Trump’s Unilateral Attack on Iran Paves Way for Broader Dispute Over War Powers

President Trump’s unilateral decision to launch a major attack on Iran has opened a new chapter in a recurring debate...

Trump’s Iran strikes came at the behest of an ‘unusual pair’ of allies: report

President Donald Trumpmay have been led to strike Iran alongside Israel by an “unusual pair” of allies, a new report...

Netanyahu Takes His Shot at Regime Change in Iran

The joint U.S.-Israel attack on Iran is, in one sense, a long-held aspiration for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel....

San Francisco Ballet Pulls Out of Kennedy Center Performances

The San Francisco Ballet has withdrawn from a series of performances at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing...

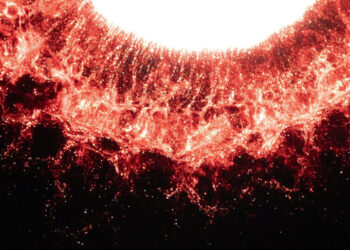

Reported airstrike hits Iranian girls’ school

BEIRUT — The U.S. military told The Washington Post it was “looking into” reports of an airstrike Saturday morning that...

Attacks Close Airspace in Middle East, Causing 1,600 Flight cancellations

After the U.S.-led attack on Iran, a wide corridor of airspace over the Middle East has been closed, with Israel,...

SoCal warship played pivotal role in deadly Iran strikes

The Southern California warship USS Abraham Lincoln played a critical role in the coordinated strikes against Iran early Saturday morning....

Only 21% of Americans Support the United States Initiating an Attack on Iran

Only 21% of Americans Support the United States Initiating an Attack on Iran Feb. 28, 2026 The public’s appetite for...

Shipping Traffic Through Strait of Hormuz Plummets After Attacks on Iran

Commercial ship traffic through the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow waterway on Iran’s southern border connecting the Persian Gulf to...

U.N. chief condemns U.S.-Israeli attacks on Iran at emergency Security Council meeting

UNITED NATIONS — The United Nations’ chief condemned the U.S.-Israeli airstrikes on Iran and called for an immediate return to negotiations “to...