Photographs by Christopher Payne

On Mars, in the belly of a rover named Perseverance, a titanium tube holds a stone more precious than any diamond or ruby on Earth. The robot spotted it in 2024 along the banks of a Martian riverbed and zapped it with an ultraviolet laser. It contained ancient layers of mud, compressed into shale in the 3.5 billion years since the river last coursed across the red planet. Inside those layers, the rover found organic compounds. Its camera zoomed in and noticed leopard-like spots. Scientists had previously observed similar spotting patterns, but not on Mars. They’d seen them on Earth, in muds that once teemed with microbes.

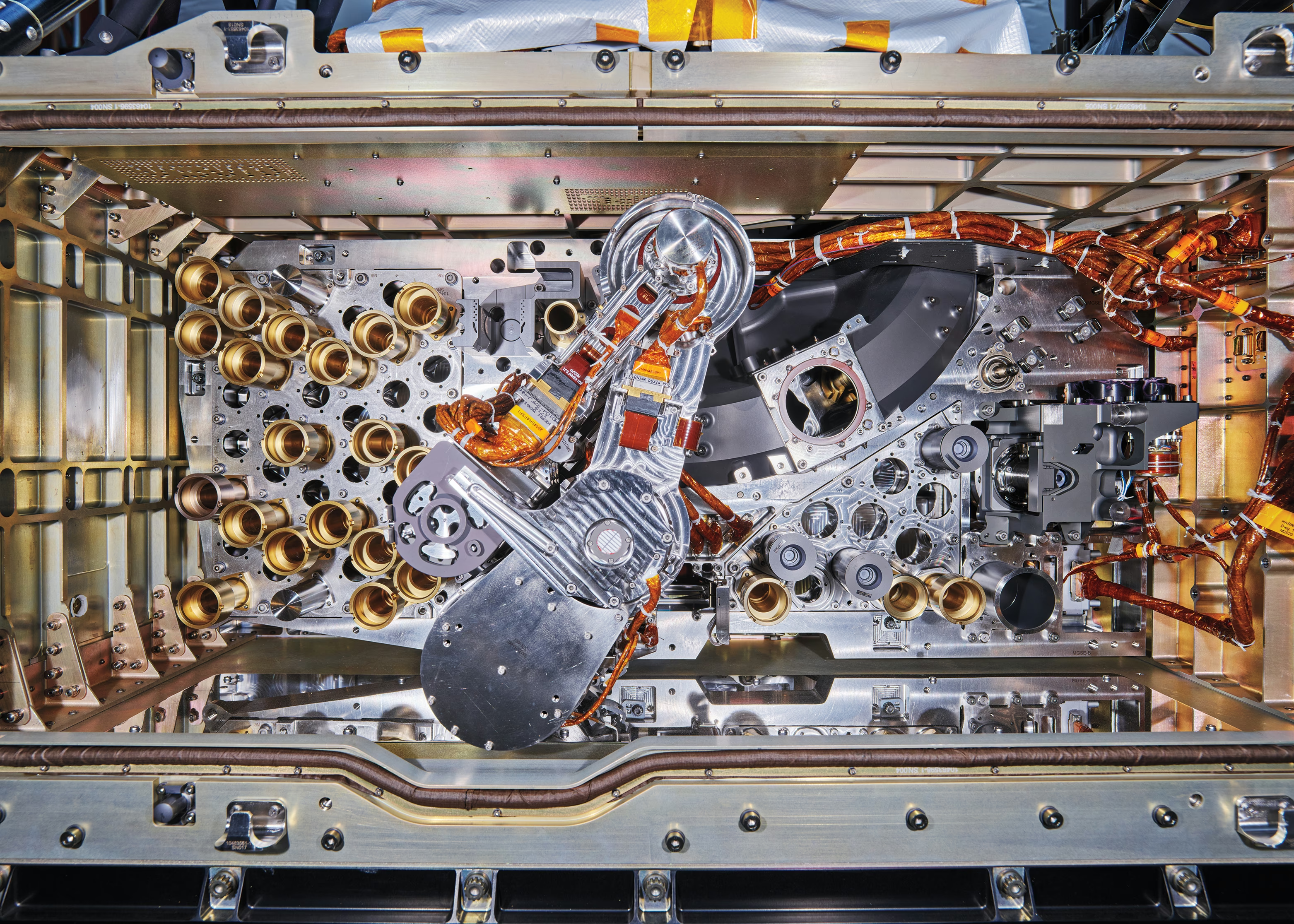

The rover tucked a core sample about the size of a piece of chalk into a treasure chest in its chassis. There the rock will remain until a future robot parachutes down onto the Martian surface, grabs the chest, and launches it back to Earth. If scientists are able to inspect it in person, and they find that Mars was indeed once alive with microbes, we would know that life on our planet is no cosmic one-off. We would have reason to believe that it has emerged on many of the hundreds of billions of planets that exist in our galaxy alone. The cosmos that we look up into at night would no longer seem a cold void. It would shimmer with a new vitality.

Perseverance is among the latest in a lineage of interplanetary robotic explorers that NASA has built across almost 60 years, for about $60 billion. That’s less than what Mark Zuckerberg spent on his struggling metaverse. At NASA, it paid for hundreds of spacecraft that have flown past all of the solar system’s planets, dropped into orbit around most of them, and decelerated from flight speed to reach the surface of a few. These missions have disclosed the scientific qualities of other worlds, as well as the look and feel of them, to all humanity, and for posterity too.

Most of these missions, including nine of the 11 that have landed on Mars, were run out of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, near Pasadena, California. The mission to retrieve the chest inside Perseverance was, until recently, the largest, most important project at JPL. About 1,000 people there were working on it. But it’s no longer moving forward, and may never happen.

Last spring, President Donald Trump bluntly expressed his vision for science at NASA in his first budget request. Along with extensive layoffs, he called for 40 of the agency’s 124 science missions, including Mars Sample Return, to be defunded, and for the surviving missions to make do with less. Among NASA scientists, the request was demoralizing; within months, its major science centers lost thousands of staffers to buyouts and cutbacks.

On a hot day in late October, I visited JPL’s Mars Yard, an outdoor sandbox where rovers practice their off-world skills. The lab had just let 550 staffers go, its fourth force reduction in two years. One of Perseverance’s test models sat back in the garage, resting in the shade, while its more nimble successor—a rover prototype with a llama-like neck—army-crawled over some boulders in the morning glare. A senior scientist at JPL had told me that he’d never seen the place so empty and lifeless, so drained of enthusiasm. But I was a guest in the Mars Yard, and my hosts were dutifully chipper, even when the little autonomous rover got stuck on a sand dune, even when they explained that it isn’t currently slated to visit any other worlds.

Only the governments of rich countries send robotic explorers to other planets. And only the United States has sent them past the asteroid belt to Jupiter and beyond. For decades, this has been a part of America’s global cultural role: to fling the most distant probes into the solar system, and to build the space telescopes that see the farthest into the cosmos. The U.S. has led an unprecedented age of cosmic discovery. Now Trump is trying to bring that age to an end, and right at the moment when answers to our most profound existential questions finally seem to be within reach.

The way David Grinspoon remembers it, the attack on NASA headquarters began with the plants. In February, a few weeks after Trump took office, Grinspoon, who was then a senior scientist at the agency, walked into a newly barren common area at headquarters in Washington, D.C. On the windowsill, the potted plants that had previously sat between models of NASA’s signature spacecraft had been removed; he was told that the order to remove them had come down from the new administration. (A spokesperson from NASA said the plants were removed after the agency terminated a plant-watering contract “to save American taxpayers money.”)

Grinspoon could live without the office greenery. Its confiscation was trivial, comic even. He’d been hired by NASA to lead strategy for the agency’s astrobiology missions. He tried to stay focused on that, but he grew more alarmed a few weeks later, when the administration disbanded NASA’s Office of the Chief Scientist, a team of six that advises agency leaders on scientific matters. DOGE officials started walking the halls. They snapped pictures of empty offices, as evidence that people weren’t working. “That was infantilizing,” Grinspoon told me. His colleagues put Post‑it notes on their doors to let their new minders know when they went to a meeting, or to get coffee.

Many NASA staffers rank among the most talented people in their fields. At JPL, I met Håvard Fjær Grip, an engineer who helped develop a small helicopter that stowed away on the Perseverance rover. After the hawk-size chopper plopped out onto the Martian surface in 2021, Grip, who was also its chief pilot, got it airborne. It was built for only five flights but managed 72, and it flew all of them with a tiny swatch of fabric from the Wright brothers’ Flyer 1 tucked under its solar panel. Grip led me to an 85-foot-tall steel cylinder, a simulator capable of generating harsh Martian conditions. Through its porthole window, I saw where he’d placed a new carbon-fiber rotor. He wanted to get it spinning at nearly the speed of sound. He hoped that it could power a larger chopper up and down the cliff faces of Mars.

Work like this requires world-class scientific infrastructure and skill. By April, Trump appeared to be trying to rid NASA of both. The White House had already offered government workers a blanket buyout. Janet Petro, whom Trump had appointed acting administrator of NASA, was openly encouraging staffers to take it. She began sending emails warning of impending layoffs.

Trump’s budget request, released in May, called for a 47 percent cut in funding for the agency’s science missions and deep reductions in staff at its major science centers, JPL and Goddard Space Flight Center. Congress hasn’t passed this request, and as of this writing it seems likely to reject Trump’s severe cuts. But during the crucial window when NASA’s staff was considering buyouts, Petro indicated that the president’s request would guide policy.

Every NASA science unit was told to draw up a new budget, Grinspoon said. It was like planning a strike on the fleet of spacecraft that the agency has spread across the solar system. If the cuts in the request were implemented, satellites that monitor the advance and retreat of Earth’s glaciers, clouds, and forests would splash down into an undersea graveyard for spacecraft in the remote Pacific Ocean. A robot that is on its way to study a gigantic Earth-menacing asteroid would be abandoned mid-flight, as would other probes that have already arrived at the sun, Mars, and Jupiter. The first spacecraft to fly by Pluto is still sending data back from the Kuiper Belt’s unexplored ice fields. It took almost 20 years to get out there, and the small team that runs it costs NASA almost nothing. It would be disbanded nonetheless, and contact with the probe would be forever lost. Future missions to Venus, Mars, and Uranus would also be scrapped.

A whole national endowment, funded by American taxpayers and built over decades, was at risk of being vaporized, with consequences that could linger for a generation or more. Among the “many levels of pain” that Grinspoon experienced, he found it hardest to cut back the programs that train young scientists to do the hyper-technical work of searching for life among the stars. “It’s like eating your seed corn,” he said.

Trump seems to see NASA primarily as a means of ferrying astronauts to and from space. He made this view explicit in July when he asked Sean Duffy, his secretary of transportation, to succeed Petro as the agency’s acting administrator. Human-spaceflight missions are useful to the president as nationalistic spectacles; he worries that the Chinese will land on the moon before Americans return there. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act increased funding for NASA’s human-spaceflight centers (which, unlike the major science centers, are all in red states). But although crewed missions can inspire awe and are worth supporting, they provide far less scientific return than robotic probes or space telescopes, which are purpose-built to disclose new laws of the cosmos.

[From the January/February 2015 issue: Charles Fishman on 5,200 days in space]

By early summer, the people who work on NASA’s science missions were decamping to private-sector jobs that pay more, but are perhaps less inspiring. Email send-offs for longtime employees dominated Grinspoon’s inbox. He didn’t blame his departing colleagues for taking the buyouts. The missions that they’d looked forward to working on were likely to be scratched. And they knew that they might not get the same severance if layoffs came. Grinspoon himself stayed until September, when his position was eliminated.

The eight-story clean room at Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt, Maryland, is a hallowed space. It was the main attraction on the tour that the center’s most recent director, Makenzie Lystrup, used to give to visiting members of Congress, foreign heads of state, and other VIPs, before she abruptly resigned in July. In this enormous bay, NASA built the Hubble Space Telescope and the other orbital observatories that have brought the deep universe into the everyman’s ken, revealing its endless fields of galaxies, its exploding stars, its black holes. No other kind of science mission can match the power of these space telescopes to unveil the universe.

The clean room’s current resident, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, is currently scheduled to launch in late 2026. At regular intervals until then, vents will pump in blasts of pure nitrogen and compressed air, purging the bay of dust that might otherwise trickle into the telescope’s exquisite cosmic eye. Scientists and engineers will file in, wearing white bunny suits and booties, to tend to America’s next great observatory up close. Like Lystrup, some of them worry that it will be the country’s last.

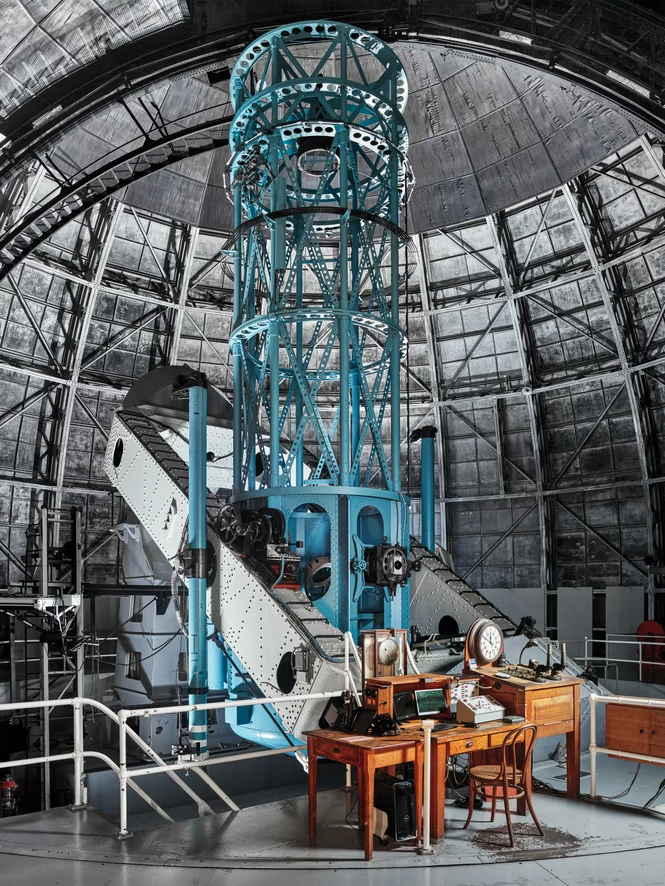

Americans have spent the past century and change building a series of colossal telescopes, each peering more deeply into the universe than the one before. Astronomers in London, Paris, and Berlin had surveyed large portions of the Milky Way during the 19th century, but they couldn’t be sure that anything existed outside it until an American astronomer named Edwin Hubble came along. In 1919, Hubble, then 29 years old, began using a new telescope, financed by a robber baron and constructed on Mount Wilson, a pine-studded peak just east of Los Angeles. Its 9,000-pound mirror was larger than any in Europe, and Hubble used it to look closer at the blurry blobs of light that his peers were then seeing all across the sky. Many believed that these mysterious “nebulae” were small clouds of stars nested inside our galaxy. Hubble pointed the telescope at the largest of them, and for 45 minutes, he let its light pile up on a glass plate coated in a photosensitive emulsion.

Today, it is the most cherished plate in a collection of more than 250,000 kept in a vault guarded by thick steel doors at the Carnegie Observatories, in Pasadena. I recently watched a latex-gloved Carnegie staffer tremble as he removed it from an envelope. In the image of the nebula on its surface, Hubble had marked a star that he had never seen before. He would later notice it flashing repeatedly, like a firefly, in super-slow motion.

This rhythmic flashing allowed Hubble to calculate the star’s distance from Earth, and he was jolted to find that it was not in our galaxy at all. The nebula hung in space an awesome distance beyond the Milky Way’s far edge, a galaxy unto itself. We now call it Andromeda, and we know that it contains more than a trillion stars. In the years to come, Hubble would find evidence of a dozen other galaxies that surround us. He discovered the universe beyond the Milky Way.

But only its local regions. In 1998, more than 25 years before Lystrup became the director of Goddard, she visited its campus as an undergrad. She remembers touring the control room for the first major telescope that NASA had placed outside the distortion of Earth’s atmosphere. By that time, the Hubble Space Telescope had been in orbit for less than a decade, yet it had already profoundly enlarged human vision. Like its namesake, the Hubble had run some long exposures in order to look deeper into our universe. During one 10-day stretch, it had stared directly at a single tiny pinhole of black sky and revealed it to be packed with thousands of galaxies. This image soon imprinted itself on the global collective consciousness. Ordinary people from nearly every country on Earth saw it, and came to understand something about the nature of existence at the largest scale.

In 2021, the James Webb Space Telescope launched, and once in space, it unfolded a gold-coated primary mirror nearly three times as large as the Hubble’s. Astronomers have since used the Webb to see clear back to the beginning of time. They have watched the first galaxies forming. The Webb cost nearly $10 billion and took more than a decade to build. But once in orbit, telescopes are relatively cheap to maintain. After 36 years, the Hubble is still doing science. And if the Webb is allowed to continue operating, it, too, will be able to keep straining to see the first stars that flared into being after the Big Bang, until its fuel runs out around 2045.

When Lystrup received the first leaked version of Trump’s budget request in April, she was shocked to see that he had zeroed out funding for the Roman. It was almost fully assembled in Goddard’s clean room, nearly ready to launch. In Trump’s final budget request, in June, the Roman was spared, but funding for the Webb was cut back severely, even though the telescope has a different function; the Roman’s shallow widescreen vistas are meant to complement the Webb’s deeper, narrow stares into the universe. According to a senior scientist who was closely involved with the Webb, the cut would put it on “life support.” Without enough staff to help keep it stable and to calibrate its data, the vision of the world’s most powerful telescope would be effectively blurred. And its lifespan would be shortened, perhaps by as much as a decade.

Trump took aim at another telescope too, perhaps the most ambitious in history. For decades, NASA has been working toward a giant instrument custom-made to look for life around the 100 nearest sunlike stars, including many that we could one day reach with a probe. The Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) would zoom in on the most Earthlike planets that orbit them. In their atmospheres, the telescope would look for the gas combinations that appear only when life has taken hold, be it microbial slime or coral reefs and rainforests, or something far stranger. To do all of this, in orbit, the HWO will need to achieve an unprecedented state of Zen stillness. NASA had hoped to get it into space in the late 2030s, but Trump’s budget request called for an 81 percent reduction in its funding. That cut could push its launch, and any discoveries it makes, beyond the lifetimes of many people alive today.

[Read: America is killing its chance to find alien life]

As Lystrup looked over these and other budget details, she got a sense of what the administration wanted for Goddard. Among other things, its workforce was to be halved. After the request leaked, people there were openly crying in the halls. Lystrup was asked whether NASA was even going to do science anymore.

On June 16, Lystrup held an emotional town hall. She explained that the budget request had called for Goddard to become much smaller, almost immediately, with deeper cuts in the years to follow. “I think it is very clear that this administration is looking to significantly shrink the science organization at NASA,” she said. The next day, she heard that leaders at NASA headquarters believed that she hadn’t been sufficiently supportive of the president’s budget. She heard that there was talk of retribution, and worried that she might be fired. An official in NASA leadership called and asked her to reflect on whether she’d spoken too frankly, in a way that might be interpreted as unaligned with the administration’s goals. Lystrup did that, and concluded that Goddard’s staff had deserved a frank account of what was happening. She decided to resign.

At the start of Lystrup’s tenure, Goddard’s workforce had been approximately 10,000. When she left, it was just 6,500. Most of the losses had come in the first seven months of Trump’s second term. The teams of scientists and engineers that built America’s great space telescopes were being scattered. Staffers were told not to hold farewell gatherings during work hours, because they had become too numerous.

A full accounting of Trump’s assault on American science will have to wait for historians, and we cannot yet say what the worst of it will be. His appointment of a charlatan to lead the country’s largest public-health agency may well prove more detrimental to Americans’ daily lives than anything he does to NASA. But his attempt to ground the agency’s science missions suggests a fundamental change in the country’s character, a turning inward. America’s space telescopes and probe missions have not only torn the veil from nature. They’ve had an ennobling effect on American culture; to the world, they’ve projected an elevated idea of Americans as competent, forward-looking adventurers, forever in search of new wonders.

NASA is as prone to bloat as any other government agency, and previous presidents from both parties have tried to trim its science budget. But never so severely. They understood that although private companies can do some of the things that NASA does, they don’t fund ambitious missions that have no purpose apart from answering our most profound cosmic questions. Neither SpaceX nor Blue Origin has done so once.

Trump still has another three years to shape NASA in his unscientific image. Rank-and-file scientists at the agency aren’t sure what to make of his November renomination of Jared Isaacman as administrator. When the president first tapped the billionaire astronaut during his transition period, they felt cautiously hopeful. Isaacman has claimed to support science missions, and once even offered to personally fund and fly a mission to try to extend the Hubble Space Telescope’s lifespan. But after Trump withdrew his initial nomination, it’s unclear how much groveling Isaacman had to do to regain it. When Isaacman was asked about NASA’s funding of science at his second confirmation hearing, in December, he did not distance himself from Trump’s priorities. He said that he supported the president’s efforts to reduce the deficit.

Congress will have the last word on NASA’s budget, if its members are able to pass one. A proposed budget from the House of Representatives had called for an 18 percent cut to NASA’s science missions, but the Senate’s much smaller cuts look likely to prevail. In the meantime, NASA staffers are still in a terrorized state. Existing missions have been destabilized by the mass departures. Planning remains difficult, if not impossible. Whatever Congress passes, Trump could repeat his budget-request shenanigans in February, and every year of his term thereafter. He could keep the agency in a state of dysfunction until he leaves office.

NASA’s most ambitious science missions are particularly vulnerable to this kind of sabotage. They have to be planned on time horizons that transcend a single presidential term. They require intergenerational vision.

Before I left JPL, I visited its Mission Control center, the darkened, glass-walled room where NASA staffers exchange messages with every American spacecraft that has flown past the moon. Inside, rows of workstations were lit up by blue neon. They faced two large monitors displaying the status of telescopes and robotic probes all across the solar system. Near the back, Nshan Kazaryan, a 24-year-old engineer, sat in a swivel chair under a sign that said Voyager Ace.

The Voyagers, 1 and 2, were launched in 1977, before either of Kazaryan’s parents were born. By 2018, both probes had left the solar system. If you picture the sun traveling around the Milky Way’s center, in its stately 230-million-year orbit, Voyager 1 and 2 are out ahead of it, the most distant human-made objects from Earth. On his screen, Kazaryan pointed to data that he had just begun receiving from Voyager 1, the farther of the two. To reach us, the data had traveled at light speed across a 16-billion-mile abyss for nearly a day.

A 64-year-old woman named Suzy Dodd quietly appeared behind me, wearing a button-down shirt patterned with spacecraft. In 1984, Dodd landed her first job out of college at JPL, helping the Voyager team prepare for an encounter with Uranus. Now, more than four decades later, she’s spending the final years of her career leading the mission as its project manager. Dodd thinks of the Voyagers as twins that are slowly dying as they press on into the unknown. “They were identical at launch; they are not identical now,” she told me. Each has seven of its 10 scientific instruments turned off, but not the same seven. It’s as though one has lost its hearing and the other, its eyesight.

The nuclear-powered hearts that sit inside the Voyagers are decaying. They spend most of their energy on their transmitters, which must keep an invisible thread of connection with Earth intact across an ever-widening expanse. The remaining juice on Voyager 1 is only enough to charge up a tablet, but it has to suffice for a 12-foot-long spacecraft that needs heat to function in the interstellar chill. Dodd and her team will sometimes turn off its main heater so that the gyros can barrel-roll the spacecraft, to calibrate an instrument. They have to turn it right back on, or its propellant lines will freeze.

The Voyagers’ onboard computers have been continuously operating longer than any others in existence. There is always a little suspense when the Mission Control crew is expecting data, a fear that the long-dreaded day has come when none will come in. Kazaryan pointed at rows of values on his blue screen that were constantly updating. All of them were in white, he noted. “That’s what we’d like to see.”

One day in 2023, the values flashed yellow and red. There was a problem aboard Voyager 1, and no obvious fix. Only four full-timers are staffed on the Voyager mission now, but thousands of people have worked on it previously. “Many of them are no longer with us,” Dodd said. But the living alumni are a rich repository of mission lore: They went into their garages or storage units and rummaged through old boxes of Voyager paperwork. The archival memos that they dug up helped the team fix the anomaly. Voyager 1 was able to keep describing the alien properties of the interstellar realm. It can keep counting the charged particles that fly in from exploding stars on the other side of the galaxy. It can continue to give us a sense of the magnetic fields out there.

Even before the Voyagers left the solar system, they had blessed us with a fresh vision of our immediate cosmic environment. They discovered Jupiter’s rings and hundreds of erupting volcanoes on its moon Io. They revealed the cracking patterns that cover icy Europa, another moon, hinting at its ocean. They caught Saturn’s moons creating braiding patterns in its rings. Their close-ups of Uranus and Neptune were beamed to screens all around the world. Before crossing the barrier that divides the sun’s sphere of influence and the rest of the galaxy, Voyager 1 turned its camera back toward us and snapped a picture of Earth suspended in a sunbeam.

Then it went rushing away. An astrophysicist recently used a computer simulation to calculate its future trajectory, and determined that it has some chance of being ejected into intergalactic space when the Milky Way and Andromeda merge, billions of years from now. It could be the final surviving artifact of human existence. Even if the Voyagers go dark tomorrow, they will long testify to the reach of America’s scientific imagination, and the daring of its engineers. NASA’s exploration of the solar system may be what most recommends our civilization to the future.

Dodd told me about a letter she’d received from a 4-year-old girl. Inside the envelope, the girl had tucked a drawing of a new mission, Voyager 3, with several instruments bolted onto the probe, including a vacuum for retrieving interstellar dust. I asked Dodd why there hasn’t yet been a Voyager 3. She disputed the premise. The more recent probes that NASA has sent to Jupiter and Saturn are the Voyager mission’s children, she said. The spacecraft that is now on its way to look closer at Europa’s ocean is its grandchild. That lineage is now endangered. But Dodd hopes that it will continue. She hopes that the Voyagers’ great-grandchildren will fly faster, and one day streak by their ancestors out in interstellar space, on their way to other stars.

This article appears in the February 2026 print edition with the headline “Grounded.”

The post Inside Donald Trump’s Attack on NASA’s Science Missions appeared first on The Atlantic.