The Trump administration is wielding the possibility that parts of the economy are in a recession as it raises pressure on the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates, hoping to ensure that the central bank will bear the blame for any economic weakness.

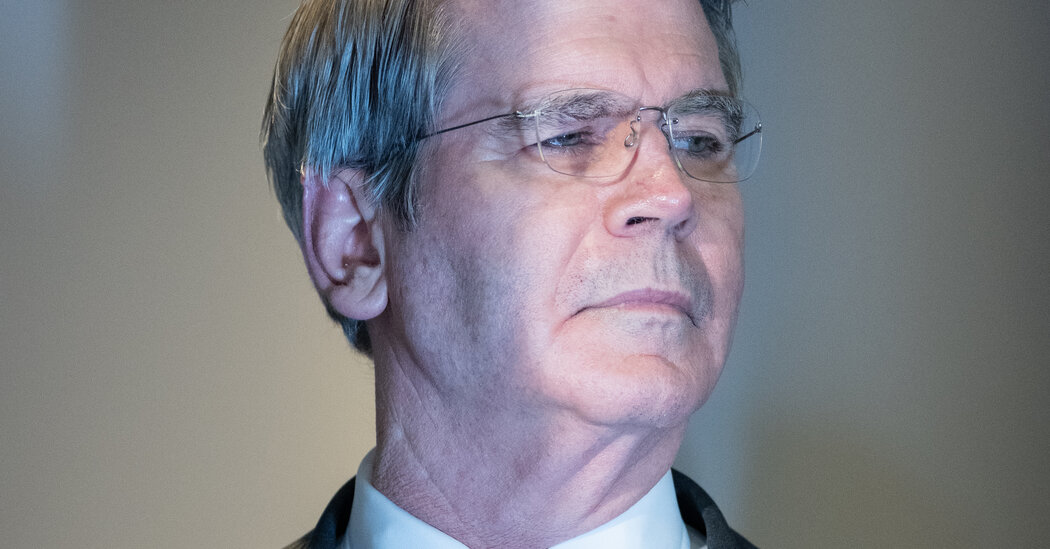

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Stephen Miran, President Trump’s appointee to the Fed’s Board of Governors who is on a temporary leave from his job leading the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, this week struck a downbeat tone about the health of the world’s largest economy. Mr. Bessent went so far as to say some sectors were already contracting. He did not specify which sectors, but high mortgage rates have put housing and adjacent industries such as construction under pressure.

“I think that there are sectors of the economy that are in recession,” Mr. Bessent said on CNN on Sunday. He described the economy as being in a “period of transition” because of a pullback in government spending to reduce the deficit. He called on the Fed to support the economy by cutting interest rates.

Mr. Bessent’s remarks added to pressure on the Fed and deflected blame from Mr. Trump in case the economy does ultimately face a downturn, reinforcing a strategy that has been in place since the start of the year. As the administration has imposed aggressive tariffs on nearly all of America’s trading partners and slashed federal spending, potentially slowing growth, it has sought to pin blame squarely on the Fed in the event of an economic downturn.

“This is all going to be put at the Fed’s feet,” said Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist for the accounting firm RSM.

For months, Mr. Trump has assailed Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, for moving too slowly to lower interest rates. That has included branding Mr. Powell as “Mr. Too Late” and a “numbskull.” Over the summer, he escalated his pressure campaign on the central bank and took more aggressive steps to reshape the top ranks responsible for making policy decisions.

Mr. Trump is in a legal battle set to be decided by the Supreme Court after his attempt to oust Lisa Cook, a governor, from her position over allegations of mortgage fraud. In August he appointed Mr. Miran, who at the time was one of his top economic advisers, to the Fed’s Board of Governors after one member, Adriana Kugler, stepped down before her term ended.

Since joining the central bank in September, Mr. Miran has pushed hard for substantially lowering interest rates. In an interview with The New York Times on Friday, he warned that the Fed risked causing an economic downturn if it did not do so.

“If you keep policy this tight for a long period of time, then you run the risk that monetary policy itself is inducing a recession,” he said. “I don’t see a reason to run that risk if I’m not concerned about inflation on the upside.”

But that view is not widely shared by other Fed officials or by most economists across Wall Street. At the past two policy meetings, Mr. Miran has been the lone dissenter in favor of a bigger, half-point cut. Last month, most policymakers backed a quarter-point reduction, while one official dissented in support of keeping interest rates steady because of his concerns about inflation.

Mr. Bessent’s mention of a recession is unusual for a Treasury secretary; downturns can become self-fulfilling if consumers and businesses pull back in anticipation of a contraction.

Despite Mr. Bessent’s comments, the Treasury Department said this week in its statement on the economy for the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee that it did not expect a recession.

“Looking ahead to the next few quarters, the outlook for the U.S. economy faces upside and downside risks,” Treasury economists wrote. “However, on balance, economists view the risk of a recession as relatively low.”

They noted that the federal government shutdown and declining federal employment were headwinds for growth. The labor market had been flashing some worrying signals in recent months before the shutdown caused, in effect, a blackout of government statistics. Job growth had ground to a halt, and the breadth of sectors actually hiring had narrowed.

Those trends appear to have continued. And yet, Mr. Powell and other officials like John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, have not conveyed much concern about the economy’s tipping into a recession.

Mr. Powell, at a news conference after the Fed’s latest meeting to set rates, questioned whether there would be sufficient support to lower interest rates in December at a time when the Fed’s goals of low, stable inflation and a healthy labor market are in tension with each other.

As Mr. Bessent and Mr. Miran have asserted, the housing market does remain under significant pressure, a trend that began in 2023. But the Fed’s ability to lower interest rates, which would help support the housing market through lower mortgage rates, is significantly constrained because of the price pressures resulting from Mr. Trump’s tariffs.

Matthew Martin, a senior U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, said he did not view a recession as the most likely outcome for the economy, though he conceded that the Fed was walking a “tight path” and that some cracks had emerged in the economy’s foundation.

Some industries have felt more pain than others amid uncertainty over tariffs and other Trump administration policies. Perhaps the most noticeable, Mr. Martin said, was the pullback in the manufacturing sector despite the administration’s efforts to revive it.

“That’s an area where tariffs increased uncertainty and decreased demand,” he said.

Factory activity contracted for an eighth straight month in October, according to survey results released Monday by the Institute for Supply Management. Manufacturers have also continued to shed workers.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, said that while the national economy was not in a recession, it appeared to be struggling to avoid one. In an analysis last month, he found that 22 U.S. states plus the District of Columbia were in or near a recession and that the fate of the economy could hinge on how California and New York fare in the coming months.

“Only a few industries are still adding to payrolls, mainly health care and hospitality,” Mr. Zandi said. “Construction, manufacturing, technology, finance, government and many professional services are shedding jobs.”

Alan Rappeport is an economic policy reporter for The Times, based in Washington. He covers the Treasury Department and writes about taxes, trade and fiscal matters.

Colby Smith covers the Federal Reserve and the U.S. economy for The Times.

The post Trump Aides Raise Recession Fears, and Point Fingers at the Fed appeared first on New York Times.