JERUSALEM — For decades, Hinda Koza-Culp’s family clung to a black-and-white photograph and a haunting story: Her great-grandmother’s six siblings and parents were all murdered in the Holocaust, their names largely lost to history.

Then last year, Koza-Culp typed her great-grandmother’s maiden name, Litvak, into an online database and discovered something she never could have imagined.

Two of her great-grandmother’s siblings had survived. One of those siblings had a son living in Israel — and he wanted to talk.

“We spent so many years apart, so many years not knowing each other,” Koza-Culp told NBC News. “To take that back, to get some of that joy and love back … the best revenge is living well, I guess, as they say.”

Koza-Culp’s discovery was made possible by the Names Database at Israel’s Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center. And now, the very database that helped Koza-Culp find her family has reached an important milestone: Yad Vashem has recovered the names of 5 million of the estimated 6 million Jews murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators.

“Each person has not only [a] name, but also a fate and a face,” Sima Velkovic, the leader of Yad Vashem’s family roots research team, told NBC News. “We want to know: Who were these people?”

Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered approximately 6 million Jews across Europe — about two-thirds of the continent’s Jewish population — through mass shootings, forced labor, starvation and extermination camps such as Auschwitz. Millions of others, including disabled people and political dissidents, were also killed under Adolf Hitler’s regime.

Yad Vashem’s organized effort to restore Jewish victims’ names began in the 1950s and has stretched across generations, powered by survivors, their descendents and researchers determined to ensure every victim is honored.

How they did it

Reaching this milestone was not easy.

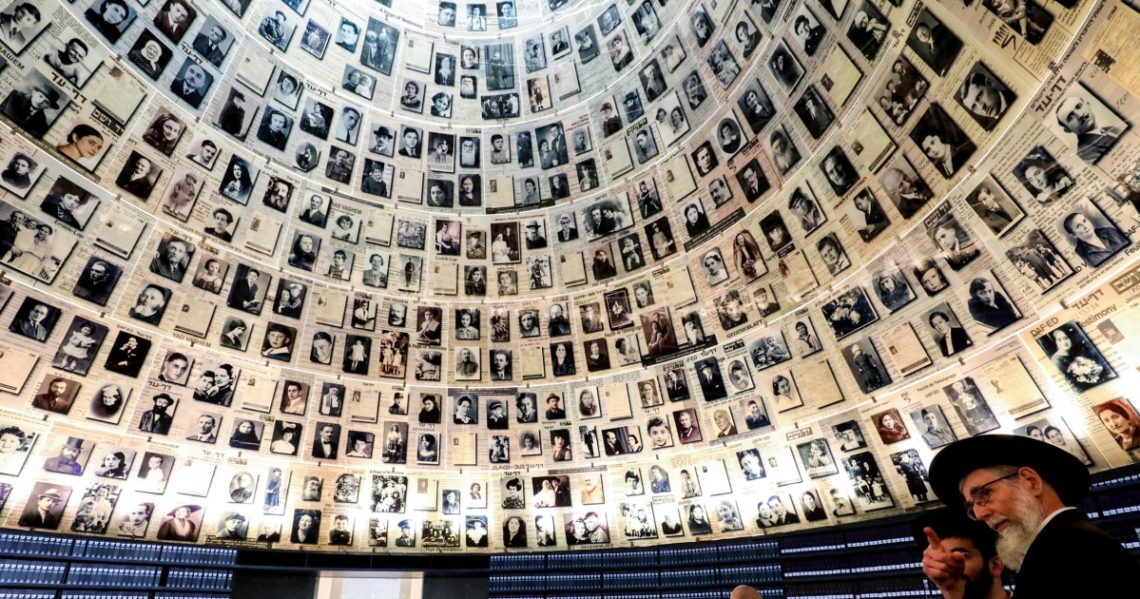

“There never was a list of Holocaust victims,” said Alexander Avram, director of the Hall of Names and the Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names at Yad Vashem.

“The Nazis and their collaborators did not issue death certificates. … In most cases the Jews were just killed or gassed or … no registration whatsoever,” Avram told NBC News in an interview inside the Hall of Names memorial.

Men, women and even children were shot into unmarked mass graves. At extermination camps, the Nazis burned the remains of Jewish victims in crematoria to hide evidence of genocide.

To reconstruct victims’ identities, Yad Vashem’s researchers have scoured tens of thousands of sources, including archival material.

One of the key sources has been “Pages of Testimony” — biographical fact sheets submitted by survivors and those who knew the victims to preserve their memory.

Each page is vetted carefully, Avram said. Researchers cross-reference submissions with prewar lists and historical events, sometimes requesting additional documentation before accepting a record.

The pages “can be considered tombstones for the Jews who were assassinated during the Holocaust,” Avram said.

For families like Koza-Culp’s, those pages are far more than data points. “To now be able to look at that photo and know their names … and to know a little bit about them, to me, makes them feel real and makes them feel like they mattered,” she said. “It makes them feel like they matter.”

Those names have also reunited branches of a family tree that had been separated for decades.

“The fabric of our family was ripped apart, and through this … we’ve stitched it back together a little bit, but … those scars are kind of always there,” she said.

The race against time

That sentiment drives Yad Vashem’s mission today, as historians race to preserve survivors’ memories while these eyewitnesses to genocide are still alive. Experts estimate that 90% of Holocaust survivors will have died by 2040.

New tools may help. Yad Vashem says artificial intelligence could help researchers scour archival material, possibly helping uncover around 250,000 more names.

But AI cannot track down names that are not in the historical record. Yad Vashem is imploring survivors and their descendants to share their stories now so that the very people Hitler hoped to erase are instead remembered for generations to come.

“This is the last hour,” warned Avram.

Jesse Kirsch reported from New York City, and Paul Goldman reported from Jerusalem.

The post Names of 5 million Holocaust victims identified, Israel’s Yad Vashem says appeared first on NBC News.