A’ja Wilson is a picture of sheer joy and utter domination. As she approaches the vehicle that will drive her and her Las Vegas Aces teammates up the Strip for a parade feting the team’s third WNBA title in four years, her right hand grips a cocktail glass containing a pink slushy adult beverage, a pink Stanley tumbler for hydration and libation, and a pink tambourine. As a child, Wilson would shake this instrument during sermons in her South Carolina Baptist church. Today she’ll rock it on the bus while waving at delirious fans. Aces win. Again. Amen.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Covering Wilson’s left hand is the golden gauntlet worn by Thanos, the Marvel supervillain. Under each of the six Infinity Stones that control the universe, Wilson, the 6-ft., 4-in. superstar, has written one of her season’s honors: Scoring title, her second; 5K—in June she became the fastest player in WNBA history to reach the 5,000-point milestone; DPOY, for defensive player of the year, her third; MVP, her record fourth; Finals MVP, her second; and Champ, her third. She’s the first player, in WNBA or NBA history, to win a championship and be named Finals MVP, league MVP, and Defensive Player of the Year in the same season. And she’s one of just four players in either league to win four MVP trophies before the age of 30, the others being Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and LeBron James. “I’m waiting on them to call for the Academy Award and the Emmy,” quips her father Roscoe.

“When you’ve collected everything, that’s Thanos,” says Wilson, 29, during an interview in a New York City hotel room, about a month after the parade. “And this year, I collected everything. I don’t really talk much sh-t. I mean crap. I kind of let my game do it. This was my biggest moment of doing it, because no one’s ever done what I’ve done. And I think people really needed to understand that.”

She breaks down her parade outfit too: The front of her black T-shirt paid homage to Michael Jordan, mimicking the design he wore to the parade celebrating his own third championship, in 1993. The back said re’gression year, a play on something sports podcaster and writer Mark Gunnels posted on social media when the Aces struggled earlier in the season: The A’ja Wilson regression was something I didn’t expect to see this season. “That’s when I was like, ‘Oh, people are really playing on my name,’” says Wilson. “But my regression leads to a championship.”

Click here to buy your copy of this issue

On Oct. 8, Gunnels posted that Wilson “is still the best player in the world with a real argument to be the GOAT.” She reposted his message the day after the Aces won the title victory with a GIF of Big Boi saying, “I know that ain’t who I think it is” from the 2006 movie ATL.

“I could not,” says Wilson through laughter, “not be petty.”

Judging by Wilson’s air guitaring a Nirvana song at the postparade rally and dancing onstage with Crime Mob, one of her favorite hip-hop groups, pettiness—at least her version of it—has taken an exuberant turn. And why not? After all, these Aces were never supposed to be here. More than midway through the season, the team was hovering at .500. But then Vegas won its last 16 regular-season contests and survived two tight playoff series before sweeping Phoenix in the Finals. “Sometimes you’ve just got to get knocked down to get built back up,” says Wilson. “I think 2025 was a wake-up call that I needed, to let me know that I can’t be satisfied with anything. There’s somebody out there that’s going to try to take your job. You need to make sure you’re great at it, every single day.”

Perhaps, even, the greatest.

“I’ve been the GOAT since 1996 in my house,” says Wilson, playfully flashing her tongue—just like she did after hitting an instantly iconic buzzer beater in Game 3 against the Mercury. She turns contemplative. “I think I’m on my way there,” she says. “I’m making it real hard for people to chase after me. That’s what it means to be the GOAT.”

Her rocket-ship run comes at an opportune time. In 2024, Caitlin Clark’s rookie season helped the WNBA hit milestone TV and attendance figures. But Clark’s emergence created a toxic, racially divisive narrative that she was almost singularly responsible for salvaging a league whose foundation had been built by a mostly Black player base. This storyline bothered Wilson, who in 2024 earned her third WNBA MVP award and her second Olympic gold medal in Paris, where she was named tournament MVP. “It wasn’t a hit at me, because I’m going to do me regardless,” she says. “I’m going to win this MVP, I’ll win a gold medal, y’all can’t shake my résumé. It was more so, let’s not lose the recipe. Let’s not lose the history. It was erased for a minute. And I don’t like that. Because we have tons of women that have been through the grimiest of grimy things to get the league where it is today.”

The 2025 WNBA campaign provided a measure of vindication for many players. Despite Clark’s missing most of the season with an injury—something Wilson, to be clear, did not cheer—viewership for both the regular season and postseason was up 5% to 6% on a per-game average across ESPN networks. “Sometimes you need a proof in the pudding,” says Wilson. “The biggest thing for us, and why I was so happy, is that we continue to rise to the occasion. This was just a matter of time for us to really bloom and blossom. Because we have been invested in each other and our craft for a very long time. It was just like, ‘They’re going to pay attention.’”

These tailwinds offer players some leverage as they negotiate a new collective-bargaining agreement. The current agreement was extended for a second time on Nov. 30 and is now set to expire on Jan. 9; failure to meet a resolution with the league could cause a lockout and stall the WNBA’s momentum. “All of us are going to be at the table,” says Wilson, “and we’re not moving until we get exactly what we want.”

Wilson, a seven-time All-Star, has positioned herself as an ideal leader in this pivotal moment in women’s sports history. She is an effervescent WNBA ambassador, who in recent weeks has been everywhere, finally getting her due. The Jennifer Hudson Show, The Tonight Show, Good Morning America, Not Gonna Lie With Kylie Kelce, Hot Ones. She’s got endorsement deals with Google, Chase, PepsiCo, and AT&T, among others. Wilson appeared courtside to support her boyfriend, Miami Heat All-Star Bam Adebayo, and hugged Beyoncé at a Formula One race in Vegas. Cardi B name-dropped her in her summer hit, “Outside.”

“She’s a culture shifter,” says actor Gabrielle Union. “She forces the world to take notice without scandal or gimmicks, just excellence without trying to be perfect.” LeBron James recalls seeing his 11-year-old daughter watching Wilson on TV recently. “I realized her greatest impact isn’t what I see, it’s what Zhuri sees,” he says. “A’ja Wilson is the definition of female Black excellence, and I am so grateful she is giving my daughter the kind of inspiration I got from Michael Jordan and Ken Griffey Jr.”

While refusing to relinquish her supremacy on the basketball court, Wilson has managed to extend her power far beyond the field of play, a trick that only a precious few athletes can pull off. LeBron. Ali. Serena. A’ja. “A’ja isn’t a rising star anymore,” says philanthropist Melinda French Gates, whose publishing imprint released Wilson’s best-selling memoir, Dear Black Girls, in 2024. “She’s at the center of her own solar system.”

Wilson is not exactly living out an early childhood dream. Her general stance as a kid growing up near Columbia, S.C., was: anything but basketball. Though Roscoe had played professionally abroad and wanted her to try the sport, Wilson sampled a host of extracurriculars—piano, ballet—before taking up the game. “The people that I saw play it in my town, they were just never good-spirited people,” she says. “They always came off as the bullies and the cool girls. So I blamed it on the sport.”

Wilson was introverted, which she attributes in part to an incident she details in her memoir. In fourth grade, one of her classmates invited her to a slumber party but told Wilson that she might have to sleep outside, because her father didn’t like Black people. “It made me realize I was different,” she says. “I wasn’t really thinking different as in just skin color. It was like, ‘It’s something about me you don’t like, right?’ And that was the part that I really couldn’t register.”

During those formative years, Wilson also struggled with a learning disability that affected her mental health. “It was just a bummer,” she says. “Like, ‘Dang, I worked so hard to get this right, I know the information, but I just cannot translate it. If I just had a normal brain, I could have gotten that.’” She was diagnosed with dyslexia at 16.

Embracing these differences, Wilson says, taught her to take on future challenges. And basketball built confidence. By the time she was around 12, Roscoe was talking her up to South Carolina head coach Dawn Staley. He was confident she would hit a growth spurt. And her rigid manner of organizing her toys—teddy bears lined up from biggest to smallest, Beanie Baby at the end—led him to believe she’d have the discipline and attention to detail needed to improve at a game she was just beginning to learn.

Wilson attended a South Carolina hoops camp. “We were highly anticipating Roscoe’s vision,” says Staley. “And it was far from it. She didn’t even make the good gym. You have good gyms and bad gyms. She was definitely in the babysitting gym.”

“She was trash,” says Roscoe. “Deep trash.”

But Roscoe was right about one thing: Wilson was willing to work. He put her in a weighted vest for training sessions and made her dribble a 5-lb. ball. “A lot of times, we would have silent car rides home,” says Wilson. “My mom’s just like, ‘What’s happening with my home? No one’s eating dinner.’” But as she started to taste success, she bought in. A travel-team coach, Jerome Dickerson, would call on South Carolina football players to guard her in practice. “I never had somebody that had that look,” says Dickerson. “‘No matter what you throw at me, Coach Dick, I’ll be able to handle it. No matter what you put on my plate, I can eat.’”

She became the top high school recruit in the nation but stayed local for college, choosing South Carolina. Staley, however, gave Wilson a hard time in practice for “blending,” or playing down to the competition and failing to stand out. When Wilson and I meet for our second extended conversation—where she orders a breakfast of flaxseed pancakes and sausage—I mention that word to her, and she winces. “It was sooooo aggravating,” says Wilson. “I’m just like, ‘Lady, what do you mean? Do you not know who I am? I don’t blend anywhere.’”

In one practice, after Wilson failed to touch the ball during multiple possessions, Staley told her to stand on the side with the walk-ons. An assistant coach asked if Wilson could return; Staley said no, and Wilson told the assistant no problem: she’d had enough of Staley’s antics anyhow. “That was one of our biggest fights,” says Wilson. “Because I was just like, ‘No, I’m not going to let you win.’ At the same time, I was like, ‘Damn, I was blending.’”

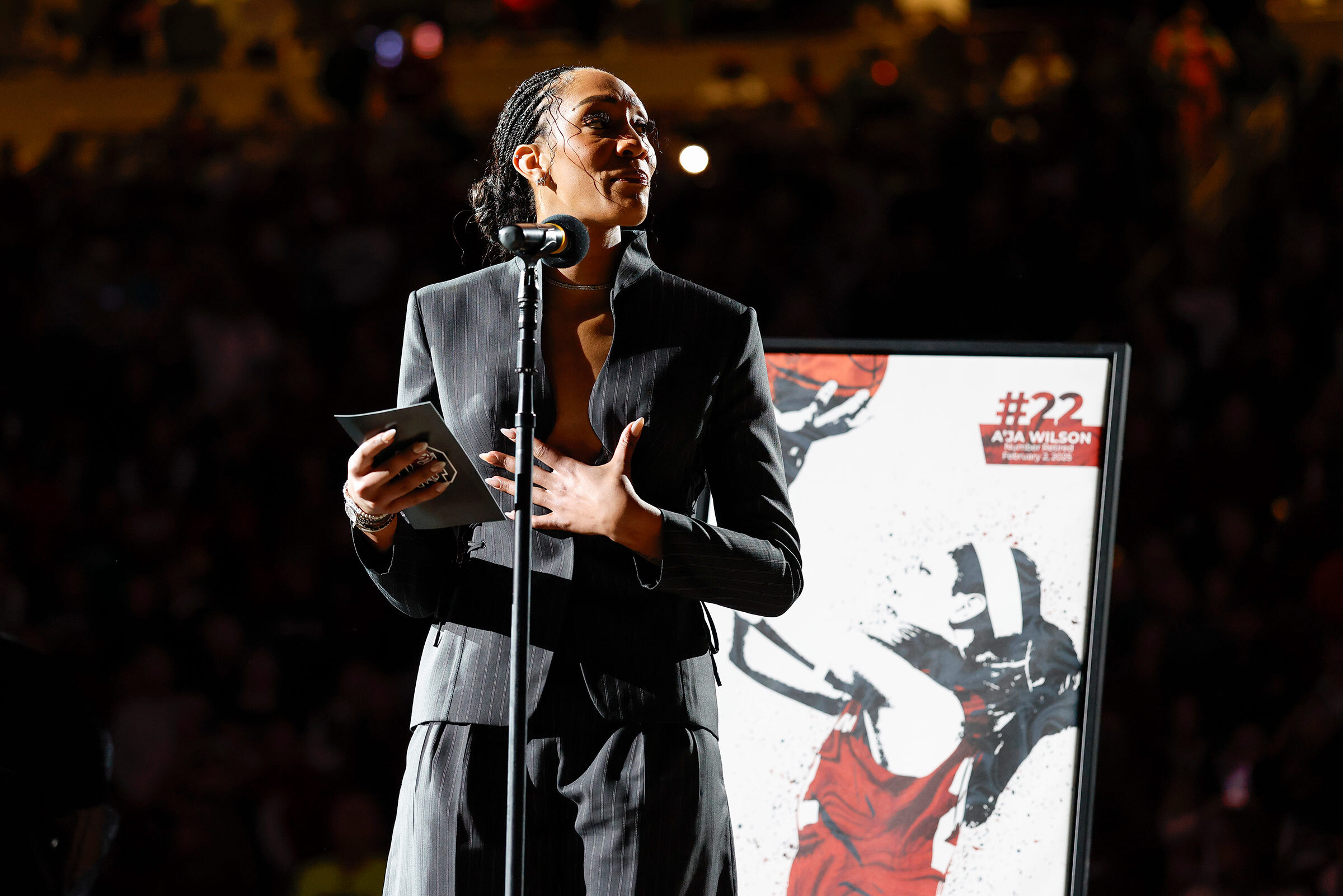

Staley’s voice remains in Wilson’s mind. I’m blending, she’ll tell herself during games. She only checks her phone at halftime for Staley’s messages. You’re blending, the Gamecocks coach tsk-tsks her. Wilson led South Carolina to the school’s first national championship, in 2017, and was named Most Outstanding Player at the Final Four. Less than four years later, the school installed a bronze Wilson statue on its campus. At the commemoration ceremony, Wilson noted that her late beloved grandmother, Hattie Rakes, couldn’t even walk on the university’s grounds in the segregated South.

The Aces took Wilson with the top overall pick in the 2018 WNBA draft. By the end of the 2020 COVID bubble season, she’d won her first MVP. The Aces also made the WNBA Finals but lost to the Seattle Storm. Wilson felt like she had let everyone down. “That moment caused a lot of depression,” says Wilson. “I was anxious.” On a family vacation on Kiawah Island, she threw up in a car her father was driving. Roscoe pulled over; his daughter started hyperventilating. She was having a panic attack. “My body was like, ‘You cannot do it,’” says Wilson. “It was rebuking.” With the help of therapy and her parents, Wilson moved past this scary experience. Roscoe and Wilson’s mother Eva reminded her she wasn’t a failure: she’d have other chances to win a championship.

Before the 2022 season, the Aces hired Becky Hammon, a former WNBA point guard working as an assistant for the San Antonio Spurs, as head coach. During Hammon’s first meeting with Wilson, she borrowed from her mentor, Hall of Fame Spurs head coach Gregg Popovich. In 1997, Pop told his No. 1 draft pick, future five-time champion Tim Duncan, that he’d have to not only coach him hard, but coach him hard in front of his teammates. Hammon said the same thing to Wilson.

The Aces won back-to-back titles in 2022 and 2023. But a three-peat in 2024 was not to be—the New York Liberty bounced the Aces in the semis. Communication on that team, Wilson felt, had faltered. “We were all not saying stuff, because we were just like, ‘Ooh, we know that,’” says Wilson. “And so I told myself this year, ‘That’s not who I want to be. I want to use my voice.’”

The Aces needed it. They started the season 5-7, in a stretch that included a 27-point loss to an expansion team, the Golden State Valkyries. Wilson and Aces point guard Chelsea Gray sneaked into an empty room after the game and cried in each other’s arms. Not long afterward, Wilson called out Gray in front of the whole team for having fewer assists than her in several matchups. “It was like, ‘Aight, damn, A’ja, I got it,’” says Gray. Through June, Gray averaged 4.3 assists per game. From July through the end of the regular season, 7.1.

Things would get worse for Vegas before they got better. On Aug. 2, the Aces lost a home game to the Minnesota Lynx, 111-58, to drop to 14-14. “It looked like Minnesota took their soul,” says Hall of Famer Rebecca Lobo, an ESPN commentator. “Not only took it, but stomped on it.”

Wilson usually unpacks games on the car ride back from the arena. “Especially losses, I never like to bring that into my home,” she says. “My puppies don’t deserve that.” (At the time, Wilson had two dogs, Ace and Deuce; she got a third, Tre’, before winning this year’s title.) Wilson fumed in silence for a few minutes as Adebayo drove. Finally, he asked if she wanted to talk about it. She did. Most glaring to him, he told Wilson, was the team’s lack of fight. “I was just like, ‘That could be the least favorite thing you could have ever said to me,’” says Wilson.

She couldn’t get to sleep. Around midnight, she texted her teammates: If today didn’t piss you off or embarrass you, please don’t bother coming to the arena tomorrow.

Her phone started buzzing, with exclamation points, thumbs-ups, and hearts. “When I saw that, I was just like, ‘OK, we’re good,’” says Wilson. “If it had not been that, I would have went in there with smoke coming out my ears. I would have not been sleeping. I would have gone over to team housing. ‘Everyone, wake up. We need to go.’”

The Aces heard Wilson loud and clear. “She could have cursed us out. She could have went down the line on why each person is not playing well,” says Jewell Loyd, who joined the Aces this season from Seattle, where she won two championships. “That wasn’t the text message. It was definitely stern. But it was definitely hopeful.” Wilson ended her missive with: I love each and every one of you guys, and I trust y’all till the wheels fall off.

The Aces didn’t drop a game the rest of the regular season. In July, Hammon had asked the players to start creating their own scouting reports on opponents. “I wanted them to take charge of what they were doing,” says Hammon. At first, Wilson fretted. “‘Guys, did she just leave us?’” Wilson says. “When parents leave the kids home alone, you’re like, ‘Now what?’” But she soon relished this new responsibility. “She was coming into shootarounds with a laptop every day,” says Hammon.

Wilson came up with an accountability chart. Each player would set some goal in the game. Hers was often remembering to box out her opponent for rebounds. In one game, she failed to do so twice. Forward Kierstan Bell got in her ear. “A!!!” she screamed. “BOX OUT! THE CHART!”

Hammon’s player-driven scouting strategy, says Wilson, “brought us life.” In turn, they could enjoy their outside lives more. Wilson organized team Uno games and outings. In New York City, the Aces went to a place where you put on a hazmat suit and solve puzzles or get slimed. Before an August game in Phoenix, rookie Aaliyah Nye planned on spending her 23rd birthday watching Netflix in the hotel. Wilson gave her a choice: bowling or an escape room. She chose the latter. Then the players went out for Mexican food. “She didn’t have to do anything,” says Nye. “But she went out of her way. It’s something I’ll never forget.”

“You see the consistency of being unselfish,” says Loyd. “That’s the difference between the different leaders I’ve been around and studied and A’ja. Some do it because they want to have a track record to show the media. She does it because that’s just who she is.”

Wilson led the Aces into the playoffs, but in the first round, Las Vegas barely eked out a decisive Game 3 against Seattle. They then dropped their first semifinal game against the Fever, putting them in a dangerous hole. Vegas needed overtime to pull out Game 5. “We just wanted to take the long run leading up to the Finals,” says Wilson. “We took the long journey the whooooole year.”

Until the end. In the inaugural best-of-seven WNBA Finals, Las Vegas won four straight over Phoenix. Wilson averaged 28.5 points, 11.8 rebounds, four assists, a steal, and two blocks per game. Game 3 delivered her signature moment. With the duel tied at 88-88, the Aces called time-out with five seconds left. The players expected a Hammon special; their coach is known for drawing up clever plays involving misdirection and deceit. Here, she drew just one curved line, for Wilson, from the top of the key to the elbow—or corner where the foul line meets the painted area. “I’m looking at the play, like, ‘Where’s the rest of it?’” says Wilson, who had 32 points by then. “‘Beck, what else?’” That was it.

“She was cooking that game,” says Hammon. “And she’s the greatest player in the world.”

Wilson, who says she was “really nervous” but couldn’t tell her teammates, wound up positioning herself down low, on the block; Loyd set a screen to get her open on the elbow. Wilson knew she’d have trouble shooting over DeWanna Bonner, one of the league’s rangiest players. She dribbled to her left, but Bonner stayed with her. When she spun back to her right, she saw some daylight. Once she realized Alyssa Thomas—Bonner’s fiancée and teammate—was coming over to help, she felt better. She had a few inches on Thomas. “‘OK, I can see rim,’” says Wilson. “Here we go.” She let the fadeaway fly.

She doesn’t really remember what happened after the ball bounced around the rim before dropping in. “It wasn’t a swish,” she notes. “It was a funky fall.” But with just 0.3 seconds left on the clock, the game—and series—was essentially over.

Her parents sat in the stands, but only her dad saw the bucket. Eva had her head down. “I was praying for it to work,” says Eva. “Because I knew if it did not work, she was going to be devastated.”

“When you think about a lot of GOATs, they have those career-defining shots that solidify you as the best,” says Wilson. “I didn’t really have one of those. I had championships, yeah. But it was never really like a moment of like, whoooooooo. That’s why she is who she is. She’s exactly who she thinks she is.” Wilson’s using almost the exact language of a video put out by Nike after she was named MVP, in which narrator Sheryl Lee Ralph runs through her achievements and asks who A’ja Wilson thinks she is (“She’s a model and a role model … The nerve”).

The Game 3 buzzer beater finally gave her that moment, Wilson explains. “It was very GOAT-defining.”

In a stroke of good fortune for Wilson, photographer Stephen Gosling captured Wilson’s shot at a stunning angle. She’s releasing the ball over Thomas and Bonner, the Mercury faithful under the basket watching nervously. Above the backboard, the clock shows 2.2 seconds: Wilson has worn the number 22 since high school, when she decided she wasn’t quite good enough to wear 23 like Michael Jordan or LeBron James. The viral image called to mind a portrait of Jordan’s “The Shot,” from 1998. The camera caught Utah Jazz fans with their mouths agape, anticipating that Jordan’s end-of-game attempt would crush their championship hopes. (It did.)

Eva has already imprinted the photo on her phone case. Wilson plans to frame it; she wants to hang it up, next to a picture of her with Crime Mob, in a hallway for her future kids to see. “I don’t know where Bam is going to put his pictures,” says Wilson. “But those two are going to be up there.”

I tell her Staley wanted me to pass along a question: When are she and Bam getting married? “That’s the question I need you to deliver to him!” Wilson responds. “I hope I’m not wasting my time. I hope he’s not wasting his time.” Says Adebayo when I check in with him: “Y’all will know, because people are nosy and they’ll look at her hands. There you go.”

Wilson and Adebayo are excited about starting a family. “That is always a dream,” she says. “This is my life partner. Honestly, what on earth was my world before you? That’s how much he’s impacted my life, my family’s life.” Roscoe will call A’ja and ask for Bam. “I’m just like, ‘Hey dad,’” says Wilson. “‘Your blood daughter.’” She’ll text her mom some piece of info. “Bam already told me,” Eva replies. “I didn’t know I was outside the group chat,” says Wilson. “I thought we are all in this to-ge-ther.” Her preteen nephew acts sort of over Aunt A’ja. But he perks up around Uncle Bam. “I’m like, ‘You don’t know him,’” says Wilson. “‘He just got here.’”

Adebayo calls Wilson his best friend. “As the young people say, that’s ‘twin,’” he says. “That’s what makes it so great. We’re striving for the same thing. We want each other to be better. We want to make it easier on one another, and we want to do this together. She’s a strong Black woman, man, and she does it with so much grace and positivity.”

They’ve been dating for about four years, first connecting at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. While COVID restrictions prohibited athletes from exploring the city, the U.S. basketball teams could pass the time together in a hotel lounge, playing Uno and dominoes. “The best thing about our relationship, we started out as great friends,” says Adebayo. “We didn’t just jump to, ‘Hey, what’s up? You and I will make a great thing.’ Nah, we really eased into this.” Given their high profiles, Wilson preferred that their relationship stay private until she and Adebayo grew more comfortable with each other. “We’re still trying to figure this out,” says Wilson, “and the last thing I need is BalloonBoy1817 being like, Ohhhhh. I hate this!”

So they went to great lengths to hide, going so far as to eat out at a “Dining in the Dark” establishment—servers wear night-vision goggles—though they did reveal what was becoming an open secret to some friends. A few years back, Adebayo and Wilson attended a birthday gathering for Miami player Udonis Haslem. Heat Hall of Famer Dwyane Wade was in attendance, along with his wife Union. “We stared and cheesed so hard at her,” says Union. “When she finally looked up, she was faced with a wall of supportive grinning fools. While probably a lil’ creepy, hopefully she felt the love.”

She did. And it was. “It’s like, ‘Can you pass the bread?’” says Wilson. “‘Can we just be normal?’”

When they shared a secret handshake at the Paris Olympics, the gesture offered internet gossips more evidence of a romance than, say, a big ol’ kiss. Now they show up beaming with pride for each other’s key moments. Adebayo sat courtside when South Carolina retired Wilson’s jersey in February, presented her with her fourth MVP trophy in September, and shared an emotional embrace with her on the court after she clinched the title.

The 6-ft., 9-in. big man serves as her defensive foil in workouts, forcing Wilson to take more difficult shots than she ever would against smaller WNBA competition. (She’d practiced, for example, that Game 3 fadeaway many times with Adebayo.) He sometimes takes things a bit too far. She’ll pump fake, and he’ll jump by her. But his quickness and height allow him to recover and still contest her shot from behind. “I’m just like, ‘No one in our league can do that,’” says Wilson. “Well, me, maybe. I get mad at times because I’m just like, ‘OK, now be a WNBA player. Don’t do that.’”

“She failed to mention,” says Adebayo, “that I’ll block that sh-t into the second row.”

They team up for shooting drills: one player has to hit a certain number in a row before they can stop. If Wilson’s hot, she’ll tell him her back hurts, from carrying them. That fires Adebayo up; he’ll then bang 10 in a row. “We make each other better,” says Wilson. “We sharpen each other’s skills. That’s kind of what makes us go. The gym is a happy place.”

Some five hours before the start of the Aces championship parade, fans line up near T-Mobile Arena plaza. Bernice Malcom, 92, a sharecropper’s daughter who grew up in North Carolina, never imagined a scene like this. A women’s basketball team led by a Black woman from the South that sells out the professional sports arena she’s looking up at. “Oh, I’m crying now,” says Malcom. “A’ja’s not the only one who can do that. Other little girls can do that. It’s very heartwarming. They don’t have to go and work hard like I did in the cotton fields.” Consandra Amerson, a retired probation officer, is there with her 7-year-old granddaughter, Ariah Banks, who has a Wilson shrine in her home: a Funko Pop figurine, basketball cards, blankets, books. Amerson owns a trio of Wilson jerseys and 14 pairs of A’One signature shoes, which Nike released, at long last, this spring.

Wilson was the first Black WNBA player with a new shoe since 2011, when Adidas put out a Candace Parker model. Nike hadn’t released a shoe for a Black women’s basketball player in more than two decades. “We, as Black women, get shaken,” Wilson says. “We get swept underneath the rug. Was it overdue? Absolutely.”

Supporters would ask Wilson why she didn’t have her own shoe, and she couldn’t give them an answer. Now she’s motivated to make sure such a gap never happens again. “When I have these seats at the table,” says Wilson, “I’m clearing space for people to bring their chairs up too.”

Nike’s A’One commercial features young Black girls playing a clapping game, dancers from Benedict College, an HBCU in Wilson’s hometown, and scenes from a Black church, all celebrating Wilson’s roots and Black Southern culture. “Nike kind of lost its funk,” says Wilson. “We kind of fell into this, like, cookie-cutter ‘We’re just gonna push shoes. We’re just going to do this and get out of the way.’ No.”

When asked whether she agreed, Karie Conner, the company’s vice president and general manager of global basketball, said, “We want our athletes to push us every time that we come together and co-create our product. So I appreciate her pushing us.” On its May 6 release date, the A’One Pink Aura sold out on nike.com in three minutes. Nike says the shoe also sold out in stores in the greater China and Europe, Middle East, and Africa regions.

This performance spoke volumes about the WNBA’s marketing potential, even in the face of adversity. As a majority-Black, socially progressive league with a strong LGBTQ+ presence, it has always been a troll target. This season, some right-wing influencers cheered fans who threw sex toys on the court at games. Donald Trump Jr. made light of these incidents, posting a doctored image of his father throwing one from the roof of the White House. Picking on the league has won political points before. “MAGA Is Coming for the WNBA,”screamed a September headline on Politico.

Wilson seems unfazed. “We’ve been told to make sandwiches and get in the kitchen for the longest,” she says. “If we can get through bullying of those types, I don’t think bullying is going to ever shake us.”

More front of mind for Wilson and her colleagues is money. In September, Minnesota Lynx star Napheesa Collier made seismic waves when she called out WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert for comments she allegedly made to Collier in February, including that Clark “wouldn’t make anything without the WNBA platform” and that players “should be on their knees thanking their lucky stars” for the media-rights deal she secured. At a press conference, Engelbert denied making the comment about Clark; when asked about the “lucky stars” remark, she responded: “There’s a lot of inaccuracy out there through social media and all this reporting … and I will tell you I highly respect the players.”

“I only know Cathy by when she hands me trophies,” says Wilson. “If that’s her true self, thank you for showing that. Thank you for saying those things. Because now we see you for who you are, and now we’re about to work even harder at this negotiation.” (A league spokesperson declined to comment further.) With franchise values soaring, media-rights deals richer, and viewership increasing—the WNBA is expanding to Portland, Ore., Toronto, Cleveland, Detroit, and Philadelphia in upcoming years—the players are seeking a bigger portion of a growing revenue pie. “We’re in a league where they’re like, ‘Oh, be happy you got private planes,’” says Wilson, who made $200,000 in salary this season. (The NBA MVP, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, signed a $285 million contract extension this summer.) “No. That was just scratching the surface.”

Lockout or not, Wilson plans on prepping hard for 2026. She wants to improve her ball handling, so she can initiate the Aces offense more often and dribble more freely on the fast break. “Just another weapon and an element that I can add to my game that puts the defenders on their heels,” says Wilson. Hammon endorses this approach: she says the Aces score an extra point per possession when Wilson brings the ball up the floor.

I ask Wilson how many more championships she has in her. “I think I can do three more,” she says. Jordan, perhaps not coincidentally, also won six. After Vegas won the title, she was asked about the comparison to Jordan and seemed surprised. Now she has warmed to it. Air Jordans. A’Ones. North Carolina. South Carolina. The two striking photos of Finals excellence. They both stick their tongues out when performing on the court. Sure, Wilson is probably a friendlier teammate. But locker-room decorum aside, it’s not far-fetched. “That right there is everything I want,” says Wilson, about joining the Jordan conversation. “Give me rings. Let me take the picture and really show off who I am. I don’t want to have to be somebody that’s like, ‘Yep, I’m A’ja Wilson, everybody.’ I could also hold this aura and impact where everyone’s like, ‘Oh no, that’s A’ja Wilson.’ And I don’t have to say a word.”

Set Design by Gabriela Soto; Styling by Rául Guerrero; Hair by Harold Harper; Make-up by Nathalie Pierre; Production by Rob Uguccioni

The post A’ja Wilson Is TIME’s 2025 Athlete of the Year appeared first on TIME.