Work Advice: Karla’s final performance review, part 2

For those who missed the news, I’m stepping down as The Post’s Work Advice columnist after 14 years. For my...

‘The Emperor’s New Groove’ at 25: Kronk’s Enduring Appeal

“He’s a meme factory!” David Reynolds, the screenwriter behind “The Emperor’s New Groove,” said about Kronk, the good-hearted himbo henchman...

Why homes are ‘filtering’ up the market from the poor to wealthier buyers

A debate over the true financial condition of American families is driving pundits and economists to their elective corners. An...

The biggest mosquito-borne disease in the world has a cure. There’s just one problem

There’s a reason dengue infections are also called “breakbone fever.” Along with a mild fever, symptoms of the mosquito-borne illness...

11 New Holiday Albums That Will Make You Gasp, Laugh and Sway

Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You,” the last song to become a holiday standard, arrived in 1994...

Rob Reiner’s shocking death stuns onlookers — and spurs tributes

Legendary film director Rob Reiner and his wife Michele Singer were found dead in their California home Sunday in what...

The Panicked Moments When a Beach Celebration Became a ‘War Zone’

It was the kind of Sunday evening cherished by the Sydneysiders who call Bondi Beach home: groups of friends lolling...

Fed chair favorite Kevin Hassett on potential independence from Trump: ‘His opinion matters if it’s good, if it’s based on data’

A leading candidate to be President Donald Trump’s choice for Federal Reserve chair said that he would present the president’s...

Who Looks Like They Belong in America?

On July 7, 2025, armored vehicles rolled into MacArthur Park, in Los Angeles, where children were at summer camp. National...

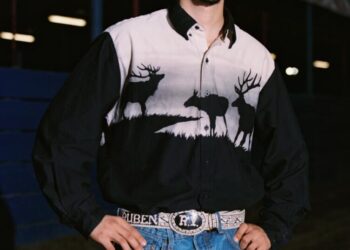

‘This feels like home.’ A fashionably late night out to the Pico Rivera Sports Arena

The belt used to belong to his father. Black leather, silver stitching, “RUBEN” spelled across the side with the initials...