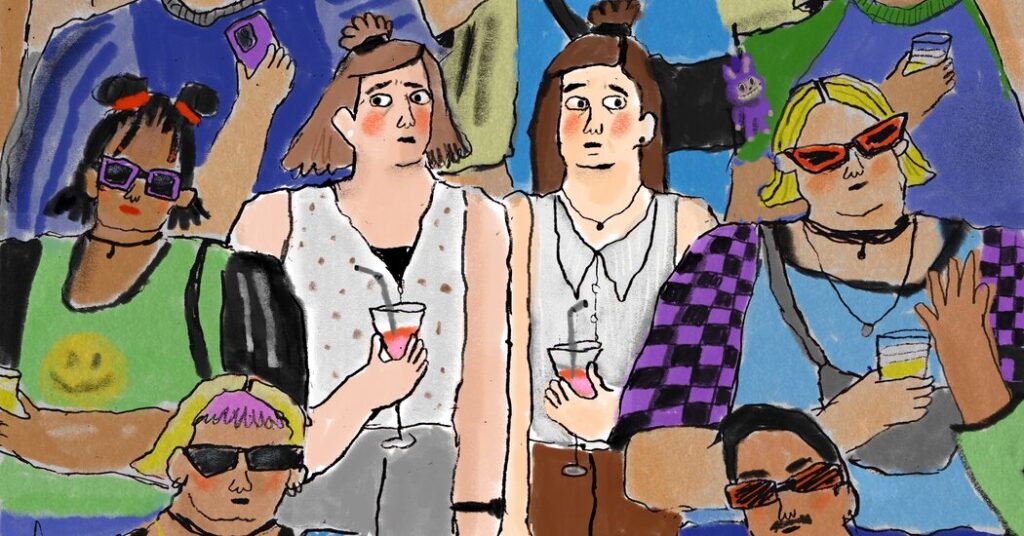

A few weeks ago, a group of girlfriends and I were messaging about their upcoming trip to visit me in New York City. The topic turned to what they should wear to look cool at a series of scene-y downtown bars they had heard about online and planned to visit. This was a group of stylish women who had worked in fashion and media and normally had no trouble dressing for the occasion. But, having been to some of those spots and borne witness to the Gen Z trends I saw there, I had to be the bearer of bad news: There was nothing in any of our wardrobes that would look cool. Every young, hot girl dresses like Adam Sandler now: cargo shorts, oversize graphic T-shirts, wraparound sunglasses. Our Rachel Comey blouses weren’t going to cut it. No matter how much we tried, we were going to look washed-up.

The moment crystallized a sentiment many millennials have been feeling recently: that 2025 is the year we officially got old. This reality has been creeping up for a while now, but it’s become impossible to deny it any longer. The youngest of our cohort are about to turn 30, and the oldest are pushing 45, meaning that we’re all now inhabitants of the life phase that the psychologist Clare Mehta has called “established adulthood,” a demanding period that can involve juggling careers while caring for kids and aging parents.

Our generational avatars are doing corny, middle-aged things: Lena Dunham wrote a “Why I Broke Up With New York” essay; Taylor Swift got engaged and wrote a song about her fiancé’s reliable penis; Ryan from “The O.C.” made a documentary about the dangers of crypto. If one of our generation’s athletes is still dominant, he’s considered a medical marvel. We are old enough to experience a type of millennial entropy in which our icons collapse in on themselves. (See: Justin Trudeau and Katy Perry’s relationship.) We were the generation that first embraced mining every aspect of our inner lives for content, but we don’t even enjoy posting on social media anymore. Thanks to medical miracles like Botox and Mounjaro (and Solidcore reformers), millennials are still physically hot, but culturally, our goings-on provoke less fascination, less hand-wringing, less societal anxiety. When they talk about young people, they aren’t talking about us anymore.

Every generation gets its turn to lament its cultural obsolescence, but that stings especially for millennials. Coming of age on the internet made us singularly self-obsessed, or so the think pieces proclaimed: an army of more than 70 million narcissists raised on BuzzFeed quizzes and Four Loko, unable to figure out adulting and demanding a gold star every time we did a thing. But now it’s Gen Z and Gen Alpha that are making marketing departments quake. The timing of the Covid-19 pandemic made our exit from the cultural stage feel even more dramatic: Still sprightly when we went indoors, we exited with creaky knees, to a world being remade in Gen Z’s image.

How do we know we’ve gotten old? Sometimes a Zoomer will just come out and say it to our faces, as when my 35-year-old friend recently went to her 23-year-old co-worker’s concert and was asked if she was “a friend of his mom.” Another friend received blank stares from his young co-workers when he said he planned to go as Fred Durst for Halloween.

Mostly, though, the demarcation of our generational divide happens in a place that used to be ours to define: online. The internet, once our safe space, has increasingly become hostile territory. Millennials’ very existence has become so embarrassing to Gen Z-ers that they’ve coined a phrase for it: “millennial cringe.” This cringiness includes the kinds of socks we wear (ankle-length, not crew) and the awkward pauses in our videos, the fact that we end our messages with “lol” and overuse the laugh-cry emoji and how we know which of our friends are Gryffindors. We are now unc and frequently also washed.

This year, long-simmering tensions spilled over into open warfare. Millennials lashed back at Zoomers — who are reportedly partying less, hooking up less and spending less time hanging out — as sexless, illiterate hermits wasting their youth brain-rotting on TikTok and getting radicalized by white nationalist streamers. If you are reading this as a Gen Z-er, this is probably already all obvious to you. If you are reading this as a Gen Z-er, however, it is also incredible that you are reading at all.

Much of the millennial alarmism about Gen Z-ers (“easily offended, lazy and generally unprepared” snowflakes, reports The New York Post) is word for word what older generations said about us. Having lived the past few decades under the microscope, millennials should recognize that generational hostility is often just a way to avoid grappling with change by blaming young people, who are actually suffering the brunt of it.

We know the reason we couldn’t buy houses wasn’t that we were buying too much avocado toast, much as things that worry us about Gen Z-ers are a result of the world they’ve inherited. In fact, we have a lot more in common with the next generation than we think. We both came of age amid major economic shocks and inherited the same polarized and dysfunctional politics. In a 2025 Deloitte survey, 48 percent of Gen Z-ers and 46 percent of millennials said they felt financially insecure, and 74 percent of Gen Z-ers and 77 percent of millennials expected artificial intelligence to reshape the way they do their jobs.

Millennials have more debt, marry and have kids later and buy homes later (if we’re even able to) than our parents did. Many of the traditional markers of middle-class adulthood — family trips to Disneyland, professional fulfillment — are far out of reach for our generation. This can make us feel “younger than every middle-aged cohort before us,” as Emily Gould put it in a recent New York magazine essay about elder millennials.

Maybe that’s why many of us try so hard to cling to our youth: We are staring down the barrel of old with all of the baggage and none of the benefits we were taught to expect. But all of this should make us more sympathetic to the next generation, not less. We can simultaneously feel horrified by TikTokers in their tiny sunglasses and realize that we’re in this together — that the intersecting political, financial and technological crises of today are going to affect us all.

While millennials may no longer control online discourse or be able to recognize more than 20 percent of the Coachella lineup, our generation is increasingly taking up the mantle of institutional power. After calling for an end to gerontocracy for years, we’re finally starting to see it happen. We have a millennial vice president, a millennial mayor-elect of New York City and a millennial Vogue editor. Millennials are entering the C-suite (passing over poor Gen X once more) and redefining family life with gentle parenting strategies. Our task now is figuring out how to age gracefully into this next phase of the generational life cycle, even if we may not always agree with the kids coming up from behind.

The figures who have always had the most cross-generational appeal aren’t the ones who turn into bitter old grumps. Rather, it’s the people who are willing to evolve and remain curious about what younger people care about now. Think: David Bowie’s early recognition of internet culture. Or more recently, Charli XCX in her “Brat” era, whose lo-fi aesthetic and collaborations with young artists like Billie Eilish and Addison Rae spoke to the mood of Gen Z — even when her lyrics evinced quintessentially millennial concerns about fertility and finding the best bathroom to do coke in.

In turn, Gen Z-ers are engaging with and appreciating elements of the millennial canon in ways we didn’t always ourselves, whether it’s watching “Girls” with admiration instead of anxious discourse or lining up to see Caroline Polachek and Mac DeMarco in concert. Our generation gave the world some good stuff (“Superbad,” going-out tops, 2000s Williamsburg), and some bad stuff (Theranos, mustache finger tattoos, 2020s Williamsburg), but it’s not always up to us which of our cultural touch points stand the test of time. While it can be annoying seeing younger people claim your icons — especially if you’re competing with them for concerts on Ticketmaster — reinterpretation is what keeps culture alive.

The writer Anne Helen Petersen rightly says that our generation should be alert to avoiding the cardinal sin of our boomer forebears, in which we “climb the ladder to relative stability … and then pull it up behind us.” While plenty of our peers are engaging in the time-honored tradition of becoming rich jerks, she sees a worrying solipsism even among those who weren’t employees with equity at ride-sharing start-ups in the mid-2000s. “We became cleareyed about all the ways society is set up to fail so many of us,” she writes, just at the time that we began feeling “too exhausted, too old, to fix things.”

Yet some of our generation’s most influential political leaders are those who have figured out how to speak to what the next one cares about. JD Vance and Zohran Mamdani, in diametrically opposed ways, are speaking to young voters’ economic anxieties by promising a change from boomer politics as usual. Mr. Mamdani, soon to be New York City’s first millennial mayor, won the election decisively by taking home 78 percent of the under-30 vote. He did this in part by engaging with young voters’ concerns around housing and affordability while embracing tools like short-form video in a way that felt organic instead of pandering. But he also owned his millennial cringe: Much of his early campaign — a 33-year-old dude, standing on a street corner with less than 1 percent in the polls, asking random people why they voted for President Trump for a YouTube video — was objectively cringey. There was something about Mr. Mamdani’s goofy sincerity that younger voters appreciated.

Gen Z-ers might wince at our earnestness, but they also value authenticity. Millennial cringe is somewhat synonymous with millennial optimism, that earnest (and, yes, sometimes naïve) feeling that better things are possible. But it’s worth holding on to — as long as we can divorce it from the clap-stomp music that so often accompanied it.

Anna Silman is a freelance writer and editor based in New York.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post This Is the Year Millennials Officially Got Old appeared first on New York Times.