‘Handmaid’s Tale’ alum Ever Carradine details ‘hardest week of my life’ after dad Robert’s tragic death

Ever Carradine is reflecting on “one of the hardest weeks” of her entire life following the tragic passing of her...

Trump bashed for using Mar-a-Lago ‘blanket fort’ to monitor Iran strikes

President Donald Trump was bashed on Saturday after photos emerged of the “blanket fort” at his Mar-a-Lago estate that he...

Thanks to President Trump, the hour of Iran’s freedom is at hand

Reza Pahlavi is a leader of the Iranian democratic opposition. He is the eldest son of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the...

Iran’s missile barrage tests whether U.S. has enough interceptors

The ability of the US, Israel and Gulf Arab states to weather Iran’s retaliatory strikes will depend on how many...

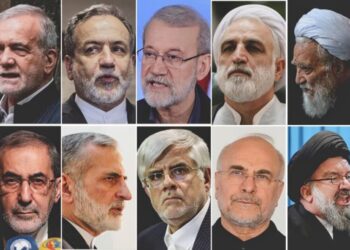

A look at Iran’s key political and religious figures

The U.S. and Israel launched a major attack on Iran on Saturday, and President Trump called on the Iranian public...

The Immovable and Ruinous Obsessions of Ayatollah Khamenei

In June 1989, when Ali Khamenei was elevated to the position of supreme leader of Iran, he let slip the...

Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader Who Built a De Facto Military Dictatorship, Killed in U.S.-Israeli Strikes

The years did not mellow Ali Khamenei. Appointed Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran at age 50, he...

OpenAI sweeps in to ink deal with Pentagon as Anthropic is designated a ‘supply chain risk’—an unprecedented action likely to crimp its growth

OpenAI announced late Friday it reached a dealfor the Pentagon to use its AI models in classified systems, just hours...

Ethiopian leader’s vision for nation includes an Eritrean seaport. Some see a looming conflict

KAMPALA, Uganda — To his supporters, Ethiopia’s prime minister is a renaissance man trying to reimagine the old greatness of his country....

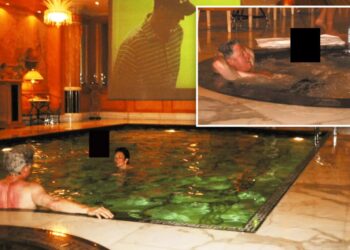

Clinton hot tub pic is from Asia trip ex-Prez took with Epstein and Maxwell — here’s more snaps from the racy night

The infamous picture of Bill Clinton in a hot tub with a mystery woman is from a 2002 trip to...