In March 1938, paramilitary groups in leather boots and brown uniforms marched through the streets of Vienna. Part of ‘s Sturmabteilung (SA), they were celebrating Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria. As two SA members hung a sign that read “I am a Jewish pig” around an old woman’s neck, a man pushed through the crowd to help her. A fistfight ensued but the man was lucky to have survived. Resisting the was dangerous then, and he landed in prison.

But he didn’t stay long behind bars because of his name. After all, Albert Göring was the brother of Hermann Göring, Supreme Commander of the Air Force and one of Hitler’s closest confidants. Yet, unlike his brother, Albert was actively involved in opposing the Nazis. “What he saw was against everything that he believed in and he had no option,” says William Hastings Burke, author of the book “Thirty Four: The Key to Göring’s Last Secret.”

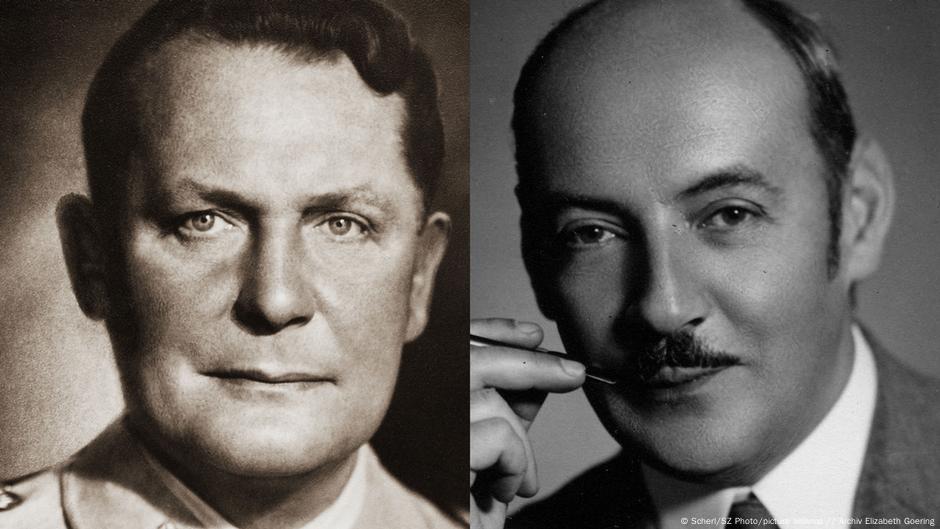

Brothers, but polar opposites

How could two brothers turn out to be so different? Hermann was power hungry and narcissistic, while Albert was a charming bon vivant opposed to the Nazis like . While Hermann was already Hitler’s supporter by 1922, Albert had no political ambitions of his own and rejected Nazi ideology and its brutality.

A mechanical engineer, Albert moved to Vienna in 1929 and and joined the film industry in the early 1930s as technical director at Tobis-Sascha Filmindustrie AG. He was concerned about the developments in Germany, where the Nazis were persecuting and dehumanizing Jews and political opponents. It might seem strange, says William Hastings Burke, but it was actually Hermann who asked his younger brother to help the actress Henny Porten get a role in a movie. Porten was a star of the silent film era who could no longer work in Germany as she refused to leave her Jewish husband. Henny was also a friend of Hermann’s wife Emma, and Albert was happy to help.

Helping Jews flee

Two years later, — the Nazi minister of propaganda — wanted to integrate the Tobis-Sascha film production company into his propaganda machine. Albert’s former boss, Oskar Pilzer, had been one of the most successful film producers in Europe before an employment ban for Jews was enforced by the Nazis. When the Gestapo came to arrest him, Albert intervened and personally accompanied Pilzer to the Italian border.

This was not the only time that Albert helped others escape. While his brother worked on expanding the German Air Force, Albert forged documents, organized escape routes and provided money to those who had to flee. His surname was often intimidating to many Nazi officials. He’d also intervened on behalf of composer Franz Lehár, whose wife Sophie was Jewish. He asked Hermann to register the Lehárs marriage as a “privileged mixed marriage,” thus saving Sophie from deportation to a concentration camp.

Hermann Göring’s priorities

Albert Göring often enlisted the help of his powerful older brother for these rescue operations, which surprisingly, Hermann Göring obliged. Despite his ruthlessness as a politician, he was lenient when it came to his family, says Burke. “Actually, Albert was a huge headache for Hermann. But I guess Hermann had no option because that was his brother, he loved him and couldn’t just sacrifice him.”

Burke adds that Hermann had a clear hierarchy: He came first, followed by his family, the fatherland, Nazism and Hitler. “He was like the godfather of the family. That’s him pandering to his own ego, but also him acting on behalf of his family, helping his brother,” Burke explains.

In 1939, Albert was appointed export director at the Skoda Works in Brno in what was then Czechoslovakia, which was under Nazi occupation. “A lot of people said that Albert began to work at Skoda because his brother had the power and gave him the job,” explains Burke. However he thinks it was probably the opposite, with the Czechs believing this could help protect their interests by having “someone who has a direct line to the big boss in Berlin.”

Under Gestapo surveillance

Albert fulfilled those expectations. He stood up for the Czechs and actively supported the Czech resistance by passing on secret information, like the precise location of a submarine dockyard or plans to break the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. He had access to this information by merit of his business contacts and through his brother.

According to eyewitness reports, Albert continued to help others escape the Nazi regime. He is said to have picked up Jewish prisoners from the to do “war-essential” work at Skoda Works. Jacques Benbassat, one of the few surviving witnesses who had known Albert Göring intimately and extensively, recalled to Burke that, “the warden at the concentration camp agreed to this because the request came from Albert Göring. The trucks would stop in a forest, and their passengers were then allowed to escape.”

But Albert’s actions became increasingly reckless, and he was long in the Gestapo’s sights and was eventually declared an enemy of the state. Yet, even then, he wasn’t imprisoned due to his brother Hermann’s protection. William Hastings Burke explains: “In October 1944, when Herman Göring’s power in the Third Reich was at an all-time low, he still stepped in and risked his political neck to help save and intervene on Albert’s behalf.”

The curse of the Göring name

The brothers’ loyalties remained unchanged. After the collapse of the Third Reich, both men were imprisoned. During interrogations, Albert refused to speak ill of Hermann and praised what he described as his “warm-heartedness.” The Americans didn’t believe that Albert hadn’t been a Nazi himself. “So the same name that enabled him to save people ended up contributing to his own downfall. It was a curse,” explains William Hastings Burke.

On September 19, 1945, US investigator Paul Kubala wrote: “The results of the interrogation of Albert Göring … constitutes as clever a piece of rationalization and ‘whitewash’ as the SAIC (Seventh Army Interrogation Center) has ever seen. Albert’s lack of subtlety is matched only by the bulk of his obese brother.”

The “Thirty Four” of Burke’s book title actually refers to the 34 names that Albert Göring had listed in alphabetical order, which he described as, “People whose lives I saved at my own risk (three Gestapo arrest warrants!).” No one ever tried to look for the people on Albert’s list — although it also included high-profile names.

Things however changed for Albert once a new interrogation officer took over his case: Victor Parker was the nephew of Sophie Léhar, who was also on Albert’s list. While Hermann Göring committed suicide the night before his scheduled execution, Albert Göring was released. But “he was a pariah in his own country because of his name,” says Burke.

After the war, Albert couldn’t find any employment as an engineer and survived on doing odd jobs and translations. A social outcast, he was shunned until his death in 1966, at the age of 71.

Albert Göring as a role model — even today

“It’s such a sad story,” says William Hastings Burke, who has been obsessed with this story ever since he heard about it for the first time in a TV report. Burke travelled to Europe and searched for material on Albert Göring, sifting through archives and meeting former associates or relatives of people whom Albert had helped. He even tracked down his grave.

“I thought, I need to tell the world about this man,” recounts Burke. His book may have been published in 2015 but Albert Göring remains on his mind. To him, Albert is a role model: “Albert was a man who stood up to this regime. But after the war, he didn’t go and tell the world about it. He wasn’t interested in fame; he simply preserved his humanity.”

Burke however adds that while 1930s Germany cannot be compared with the world today, “I think that’s a very powerful example that’s really important for today.”

In fact, Burke has submitted a request to the Yad Vashem memorial for Albert Göring to be listed as “Righteous Among the Nations.” He hopes that one day it will be granted.

This article was originally written in German.

The post Hermann und Albert Göring: Two very different brothers appeared first on Deutsche Welle.