On a Mexican island in the Pacific Ocean, a reptile with seafaring ancestors has been vindicated.

The spiny-tailed iguana has long been assumed to be invasive on Clarion Island. But now, biologists say the lizard actually landed there nearly half a million years ago, long before any humans might have transported them from the mainland. Researchers reported the discovery last month in the journal Ecology and Evolution, and the finding means that the animals should be able to continue living on Clarion Island.

Clarion Island is the westernmost of the Revillagigedo Islands, a remote, mostly uninhabited Mexican archipelago in the Pacific Ocean. There are around 100 iguanas there, and scientists and locals alike assumed that they had arrived in the late 20th century, introduced by humans because they had gone unmentioned in prior accounts of the island’s fauna.

“It was all speculative that they were introduced — no one ever tested it,” said Daniel Mulcahy, an evolutionary biologist at the Museum of Natural History in Berlin who is an author of the new study.

In 2013, Dr. Mulcahy, then at the Smithsonian Institution, visited Clarion to study a rumored snake species. While there, he spotted iguanas and collected some DNA specimens. He noticed the genetic material didn’t quite match that of the spiny-tailed iguanas on the mainland.

A decade later, a colleague called him to say he thought the Clarion iguanas looked different from those on the mainland and were possibly native to the island. The government was planning to exterminate them, thinking they were invasive and harming the island’s delicate ecosystem.

“He was like, ‘We’ve got to tell them don’t do that,’” Dr. Mulcahy said. He decided then to publish his DNA analysis.

To vindicate the accused iguanas, Dr. Mulcahy and his colleagues compared mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down maternally, from the Clarion iguanas and the mainland spiny-tailed iguanas. There was around a 1.5 percent difference in their DNA — meaning the island iguanas are genetically distinct and couldn’t be recent invaders from the mainland, Dr. Mulcahy said. Instead, they diverged genetically from spiny-tailed iguanas found in northwestern Mexico.

The team then used genetic data and fossils from more distantly related species to see when the Clarion iguanas had split off from the mainland animals.

They probably diverged around 425,600 years ago, hundreds of thousands of years before humans arrived in the Americas. Their presence on Clarion suggests a roughly 700-mile rafting trip on a floating mat of vegetation by an intrepid group of animals. It would be the second-longest known aquatic journey taken by iguanas, topped by another species of iguanas that traveled nearly 5,000 miles from North America to Fiji.

The study “comes in the nick of time,” said Greg Lewbart, a wildlife veterinarian and herpetology expert at North Carolina State University who was not involved with the work. “What could be worse,” he asked, than eradicating a native animal from the island?

Some wonder how a four-foot-long, black-and-yellow lizard went unnoticed on Clarion Island for decades. One possibility is that the island’s landscape has changed dramatically in recent years, Dr. Mulcahy said. Once covered in prickly pear cactus that made exploration difficult, its native flora was consumed by sheep and pigs introduced in the 1970s by the Mexican Navy. Now, those animals are gone and mostly chaparral remains.

The iguanas are also wary of humans and hide when approached.

The destruction caused by the sheep and pigs underscores how damaging invasive animals and human disturbance can be. Island ecosystems are particularly vulnerable, said Rayna Bell, an evolutionary biologist at the California Academy of Sciences.

“This type of work is fundamental to conserving some of the world’s most unique and imperiled diversity,” added Dr. Bell, who was not involved with the study.

Dr. Mulcahy’s colleagues are working to spread the news to government officials in Mexico, aiming to ensure that Clarion Island iguana eradication programs are stopped.

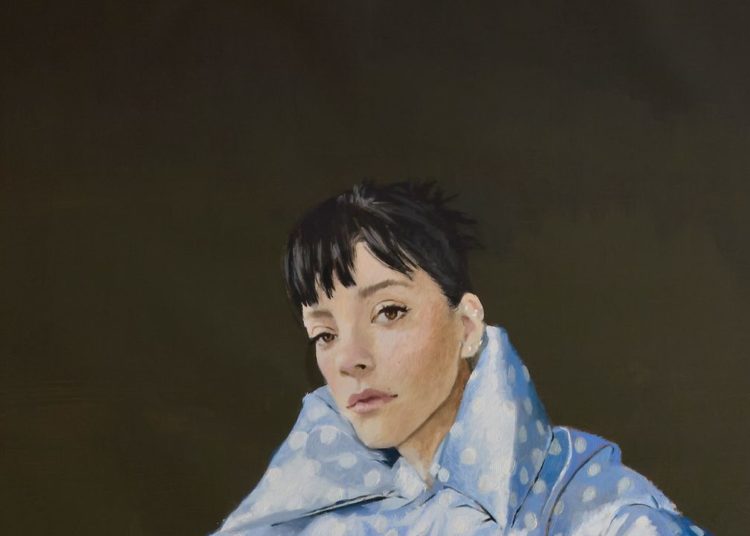

The post This Is What a Vindicated Iguana Looks Like appeared first on New York Times.