How do we reckon with the legacy of people who have done excellent work, but who have said or done terrible things?

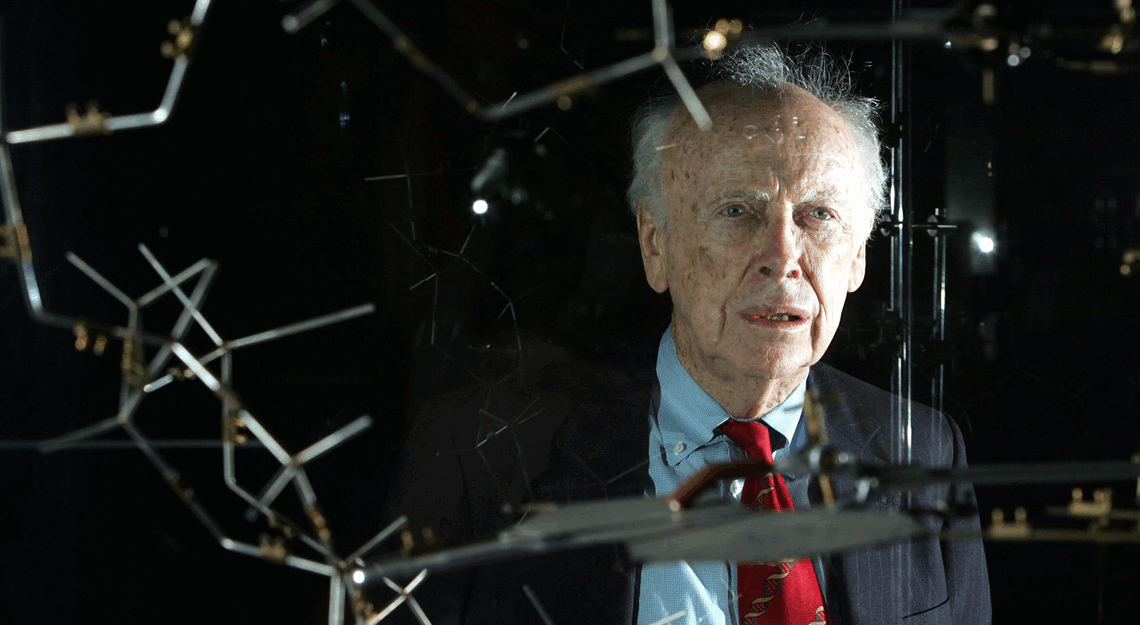

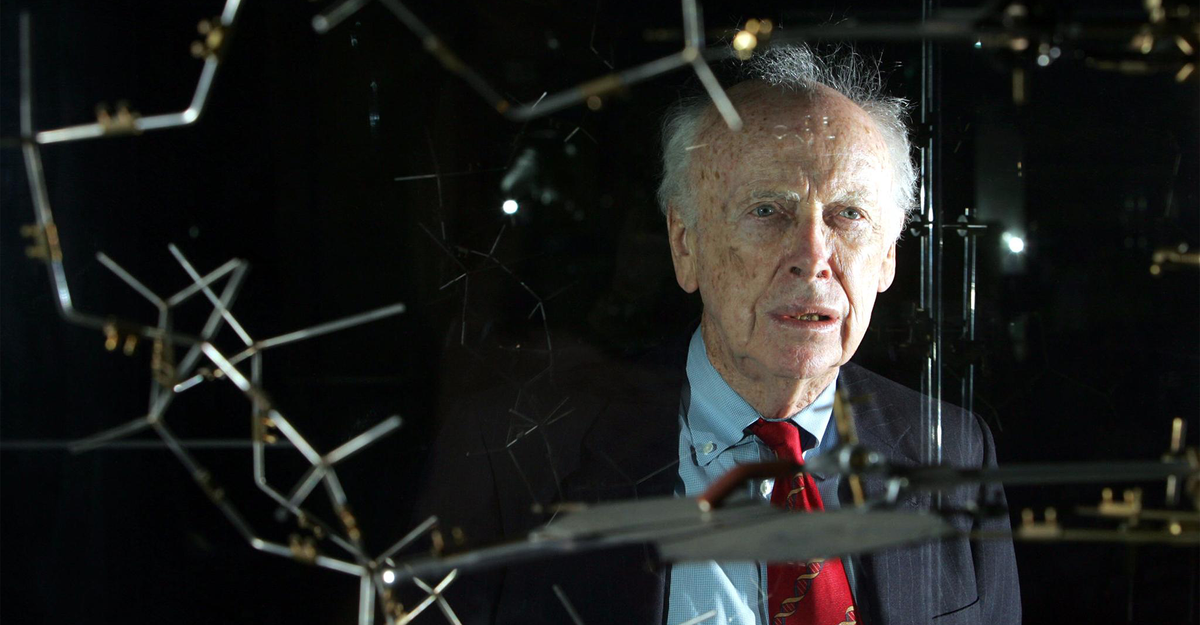

Last week, James Watson died at the age of 97. Watson’s scientific work was certainly excellent. He was chiefly known for publishing, with Francis Crick, the first description of the structure of DNA, a discovery for which they received a Nobel Prize in 1962 and which he described in his best-selling memoir, The Double Helix. In addition to his reputation for scientific innovation and leadership, however, Watson was notorious for his bigotry. For years, he made derisive comments about gay people, suggested that women were less effective scientists, and claimed that people of African descent were biologically inferior, and in particular, that they had lower inborn intelligence.

The root of reckon is “count,” and to ask what to make of a life like Watson’s risks suggesting that the triumphs and sins of a human life can be quantified on the same numerical scale. How many racist comments must be subtracted from a Nature paper before the total is negative? Of course, human lives defy this type of mathematical flattening. We can add three and two to make five, but we cannot add scientific breakthroughs to bigotry and arrive at a tidy, incontrovertible sum. One deed sits stubbornly beside the other.

This complexity is particularly maddening in a scientist like Watson. He was a transformative leader in his field: He revitalized the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory into a scientific powerhouse, and he was instrumental in the initiation of the Human Genome Project. He also regularly acted with, as Cornelia Dean wrote in his New York Times obituary, “brash, unpleasant and even bigoted outspokenness,” making pseudoscientific assertions that led to his becoming, as Stat News put it, a “pariah” among his peers, forced into early retirement and stripped of honorary titles. Instead of seeing in our DNA evidence of how deeply interconnected we are—all part of the same family tree, all part of the same tree of life—Watson saw, or thought he saw, evidence only of fundamental difference.

As psychologists who study how genes influence human behavior—and, just as crucially, the limits of that influence—we cannot help but wonder how these strands of his intellect and character came to co-exist. Part of the problem might have been how a certain sort of scientific thinking can be fetishized. There’s a danger in slipping between different conceptions of “reason.” The analytic problem-solving skills that are selected for and honed in a scientific career are not synonymous with sound moral reasoning. Watson made his biggest scientific discovery as a young man, only 25 years old, and his sense of his own abilities, his own specialness, seemed never to mature beyond a young man’s bravado. It’s morally perilous to assume that you are always the smartest person in the room, and that the specific ways in which you are smart are always the surest paths to wisdom.

Neither did Watson update, as genetics matured as a science, his sense of the limits of molecular analysis. As Watson and Crick noted in their original publication, the double-helix structure of DNA implicated a straightforward mechanism for how the genome changed and replicated, and that insight transformed biology into a mechanistic science. But understanding how DNA mutates and replicates has not similarly transformed psychology; the study of the mind has not been reduced to the study of molecules. Despite astonishing progress in molecular genetics since Watson and Crick’s discovery, we are scarcely closer to understanding the genetics of human intelligence than we were in the 1950s, and are perhaps even further away from a consensus definition of what sort of thing “intelligence” even is. Watson made an error that has dogged human genetics from the beginning: He assumed that the discovery that we, too, are DNA-based creatures meant that sometime soon, all differences among people would be explained by biological mechanisms. Again and again, that assumption has turned out to be not only wrong but profoundly dangerous. In the 20th century, it justified eugenic violence; in the 21st, it has continued to justify racial inequality.

[Read: The far right is becoming obsessed with race and IQ]

Watson’s life story also has been warped by the myth of the lone genius, or in the case of Watson and Crick, the lone geniuses. Watson and Crick’s discovery of the double-helix structure was built on the work of Rosalind Franklin, who produced an X-ray image of the DNA molecule; of Friedrich Miescher, who first isolated what he called “nuclein”; and of Gregor Mendel, whose experiments with pea plants first revealed statistical laws of inheritance, to name just a few colleagues and forebears. Watson’s work in Cambridge was also supported by a fellowship from what is now called the March of Dimes, established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to fund scientific research into the treatment or eradication of polio. As with any scientific achievement, Watson could not have made his alone.

Watson and Crick’s 1953 paper, with its neat hand drawing of the double helix, is still a thrilling read: What it must have been like to apprehend this structure for the first time! The discovery represents the peak of a cresting wave of scientific invention, industry, and investment. Watson deserves credit for how well he rode that wave, but not for the deeper forces that made his work, in that moment, possible. The discovery was a collective human achievement, the result of the sustained cooperation of many people, over many years.

To reckon with Watson’s legacy, then, we propose celebrating what he wouldn’t—or couldn’t—recognize: the shared intelligence of the human race, which can produce miracles and wonders, even as each of us, individually, is so terribly fallible.

The post The Paradox of James Watson appeared first on The Atlantic.