The director Richard Linklater is cinema’s reigning king of the chill hang, capable of mining compelling drama from the most blissed-out characters. So I was initially thrown by his choice of subjects for his two latest films, released back-to-back: a pair of real-life visionaries uninterested in following artistic conventions. But taken together, the movies demonstrate Linklater’s interest in probing creative temperaments, including his own. Like his protagonists, the filmmaker went against the grain at the start of his career. Now, in his late-middle age, a much more flexible Linklater is ruminating on other notorious artists.

The first of the films is Blue Moon, a sweet-and-sour portrait of the lyricist Lorenz Hart (played by Ethan Hawke) melting down at a bar near the tail end of his Broadway career. The second is Nouvelle Vague, which giddily depicts the making of the French New Wave classic Breathless; by the end, the entire cast and crew have been driven up the wall by their mercurial director, Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck). The two movies are wonderfully complementary, even if their close release dates are seemingly a coincidence. In both cases, Linklater is reckoning with what it’s like to be a creative person on the fringe. In Blue Moon, Hart has been kicked from atop his perch of success, and in Nouvelle Vague, Godard is a former peanut gallerist now trying to break into the industry without following any of the rules. Neither character fits in with Linklater’s roster of laid-back protagonists, established with movies such as Dazed and Confused. Yet the two films represent how deep the director’s bench has become in the decades since then.

Linklater’s career has shape-shifted many times over the past 35 years. He arrived on the nascent indie scene with the micro-budget movie Slacker in 1990, a meandering film that helped define a decade of free-spirited art-house cinema. He’s worked on experimental animation, crime thrillers, and studio comedies, some of which hit (School of Rock) and some of which didn’t (Where’d You Go, Bernadette); he turned the romance Before Sunrise into a trilogy of Gen X classics; he spent more than a decade making the drama Boyhood, for which he received several Oscar nods. And last year saw the release of Netflix’s Hit Man, a fizzy black comedy that picked at the squeaky-clean star image of its lead actor, Glen Powell.

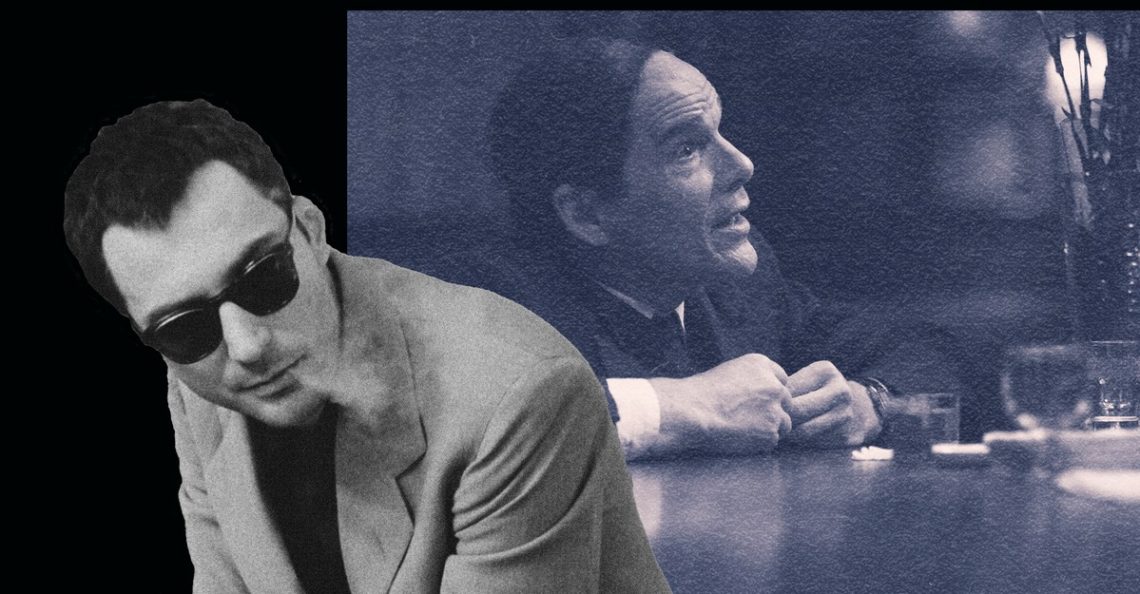

Nouvelle Vague, also on Netflix, is about another flashy charmer, Godard, whose dark sunglasses and ever-lit cigarette belied some truly revolutionary ideas about art. Netflix is an ironic home for a swoony love letter to cinema; the streamer remains fairly uninterested in the theatrical experience. When Godard made Breathless, in 1960, he too served as a disruptor of sorts. Godard was a cinephile and a vital film critic who, along with his contemporaries (François Truffaut, Agnès Varda, and Claude Chabrol), sought to reinvigorate French moviemaking. He became known for blending pulpy American storytelling with effortless European cool. Although Linklater is a more affable fellow than his subject, his early films were also disruptive: low-budget productions made way off the Hollywood grid, which nevertheless got mainstream attention.

Nouvelle Vague is a fairly straightforward making-of story—funny, considering how form-breaking Breathless was. But Linklater understands that his movie’s appeal lies in character-based humor. He portrays Godard as an untested, off-putting oddity to those around him: Handed a crime story by Truffaut and some money by skeptical industry types, Godard launches the production as a piecemeal operation. He gives the actors their lines minutes before shooting. Sometimes he goes days without filming much at all.

The shoot is bizarre, especially for the picture’s Hollywood star, Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch). But other members of the cast and crew, such as her co-star Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) and the cinematographer, Raoul Coutard (Matthieu Penchinat), perceive some real vision behind the chaos, even if they can’t figure out how it’ll all work. Linklater is thematically drawn to partnership and camaraderie, and he manages to wring remarkable sincerity out of even the silliest premises. Here, the director wrests a radioactive joy from observing Godard generate ideas with his ensemble, even as others pull their hair out around him.

Blue Moon is the other side of the idiosyncratic-artist coin, examining not the airy start of something major but a man bereft of his best collaborator. Hart was, for decades, the other half of a duo with Richard Rodgers; they added hundreds of standards to the Great American Songbook and co-wrote musicals such as Pal Joey and A Connecticut Yankee. Blue Moon finds Hart after their breakup, on the opening night of Oklahoma—Rodgers’s first collaboration with the man who would become his best-known partner, Oscar Hammerstein II. The film is set entirely at Sardi’s, the legendary Broadway haunt, where the drunken and depressive Hart is holding court at the bar. He locks other patrons into conversation as he waits for a triumphant Rodgers (Andrew Scott) to walk in.

Blue Moon sees Hart confront his lack of a professional future, nearly in real time. Despite the wistful tone, it’s a bitingly funny viewing experience. Shrunken to Hart’s height and given his balding pate, Hawke is transfixing in the role; as Hart, he holds everyone’s attention whenever he’s monologuing. The character’s rapt audience, however, looks at him with a mix of pity and regret. A Sardi’s bartender, Eddie (Bobby Cannavale), puts up with him best, allowing the floundering lyricist to loudly critique Oklahoma and boast about imagined sexual conquests. The cordial New Yorker writer E. B. White (Patrick Kennedy) shows up to trade anecdotes with Hart, fascinated by his sharp decline. Later, of course, Rodgers appears, treating his old partner with steely politeness.

Linklater could have made Nouvelle Vague at any point in his career. The film is an exegesis on the strange magic of filmmaking: Sometimes, against all odds, things just come together. But Blue Moon seems like a newer area of focus for the director. The small-scale tragedy depicts an undeniable artistic force who simply could not get out of his own way. (One wonders if Linklater is pondering the darker directions his career could have gone.) The two movies are fascinating to watch in tandem as a meditation on the unpredictability of making it in the arts—including Linklater’s own path, which has taken him on a strange, winding journey in and out of the mainstream. No matter the talent involved, he seems to argue, creative success is a crapshoot.

The post Two Unlikely Biopics About Unlikable People appeared first on The Atlantic.