits No. 1 on App Store as ChatGPT users defect in show of support for Anthropic’s Pentagon stance

Anthropic's Claude has seen an influx of users defecting from ChatGPT picture alliance/dpa/picture alliance via Getty ImagesAnthropic's stance against the...

Guess What Trump Values Above the Constitution

At several points during the State of the Union on Tuesday, Donald Trump lashed out against congressional Democrats with jeers...

Tom Hanks’ son Chet says he’s trapped in Colombia without his US passport, begs to be freed: ‘I’m an American citizen’

Tom Hanks’ son Chet Hanks is stranded in Colombia. “Ya’ll ready for story time?” Chet said in an Instagram video...

Oil Shipments in Persian Gulf Already Disrupted by Iran Attack

The widening military conflict in the Persian Gulf quickly began to disrupt shipping in one of the world’s biggest oil-and-gas...

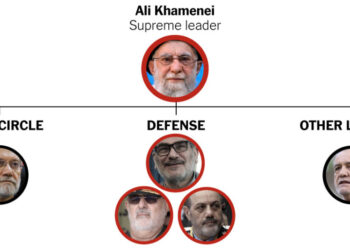

The Outlook Is Grim for a Freer Iran

Bombs are falling on Iran. The apparent goals of the strikes that began on Saturday, as pronounced by President Trump,...

US and Iranian Ambassadors square off at emergency meeting: ‘Be polite!’

The U.S. and Iranian Ambassadors to the United Nations squared off during an emergency meeting on Saturday. The U.N Security...

Trump Tells Iranians to ‘Take Over’ Their Government. But How?

As President Trump announced the opening strikes of a U.S.-led assault on Iran, he told the country’s soldiers to “lay...

Trump’s Decision to Strike Iran Opens New Fissures in Midterms

President Trump’s decision to attack Iran pushed a new, unpredictable issue to the forefront of American politics just as the...