The proliferation of documentaries on streaming services makes it difficult to choose what to watch. Each month, we select three nonfiction films — classics, overlooked recent docs and more — that will reward your time.

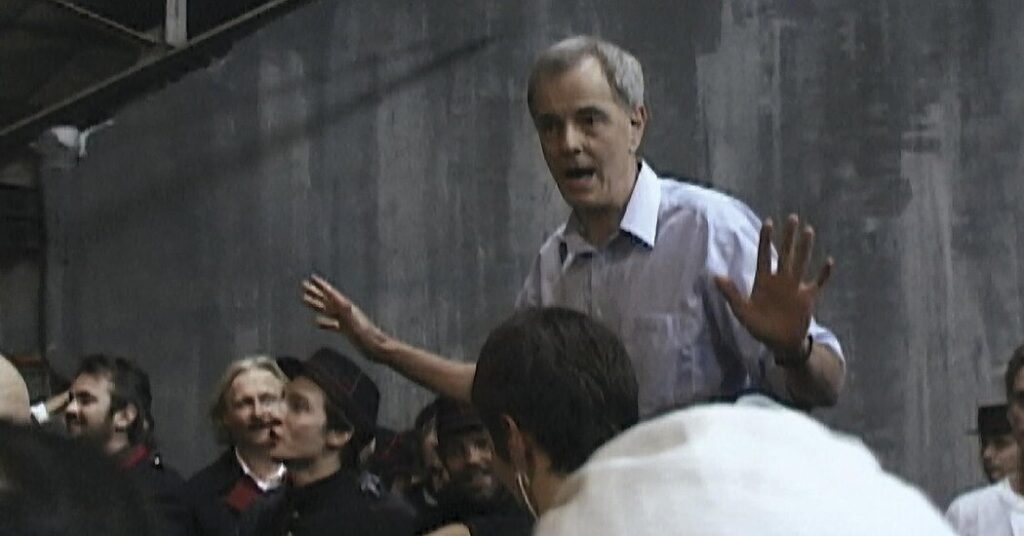

‘The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins’ (2001)

Stream it through the National Film Board of Canada. Rent it on Amazon.

One of the oddities of Oscar history is that “The War Game,” which won the award for best documentary feature in 1967, is not, in the strictest sense, a documentary. Rather, it mimicked the form of one to imagine the aftermath of a nuclear attack on Britain. Peter Watkins, the director, who died last month, spent much of his career blurring the lines between fiction and nonfiction. Regrettably few of his films are available to stream, but Geoff Bowie’s “The Universal Clock,” a Canadian documentary on the making of his staggering “La Commune (Paris, 1871),” provides a strong introduction not just to Watkins’s working methods but also to his philosophy.

The title refers to the restrictions then typically imposed by commercial television: the idea that a program had to run 47.5 minutes for an hourlong slot and 23.5 minutes for a half-hour slot. “La Commune,” backed by European broadcasting, came to 5 hours and 45 minutes in its long version. But the length is only the start of the project’s ambition. Watkins had invited actors — generally nonprofessionals — to restage a brief historical moment in 1871 when members of the French working class took control of Paris and governed it with leftist ideals before they were violently suppressed two months later. Watkins’s film shows the events unfold in the present tense, as documented, anachronistically, by TV reporters.

Bowie interviews the actors who took part in the experiment, whom Watkins instructed to be themselves, and to express their own positions on what was happening, instead of speculating on how they might have reacted in the 19th century. (“I don’t want you to wear a mask,” he tells one performer.) “La Commune” was shot in sequence, and frequently in long takes. The cast members appear to become partisans of Watkins’s working methods (“This film shows me that what I see on TV is really mediocre, frankly,” one woman says) and bring their own histories to the film. Watkins also shares his theories on the “monoform,” the name he gave to what he saw as the audiovisual barrage offered by ordinary television, which he felt was conceived with a predetermined meaning and sought to manipulate viewers when it should be trusting them. Bowie supplements footage of Watkins’s radical shoot with interviews of TV power players gathered for a conference in Cannes, France. They are about as cautious in their views as Watkins is vanguard.

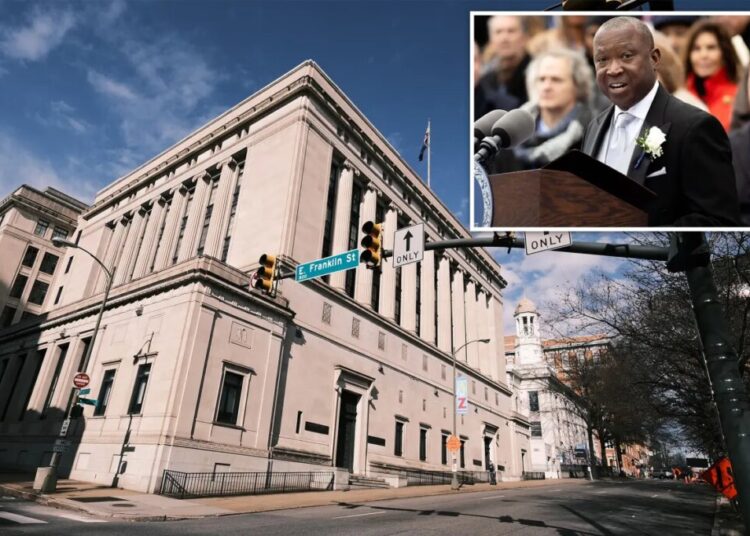

‘Best of Enemies’ (2015)

Stream it on Fandango at Home, Pluto, Roku, Tubi and YouTube Movies & TV. Rent it on Amazon and Apple TV.

Watkins would probably not have approved of the televised clash memorialized in “Best of Enemies” — although there wasn’t exactly a foreordained outcome when ABC paired the left-wing Gore Vidal with the right-wing William F. Buckley for a series of debates aired during the 1968 Republican and Democratic national conventions. Watching clips of the men’s bouts today is almost like watching transmissions from another planet. With a banter that seems directed at a viewership that no longer exists, if it ever did, the two patrician writers compete to see who can land the most devastating witticism. Even when Buckley lost his cool, calling Vidal a homophobic slur and threatening to hit him (“Stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in the goddamn face and you’ll stay plastered”), he phrased it in a perplexing way. Plastered?

The directors Robert Gordon and Morgan Neville (this was well before Neville’s Anthony Bourdain film raised questions over its use of A.I.) bring on experts like the filmmaker Matt Tyrnauer, a friend of Vidal’s who had also edited his writing, and the Buckley biographer Sam Tanenhaus, a former editor of The New York Times Book Review, to appraise the men’s legacies. Buckley’s brother Reid Buckley expresses continued disdain for Vidal, whom he says always leaves him with “a residue, in my opinion, when I watch him, of nausea,” while the linguist John McWhorter, currently a New York Times Opinion writer, makes observations about the way Vidal and Buckley talked.

All of which is interesting enough, but it pales compared to watching two political commentators — always bridesmaids themselves in politics — who plainly despise each other try to keep smiling on live TV. The film suggests that both men remained obsessed with their encounters: Buckley wrote an essay trying to understand why he snapped, while Vidal, Tyrnauer says, screened the debates at home. “Best of Enemies” means to document a moment in the history of television, but it’s also a study in the psychology of the 20th-century public intellectual.

‘My Mom Jayne’ (2025)

Stream it on HBO Max. Rent it on Amazon, Apple TV, Fandango at Home and YouTube Movies & TV.

The “Law & Order: SVU” star Mariska Hargitay was just 3 when her mother, Jayne Mansfield, died in a car crash in 1967. Hargitay herself was in the back seat and only survived because her 6-year-old brother had the presence of mind to ask where she was — that is, why she hadn’t been retrieved from the wreck. In “My Mom Jayne,” Hargitay sets out to learn more about a parent of whom she had no memories, and whose public image differed starkly from her private life.

Early on, we see a clip in which Mansfield was a guest on Groucho Marx’s show; Marx emphasizes that she is far more than the ditzy-blonde avatar her audiences perceived. In another clip, she bristles that her figure had received more attention than her intellect. “My Mom Jayne” explains she was multilingual and had a passion for piano and violin. She was exacting about her career and harbored ambitions to be a serious actress, but was told at an early Paramount audition that she was wasting her “obvious talents.” Hargitay confesses to being upset by the high-pitched, Marilyn Monroe-esque voice with which Mansfield spoke in movies and on TV, which wasn’t how she talked in life. (There is brief footage in which she speaks about wounded veterans that the movie presents as showing the real her.)

But “My Mom Jayne” is more than a simple effort to show that Jayne Mansfield was deeper than her fans knew at the time. Her troubled relationships with men and early death left Hargitay with tangled family dynamics (she was raised by Mickey Hargitay, the bodybuilder who was Mansfield’s second husband, and Mickey’s later wife, Ellen, in what’s portrayed as a loving, close-knit group) and a lot of questions about the past. “My Mom Jayne” is in some ways closer to documentary psychodramas like Lynne Sachs’s “Film About a Father Who” than it is to a standard celebrity portrait, and it has a tenderness that is rare in the genre.

The post Three Great Documentaries to Stream appeared first on New York Times.