How Alfred the service dog changes the rights of Lyft riders nationwide

The ride-sharing company Lyft will ensure the rights of blind and other disabled passengers across the country to travel with...

California national parks set attendance record, despite controversy

Despite morale-sapping staff layoffs, bizarre executive orders and a 43-day federal government shutdown last fall, the grandeur and serenity of...

Police Drones in Haiti Have Killed More Than 1,000 People

With all eyes on West Asia as the US and Israel unleash devastating air strikes on Iran, another deadly conflict...

NATO allies are linking their defenses together to better hunt and kill drones on its eastern edge

Digital Shield 2.0 is the second test in an ongoing exercise to strengthen air surveillance on Russia's border. US Army...

Kraft Heinz and the cost of narrow capitalism

Kraft Heinz has paused its proposed breakup, stepping back from dismantling the 2015 megamerger engineered by Warren Buffett and 3G...

My promise to you: AI didn’t write this column, and if it’s after my job, it’ll be over my dead body

For quite a while now, someone has been living inside my computer, writing emails for me. I don’t recall signing...

Trump demands TSA employees work unpaid – and issues ‘promise’ for those who do

Just hours after Transportation Security Administration (TSA) workers missed their first full paycheck amid the ongoing partial government shutdown, President...

I want another child, but my husband doesn’t. I’ve considered leaving, but instead, I’m looking for other ways to feel fulfilled.

The author wants a second child, but her husband doesn't. Courtesy of Claire VolkmanI want a second baby, but my...

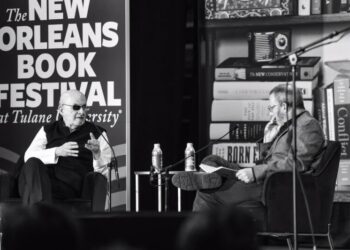

Salman Rushdie Doesn’t Want to Be Your ‘Free Speech Barbie’

“It’s a subject I’m anxious to change,” the author Salman Rushdie told the Atlantic staff writer George Packer at the...

Kids in hospital help penguins woo mates with painted pebbles

The penguins crowded around a green wheelbarrow, eager to see what was making the clattering noise inside. Moments later, more...