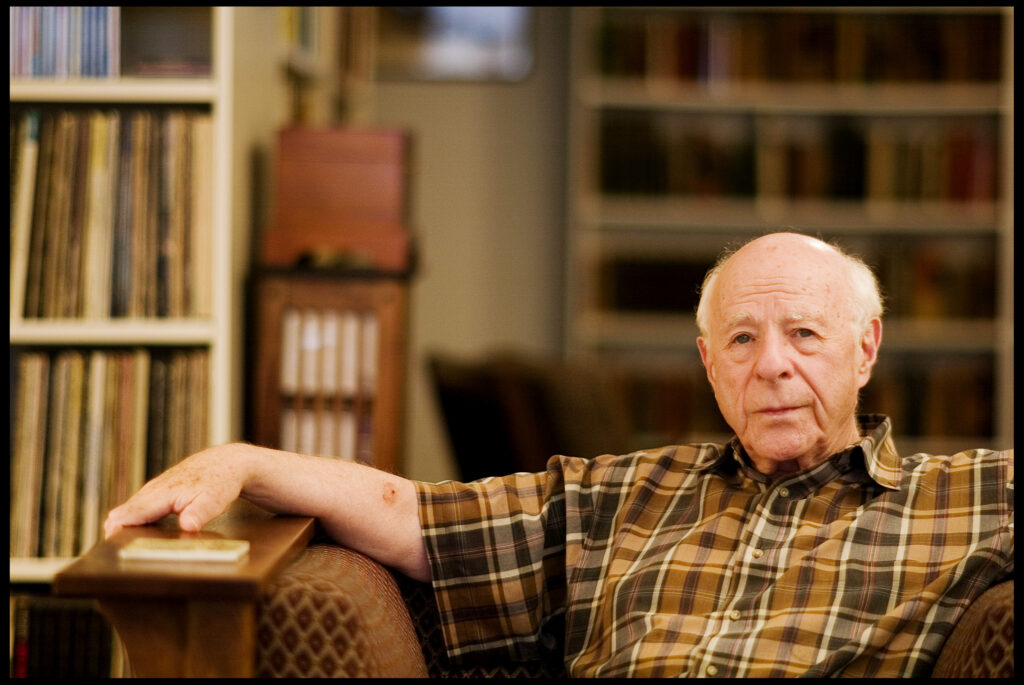

Norman Podhoretz often credited a public school teacher, Mrs. K, who heard the Brooklyn boy’s heavy accent and insisted that he take speech lessons. These lessons helped him be taken more seriously as he attended, on scholarships, institutions of higher learning: Columbia University, where he studied with Lionel Trilling, and Cambridge University, where he learned from F.R. Leavis.

With that grounding, Podhoretz, who died Tuesday at age 95, went on to become one of America’s leading public intellectuals, a writer and editor of enormous influence in the latter half of the 20th century. Not least among his accomplishments was serving as an inspiration to many disaffected 1960s liberals in their movement from left to right.

Podhoretz quickly learned, as a young man, that philosophical fights mattered greatly among the circle he aspired to join, known as the New York intellectuals. When he wrote a negative review of Saul Bellow’s 1953 novel “The Adventures of Augie March,” a friend of Bellow’s told Podhoretz, “We’ll get you for that review if it takes 10 years.” A bewildered Podhoretz later recalled: “I was 23 years old. I go, ‘What?’”

He didn’t stay bewildered for long; he learned to fight and feud with the best of them. In 1972, the New York Times ran an exhaustive article detailing one of those feuds, between Podhoretz and New York Review of Books co-founder Jason Epstein. The subtitle of Podhoretz’s 1999 memoir, “Ex-Friends,” called out former pals by name: “Falling Out with Allen Ginsberg, Lionel and Diana Trilling, Lillian Hellman, Hannah Arendt, and Norman Mailer.”

The most important development in his life — and a key one in America’s intellectual history, for that matter — was his being named editor of Commentary magazine in 1960. Only 30 at the time, Podhoretz made it into a must-read for anyone interested in engaging with the most serious political, cultural and intellectual issues of the day. Commentary’s personality reflected that of its editor. As the formidable literary critic and academic Ruth Wisse once wrote, “Norman Podhoretz and his writers fearlessly attacked their subjects, wrestling them to the ground like street fighters, I thought, without ever having seen a fist fight except in the movies.”

That combination of pugnacity and erudition served him in good stead as he migrated from liberalism to a more conservative outlook, increasingly disillusioned by the anti-Americanism of the New Left. He and his wife, writer and editor Midge Decter, in the early 1970s had helped form the Coalition for a Democratic Majority, which tried, and failed, to keep the Democrats from drifting leftward.

Undaunted, he moved toward what came to be known as neoconservatism, advising Republican Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, who awarded Podhoretz the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2004.

In Commentary, Podhoretz published many writers who had followed a similar philosophical path, helping launch the careers of Reagan administration stalwarts William Bennett and Jeane Kirkpatrick. Kirkpatrick’s 1979 Commentary piece, “Dictatorships & Double Standards,” was read by Reagan and led to her appointment as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Her article was a classic of the magazine under his editorship, offering a provocative, powerfully argued message (heavily edited in the Commentary style): that authoritarian regimes could evolve into democracies, but totalitarian ones couldn’t.

Commentary under his guidance brimmed with similarly influential articles, but two particularly memorable ones were Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s “The United States in Opposition” and Podhoretz’s own “My Negro Problem — and Ours,” a searing exploration of race based on his experiences growing up in Brooklyn. That piece, naturally, grew out of a literary fight: an argument with James Baldwin after Baldwin told Podhoretz he’d given an article to the New Yorker that he had promised to Commentary. Podhoretz unloaded on Baldwin, prompting Baldwin to suggest that Podhoretz write up his grievances, which he then did.

Podhoretz also wrote a dozen books, among them four memoirs of his eventful life, filled with delicious tales of a now-vanished New York intellectual world. The most notorious of these memoirs was his first, “Making It” (1967), revealing the extent of his ambition to succeed in the literary world. Friends advised him not to publish it; others dropped him after it came out. Reviled at the time, “Making It,” was reissued by NYRB Classics in 2017, prompting Podhoretz to say, “To have gotten this imprimatur from the New York Review — for them to reissue it and call it a classic — was not something I ever expected to live to see.”

He didn’t write short. When you saw an issue of Commentary that had an article by Podhoretz in it — something that happened a remarkable 145 times — you knew it was time to settle in with a cup of tea or coffee and enjoy the ride. The writing was terrific: propulsive and passionate, filled with allusions that you were expected to understand.

He cared about so many things: about literature and America, Israel and intellectuals, and the threats of terrorism, communism and antisemitism. You felt the depth of his passion for each.

Some of his insights have only gained in relevance. In 1971, speaking in New York, Podhoretz noted a change in America in the years following Israel’s success in the Six-Day War of 1967. “Anti-Zionism,” he said, “has served to legitimize the open expression of a good deal of antisemitism which might otherwise have remained subject to the taboo against antisemitism that prevailed in American life from the time of Hitler.”

It’s tempting to say he had no idea what was coming, but this was Norman Podhoretz — of course he knew what was coming. He was a master of reading signs of political and cultural change, and advocating for the best path to follow in the country he loved.

Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Ronald Reagan Institute and the author, most recently, of “The Power and the Money: The Epic Clashes Between Commanders in Chief and Titans of Industry.”

The post Norman Podhoretz, an intellectual powerhouse of the postwar era appeared first on Washington Post.