Florida could yield a major payoff for Republicans as President Trump pushes states to redraw congressional districts in time for the 2026 midterms. A new map could include as many as five new red, or reddish, districts, helping Republicans keep control of the House.

Yet some of the state’s Republican leaders appear in no rush to get started, as they weigh political and unique legal questions amid internal power struggles.

A House redistricting committee met for the first time in Tallahassee, Fla., on Thursday, with members saying they were ready to get to work. But a month before the annual lawmaking session begins, neither Gov. Ron DeSantis nor legislators have proposed any maps. The State Senate has not even started studying the issue.

State Representative Mike Redondo, a Miami Republican and the House committee chairman, said that if the chamber does propose a new map, it will be by the end of the regular session in March. Any later would be “irresponsible,” he said.

But Mr. DeSantis said this week that redistricting will not take place until the spring, when he plans to call the Legislature into a special session. One of the reasons he cited for waiting was that the U.S. Supreme Court could strike down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act between now and then. Such a ruling could allow states, especially in the South, to redraw districts that were created to give minority voters a fair chance for representation.

“That obviously will be very instructive on how we do it,” Mr. DeSantis said on Wednesday.

While in some states the party is angling for a single new seat, operatives from both parties see Florida, with 28 seats overall, as a place where multiple new districts can be drawn to favor Republicans.

The Republican Party currently holds 20 of the state’s seats. At least two districts seem possible to be redrawn to favor Republicans in the densely populated areas outside Fort Lauderdale and Orlando. Mr. DeSantis is expected to pursue a more aggressive approach that could result in five new Republican districts.

But a confluence of state and federal laws present unique legal challenges that will be difficult for Republicans to untangle, especially if they take an aggressive approach.

Any redistricting effort will have to contend with an amendment to the Florida Constitution that state voters approved in 2010 that effectively banned political gerrymandering.

In other states that have undertaken redistricting, both parties have outwardly claimed political motivation for drawing new maps.

In Florida, Republicans will have to defend redrawing maps from just three years ago while skirting any explicit partisan aims, and also not running afoul of protections for minority communities. Some legislators privately worry that going too far could water down Republican advantages in some areas and result in losses in what is expected to be a difficult midterm for the party.

Republicans hold supermajorities in both Florida legislative chambers, which means that Democrats who consider the redistricting effort unconstitutional will have little to no sway over the process. Two Democratic lawmakers introduced a bill on Wednesday that would put independent citizen panels in charge of redistricting.

Republican legislative leaders seem keenly aware of the risks of any appearance of partisanship. “Senators should be aware that in prior cycles, significant litigation has followed passage of new maps,” Ben Albritton, the Senate president, wrote in a memo to his members on Wednesday.

The legal hurdles have Democrats feeling confident that a court challenge in Florida would have at least a chance of success.

“It’s so blatantly clear that this is either an extraordinary political gerrymander or going to result in an extraordinary racial gerrymander,” said John Bisognano, the president of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee.

Despite the potential legal complications, Republicans see Florida as a tipping point in the national redistricting arms race. When Texas kicked off the push for new congressional maps in August, it appeared that the party would be able to draw five seats there and pick up others in North Carolina, Indiana, Kansas, Ohio, Missouri, Nebraska and Florida.

But resistance from Republican legislators in Indiana and Nebraska stalled efforts in those states, and the new maps in Ohio were less aggressive than many Republicans had hoped. Democrats, who at first were counting only on California to redistrict in their favor, found additional opportunities: Virginia Democrats have signaled a desire to draw new maps that could add as many as three new districts for their party. And in Utah, a judge overturned its congressional map from 2021 and put in place another map that created a new Democratic-leaning district.

The slow approach in Florida underscores the rifts that have come to dominate Republican politics in Tallahassee. Mr. Albritton, the Senate president, has said that he agrees with Mr. DeSantis’s plan to redraw the map in a spring special session. That puts him at odds with Daniel Perez, the House speaker, who has emerged as Mr. DeSantis’s chief adversary.

Mr. Perez has opposed governing by special session. Florida holds regular sessions from January to March in election years precisely to give lawmakers time to redistrict, if necessary, and then have federal candidates qualify by late April. Florida holds its primary elections relatively late, in August.

Beyond waiting for the Supreme Court decision on the Voting Rights Act, Mr. DeSantis may see other benefits to delaying. Adopting a new map in the spring would give a likely legal challenge less time to wind through the courts, potentially leaving a contested map in place for the 2026 midterms. Politically, congressional candidates would have less time to campaign in their newly redrawn districts — a sprint likely to benefit Republicans, who are better funded and better organized in the state.

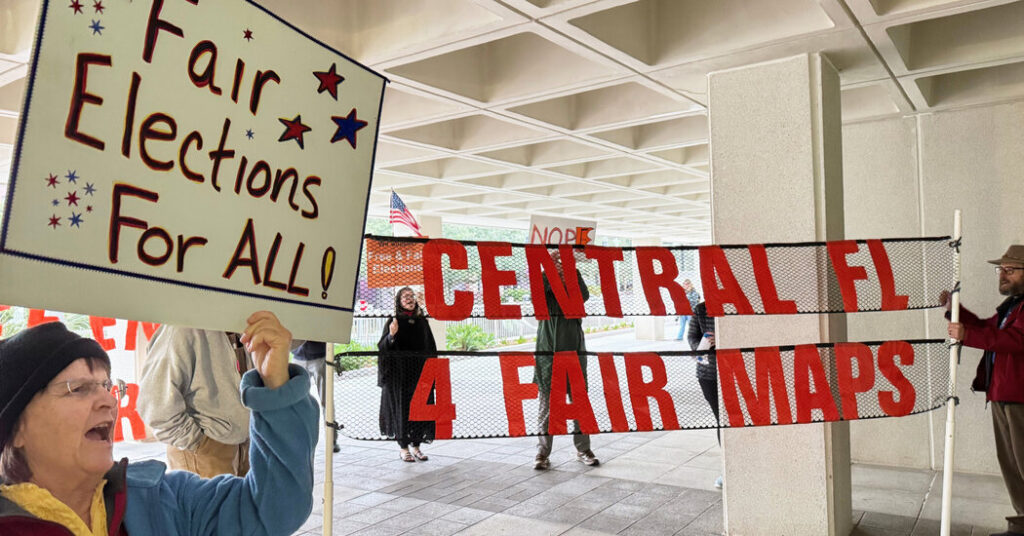

Thursday’s committee meeting drew dozens of opponents, some of whom traveled from around the state to attend, though lawmakers took no public comment. Before the meeting, which lasted 25 minutes, roughly 100 demonstrators gathered outside the old Florida Capitol, holding signs and chanting, “Fair districts for all!”

Ruth Rauch, a 70-year-old small business owner from Sarasota, said “outrage” drove her to show up.

“This is against our Constitution, and it’s blatant partisan gerrymandering,” she said. “It’s just disenfranchising voters.”

Patricia Mazzei is the lead reporter for The Times in Miami, covering Florida and Puerto Rico.

The post Redistricting Gets Off to a Slow Start in Florida appeared first on New York Times.