The philosopher C. Thi Nguyen remembers when misery turned out to be his salvation. He had just graduated from college and was living in a Boston suburb, working as a tech writer. “I made a lot of money,” he recalled on a recent afternoon in his Salt Lake City home. But the cash came at the cost of spending too much time doing something he hated. “That was the death of the soul.”

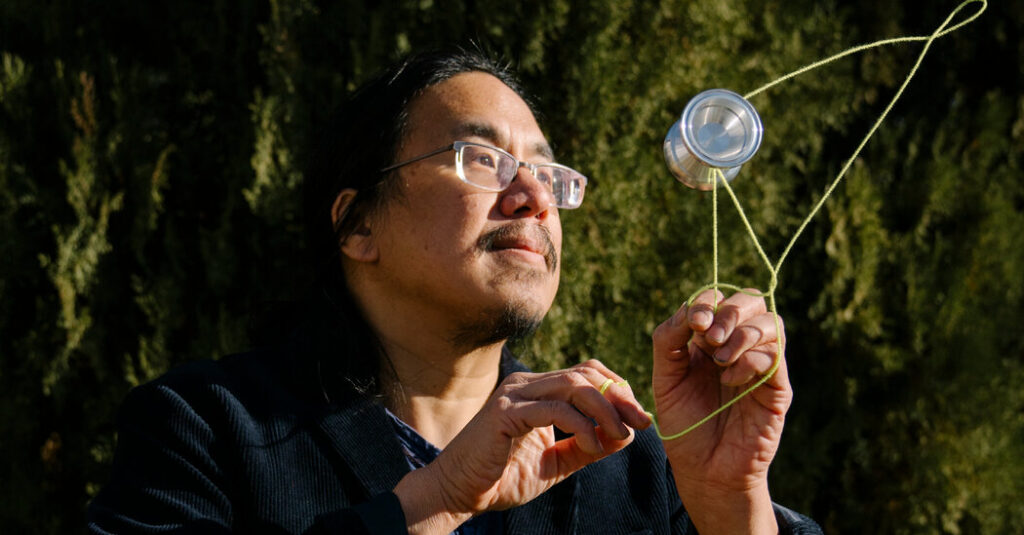

So Nguyen enrolled in the graduate program in philosophy at U.C.L.A., picking up the subject he had majored in at Harvard. Completing his Ph.D. took him 11 years, though in his defense, he was also working as a food writer for The Los Angeles Times. His double life as a philosophy grad student and professional food journalist was just one unconventional twist in a trajectory that’s been full of them. In addition to cultivating a life of both the mind and the senses, he also loves games: board games, video games, role-playing games, games of skill and games of chance — not to mention fly-fishing, rock climbing and, lately, yo-yoing.

You might not think of these last three activities as games, but like the others, they present a participant with a goal to be pursued under certain constraints. For Nguyen, the point — and pleasure — of games is play, not efficiency; a person who simply wants to catch more fish would trade Nguyen’s feathery hand-tied flies for a big net or a blast of dynamite.

For a long time, Nguyen was told to keep his personal passions separate from his scholarship. “No one in the world, in philosophy or out, was interested in the philosophy of games,” he said. “Like I was forbidden from working on it in grad school.” (He wrote his dissertation on the epistemology of moral testimony.) But now, in another unlikely turn in Nguyen’s unorthodox career, his private pastimes and his principal vocation have converged.

This week, Penguin Press is publishing “The Score,” his mind-expanding exploration of the philosophy of games, showing how scoring systems teach us what to desire and make our motivations legible to one another. The book arrives at a time when everyday life has been gamified. Tech platforms keep us “engaged” with applause and leader boards and sprays of digital confetti. Apps ply us with rewards and metrics for optimizing our diet, our exercise, our sleep. As a games enthusiast, Nguyen noticed a discrepancy that seemed to be getting ever more extreme: In some domains, trying to increase your score can be fun and satisfying, while in others — like getting rich as a tech writer — it can utterly crush your spirit.

Nguyen, whose day job is as a philosophy professor at the University of Utah, contrasts the delightful thrill of playing games like basketball, The Legend of Zelda and Dungeons & Dragons with the demoralizing pursuit of university rankings, page views and social media likes: “Why is it that mechanical scoring systems are, in games, the site of so much joy and fluidity and play? And why, in the realm of public measures and institutional metrics, do they drain the life out of everything?” His hope, as he puts it in the subtitle, is to teach readers “How to Stop Playing Somebody Else’s Game.”

“The Score” is so exuberant and readable that the depth and seriousness of its insights almost sneak up on you. Nguyen shows how scoring systems tantalize us by making certain measures of success seem undeniable. Billionaires will chase more money — to the point of friendlessness and exhaustion — because their entire self-worth has been captured by the idea of “number go up.” Conspiracy theories like QAnon are gratifying because they resemble a game: Connecting the dots among conspiring elites is just challenging enough to yield a sweet sense of control.

Nguyen, 48, is someone who likes to “maximize processes.” He roasts his own coffee beans with a toaster oven-like contraption that he keeps on his porch, and he uses a manual-lever espresso machine that forgoes the usual blast of steam for the slow pull of hand pressure. When I visited in December, the house where he lives with his spouse, Melissa Hughs, a chemist, and their two young sons was crowded with miscellaneous objects — yo-yos, antique masks, artwork by each member of the family, Post-its doodled on by friends, a trampoline, a hammock, a bass guitar — none of which could be Marie Kondo’d because every item brings him evident joy.

Nguyen savors how games provide a container, or a “temporary shape,” for “some delicious form of action.” He wants us to understand games as a form of art. (His previous book, “Games: Agency as Art,” was published in 2020.) The rules act like a trellis, restricting what methods we can use to achieve our goal while also opening up new possibilities: “They create the background conditions that make it likely that your own actions will be elegant, fascinating and thrilling.” Visual art allows us to try on different ways of seeing; games allow us to try on different ways of doing.

The constraints of rock climbing and fly-fishing taught Nguyen how to refine his movements in ways that don’t come naturally to someone whose instinct is to move big and fast. “I tend to be really quick and sloppy,” he said. “I really like these things that kick me if I don’t slow down enough to pay enough attention.” He described how challenging but also rewarding it is to be able to go out on an expanse of water, soften his focus and “notice that there’s this tiny dimple of a trout feeding.”

The unusual shape of his philosophy career is also the result of learning how to slow down enough to focus on what years of academic training had encouraged him to ignore. The American way of philosophy — analytic, logical, rigorous — trained him to think clearly and carefully. But after getting his Ph.D., the philosophical establishment was telling him that “most of the things I was interested in were not interesting.” He was teaching as an adjunct and doing philosophy of aesthetics. “It was this weird corner of philosophy where people are willing to pay attention to the weirdness of a phenomenon.”

His fellow philosophers credit such frustration with helping to fuel his creativity. “I think Thi’s fearlessness was born partly out of his feeling marginalized and readiness to leave the discipline,” Elisabeth Camp of Rutgers told me. “He’s not beholden to the big authority figures in the way that many people are.” He’s also not beholden to the old rules of specialization. This may be the only book in existence that discusses the game of Twister, the ethics of Aristotle and the mechanics of bureaucracies. For Sanford Goldberg of Northwestern, the willingness to pursue such unexpected points of connection reflects Nguyen’s healthy irreverence for tradition: “That’s the kind of not recognizing borders or boundaries that I think is just beautiful.”

My day with Nguyen began right after lunchtime and finished nearly 12 hours later, just after midnight. As the afternoon light began to fade we drove to a nearby canyon where he likes to climb. Using no equipment other than climbing shoes and a mat on the ground for safety, he scrambled up a face of seemingly smooth granite that contained handholds and footholds that I couldn’t see and could barely feel as I ran my hand along the surface.

I didn’t even entertain the possibility of climbing. But yo-yo was something I thought I could do. I had vague memories of playing as a kid. Surely I could get a yo-yo to go up and down. I mean, how hard could it be?

Back at his home, Nguyen brought out various toys for me, Hughs and a visiting friend of theirs to try: yo-yos, spin tops, a Japanese ball-and-cup thingumajig known as a kendama. My reflex was to thrust my hand out to grab the yo-yo, when I should have been flicking my finger with a tiny tug and letting the string pull the yo-yo back to me. When I finally caught it I felt a small trill of elation. Then I proceeded to awkwardly lunge for the yo-yo on the next try and didn’t catch it again.

“All of my hobbies involve basically micro-dosing epiphanies,” Nguyen said at one point. “Every time you’re yo-yoing, you’re like, If I change my angle this much, or if I pull a little bit here, or if I drop it, oh, then it works!”

The fact that the stakes are so low is not a deficit of the yo-yo (or the kendama, or D&D, or fly-fishing); low stakes are part of the point, allowing us to move from one game to another. Nguyen argues that problems emerge when the stakes become all-consuming, taking over our sense of self and dictating what we should value. Metrics feel stultifying because they provide a seductive clarity that is nevertheless a thin measure of the rich and complex world they purport to represent.

The philosophy of games turns out to be a nicely shaped container for exploring thorny questions about trust, knowledge and authority. Nguyen wrote two endings for “The Score” and included both. Ending A is “The Cynical Sad One”; Ending B is “The One With a Little Measure of Hope.” In Ending A, we are trapped by the metrics; in Ending B, games help us understand how play is connected to freedom. He tries to offer the same inconclusiveness to his philosophy students. “If you come out of this with exactly my views, I have failed,” he said. “That is not what I want to do with a classroom or a reader.”

But getting people to recognize what game they’re playing can be a challenge when phony knowingness is more lavishly rewarded than genuine doubt. “I literally have students screaming, ‘Tell me the [expletive] answer, Thi!’” he said. “I’m like, if you come out of this more confused about what’s going on in the world and how to figure it out, then I have won. This is my goal.”

Jennifer Szalai is the nonfiction book critic for The Times.

The post Why Keeping Score Isn’t Fun Anymore appeared first on New York Times.