After Producers Guild Awards, Can ‘One Battle After Another’ Be Beaten?

The Producers Guild of America awarded its top prize to “One Battle After Another” on Saturday night, extending an awards-season...

Gen Z Is Taking Over America’s Retirement Home

MovingPlace, from what I can tell, is to finding a moving company to haul your junk from one home to...

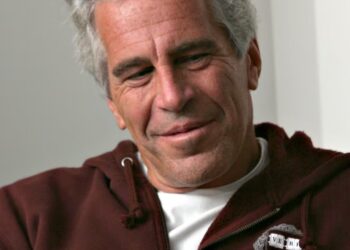

Epstein’s Creepy Medical Cabal Unmasked in DOJ Files Bombshell

A newly surfaced image from the millions of recently released Epstein files horrifyingly depicts a surgery being performed in the...

Photos show damage to major cities and tourist hotspots across the Middle East, from Dubai to Tehran

A yacht sails past a plume of smoke rising from the port of Jebel Ali, in southern Dubai. Fadel SENNA...

Iran Got Trump All Wrong

For decades, Iran managed to bluff American presidents. It deterred attacks from a superpower and carried out proxy campaigns against...

Gemini, March 2026: Your Monthly Horoscope

March runs on Mercury. Conversations, contracts, texts, emails, ideas, misunderstandings, revisions, and that running commentary in your own head all...

Cardinal found with phone during secret conclave to elect Pope Leo, book says

The secret conclave that elected Pope Leo head of the Catholic Church last May was interrupted when one of the 133 cardinals involved was...

Wary of wider conflict, European allies stress they didn’t join Iran strikes

BRUSSELS — America’s key European allies stressed on Saturday that their forces did not participate in the U.S.-Israeli attack on...

Taurus, March 2026: Your Monthly Horoscope

March reads like your ruling planet, Venus, tried on a few personalities, learned what actually feels good, and came home...

Trump says diplomatic agreement with Iran will be ‘easy ‘ now after Supreme Leader Khamenei’s death

President Trump said that he believes he can easily reach a diplomatic solution with Iran after killing Supreme Leader Ali...