If you want to understand a culture, the historian Johan Huizinga wrote, find its amusements.

In 1998 the Tennessee Foxtrot Carousel went up in downtown Nashville, a music town then enjoying a spurt of development that would bring its first professional football stadium, an exuberant new building for the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, and other modernities.

Foxtrot, by contrast, was an aggressively esoteric throwback.

The carousel’s 36 fiberglass “horses” were drawn from well-known Tennessee history — the frontiersman Davy Crockett getting mauled by a bear, the singer Kitty Wells wailing from her tour bus — but also forgotten figures like Charlie Soong, Vanderbilt University’s first Asian graduate, receiving his diploma astride a Chinese dragon of bright oranges and greens.

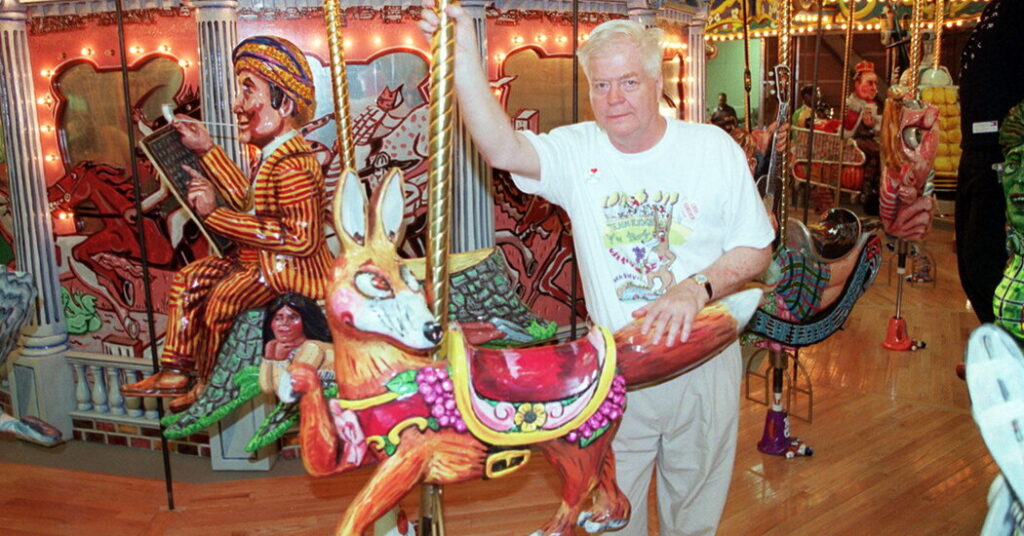

The New York artist Red Grooms, a Nashvillian by birth and Hillsboro High School alumnus of 1955, took three years to design the ride and oversee its construction with a carousel workshop.

A founder of New York’s happenings scenes in the late 1950s, he and his first wife and former creative partner, Mimi Gross, were among the generation that fought to liberate Pop Art from the critical gaze. When the carousel opened to the public, journalists found in this “people’s merry-go-round” an assertion of local memory and handicraft amid urbanization, and a splash of humanity in a downtown full of bars. A calliope soundtrack drew children, and a brochure schooled parents on its wraparound panels.

Then, in 2003, it disappeared. “We were barely even warned it would close,” Grooms recalled in an interview. “Spinning one day, then silent the next.”

For reasons that vary by teller — debt, falling tourism, a faulty thermal plant downriver — Grooms’s ride was dismantled. The Tennessee State Museum acquired its pieces, and they have been in storage since. Across the river, four years later, and highly visible from where the carousel sat, the city installed a sleek abstract sculpture by Alice Aycock.

Today, amid a new real estate bubble — a rash of skyscrapers and condominiums, and a $2 billion dollar stadium replacing the old one — Nashville misses Grooms’s vestige of old, weird America.

The Tennessee State Museum, short on the requisite cash, this month issued a Request for Information (R.F.I.) through the state’s central procurement office to query potential donors for a revival of the carousel.

This coincides with an exhibition at the David Lusk Gallery in Nashville, where dozens of Grooms’s first sketches and models for the ride, up through Dec. 20, acquaint a new generation with a lost legend of public art, in a town famous for its churn.

Ghosts and Machines

Last month, Lusk and I circled four ghostly, scuffed-white Styrofoam sculptures, cut between 1996 and 1998 by Grooms’s assistant Tom Burckhardt. The carousel foundry cast the fiberglass figures from these models, then Grooms painted the fiberglass.

Soong is here. So is the Confederate widow Adelicia Acklen and Eugene Lewis, who in the 1890s commissioned Nashville’s Parthenon. None are household names, yet it is hard to cross to the Vanderbilt side of town without Acklen Avenue or the park that holds Lewis’s scale replica of the Parthenon.

“I think of Red throughout his career as a cultural historian,” Lusk said, leaning in to examine the miniature Parthenon the foam Lewis holds aloft.

A Memphis dealer, Lusk never personally saw the ride. In the decade since he expanded to Nashville, the metropolitan area has grown by a third of a million people. “There is still so much lore about this carousel that people seem to remember it so fondly,” Lusk said. “If they remember it at all.”

To art lovers I spoke with, the carousel seems to live on as the scapegoat of a town eager to raze its own visual heritage.

Though she only distantly remembers the carousel from childhood, the artist Lillian Olney, Hillsboro 2011, said, “I’m sad that Red Grooms and William Edmondson” — the Nashvillian who became the subject of the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal solo exhibition by an American sculptor — “get more love and attention in New York than in Nashville.”

“I hate that I think about that stupid Nathan Bedford Forrest statue off the interstate more than I think about the carousel,” Olney said of another fiberglass landmark of 1998, depicting the Ku Klux Klan founder, which outlived the carousel by 18 years.

The artist Curtis Godino, part of a team who recently helped Grooms paint an imaginative mural of the carousel at Lusk, had always revered Grooms as an interdisciplinary legend of Manhattan. “It blew my mind to learn he’s from Nashville,” said Godino, who moved to Nashville from New York in 2023. “It’s insane to me that that carousel isn’t on display.”

Over clementines on a front porch, Chris Crofton, the comedian and columnist who moved to Nashville during Foxtrot’s heyday and recently ran for City Council to combat the cost of living here, doubted whether an audience for such a regional oddity exists anymore.

“In a boom town there’s very little interest in history,” Crofton observed bitterly. “Do you think the guys in the gold rush wanted to hear about the history of Alaska? No. They want to find out if there’s gold there and then get the hell out if there wasn’t. You want a carousel? Go somewhere where people are hopeful.”

The Push for Revival

By contrast, legacy Nashvillians see today’s development boom as the perfect reason to resurrect Grooms’s ode to the state.

Over iced tea at her home in Franklin, Tenn., Trudy Byrd was diplomatic: “I think it’s a revenue source.”

In the early 1990s Byrd co-founded the nonprofit that commissioned the carousel. Grooms, a family friend of Byrd’s, was fresh off his rollicking “Red Grooms at Grand Central” exhibition at Grand Central Station in New York, where Mayor Ed Koch and sundry thousands roamed Grooms’s comic-booky sculptural replicas of the city, and “rode” the artist’s subway car.

So it wasn’t hard, back then, Byrd told me, to raise nearly $2 million from private donors to fund the ride on a plot of city land. The nonprofit leased it for a dollar a year, for 99 years.

“With some fund-raising, it could easily be brought back to life. We’re a different town now,” she said, but “it gives me chills to think of it not being a ride.”

Ashley Howell, the director of the Tennessee State Museum, over coffee across the street from the museum’s new $160 million building, sounded eager but helpless.

“People love it. I love it,” Howell said. “It couldn’t just happen with the normal budget.”

In 2019 the museum’s carousel committee weighed options for its revival. A stationary sculpture would disappoint, they decided. It could, instead, be a mechanized one. (For which the remounting of the “art carnival” Luna Luna is one precedent.) Or, best of all, a functioning ride. If a ride, on what land? With what insurance? The motor alone would cost an estimated $500,000 to fix, the committee found.

The conservator Mark Bynon, who assessed the carousel’s 130 individual painted pieces in 2019, recalled that “because they had been ridden and kicked for years, and because of their storage in all these hot summers, the fiberglass has swelled and cracked, allowing the paint to delaminate,” he said by phone from his workshop in North Carolina. (Grooms used oil and synthetic paints.)

“It’s got to be treated like everything else in the museum,” as one of its 140,000 precious objects, Bynon said. Even restoration, with fiberglass repairs and touch-ups to paint, he cautioned, “would change the status of the artifact.” Bynon recommended replicating Grooms’s figures.

Grooms’s carousel illustrates the financial challenge of regional museums, which scrounge to raise funds and then have to decide whether to add a wing or spend the money on upkeep for their collections.

“The piece is iconic,” Bynon said. “Working with those characters so closely, some of them even end up in your dreams.”

A Totem Pole for a Bygone South

On a stuffy spring day, a caretaker led me through the museum’s off-site warehouse, flicked on the lights, and there they stood: like the Terracotta Army, Grooms’s time-lapse of musicians and socialites and businessmen, their faces locked in expressions of industry or glee unknown for a generation. Their lacquered surfaces shone like candy.

Some wear was visible. A crack has split the torso of the 19th-century rabbi Isidore Lewinthal. But what most draws your eye is the detail of this cartoon scholarship.

Grooms has rendered country music’s most sacred stage, the Ryman Auditorium, home of the Grand Ole Opry from 1943 to 1974, through its prehistory: Captain John Ryman, the benefactor of the church in 1885, steers his riverboat. Samuel Jones, the reverend who packed its seats, preaches from a “horse” of burning hellfire. Beside them, Lula Naff, the manager who welcomed country music’s founding radio show to the building, unrolls a handbill.

In their mausoleum, they seemed like witnesses for a city in flux. Twice, in the 1970s and 1990s, Nashville almost razed the Ryman. Writers and singers intervened each time, and this month it is hosting tours for the Opry’s 100th anniversary. As a work of visual history, the carousel grounds such mood swings.

As an artwork, it asks questions of psychology. When a child learns history, for instance, does he picture it with the factual mind or the imaginative one?

That child is now 88. Grooms brought me to his Manhattan apartment, sat me down with a coffee before his enormous cartoon painting of Jackson Pollock, and explained that the Tennesseans he grew up around had been born in the 19th century.

Grooms’s mother had seen the great Anna Pavlova dance at the Ryman, he told me. That’s why his Naff wears a tutu and pointe shoes. As a teenager he worked at a frame shop, the Lyzon Gallery, where two huge sculptures by Edmondson, the son of former enslaved people and “one of the greatest artists of the 20th century,” Grooms marveled to me, propped up the gallery’s sign out front. On the carousel, Edmondson chisels a bird you are meant to ride.

Regarding revival, Grooms, an earthy and kind gentleman, was blunt. “Just put the thing back together,” he said, shaking his pouf of white hair. “Don’t be precious about a carousel. They either think it’s not worth a nickel or it’s worth a zillion dollars.”

“With the carousel, everybody thought I was trying to bring my hometown up to snuff,” Grooms said, his signature roadside honesty in full flex. “But forget about it, I was just after the ticket prices.” He glanced at his wife, the artist Lysiane Luong Grooms, then back at me. “I didn’t really mean that,” he said through a smirk. (In 1998, a ride cost $1.50.)

The point was that Grooms intends his sculptures to be used, not assessed. Right now several of his large-scale environments are installed (and enterable) in Queens, Brooklyn and Yonkers, N.Y. None in Nashville.

On the heels of the museum’s new call for help, “Red Grooms: The Tennessee Foxtrot Carousel,” will test the ground. Not just for Grooms’s late-career representation. (Marlborough, his gallery of 50 years in New York, closed last summer.) And not just for his extravagant brand of play-art. Like the animating mechanism of his lost ride, the show wheels back into view a piece of the old Nashville.

It will test the appetite, and the motion sickness, of the new one.

The post Nashville Closed a Red Grooms Masterpiece. Now the City Wants It Back. appeared first on New York Times.