In early August, Clarence Toppo, a 38-year-old IT worker from the eastern Indian state of Bihar, learned from a friend that his mother was officially dead.

This came as a surprise to Toppo, for he lives with his mother, who is very much alive. Mary Toppo, 74, was only deceased in the eyes of the Indian government, which had recently launched a sprawling effort to verify the identity of every registered voter in Bihar—and to delete nonresidents and the deceased from the voter list. Clarence Toppo was vaguely aware of the verification campaign, he said, but nobody had contacted his family for documents, and they never got around to the paperwork.

Then Toppo received more surprising news: Toppo, who was born and raised in Bihar, apparently no longer lived in the state. Two of his brothers had also been marked as absent from the state—one had indeed moved away, but the other had not. “I am very shocked,” Toppo said from his house in Ara, a city in western Bihar. “If I live in India and my [voter] identification is taken and removed from me, that’s a very big deal.”

Toppo is both a Christian, a minority within Hindu-majority India, and a Dalit, historically the most marginalized group within India’s hierarchical caste system. Frustrated by what he saw as both a state and national government that ignored minority rights, Toppo had hoped to cast a vote for change in the state elections scheduled for November.

But after hearing that his family had disappeared from the voting list, he feared the chance was gone. Voting “gives us the reins to our country,” Toppo said. “It is our right to vote.”

Bihar’s voter verification process, which has provisionally disenfranchised millions, is the Indian government’s latest measure to tilt the electoral field in its favor in the world’s most populous democracy, civil activists and opposition political parties told Foreign Policy.

Roughly 6.8 million voters—8 percent of an electorate of about 79 million—were removed in total during Bihar’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR), as the process is called. The SIR is now awaiting a Supreme Court judgment on its legality, which could invalidate the new voter list.

During the first stage of the SIR, workers from the Election Commission of India (ECI) were given one month to visit each household in Bihar, request paperwork and documents for verification, and compile a draft voter list. “In one month, it is impossible to visit each and every house, each and every voter, ask them to submit their enumeration form, and attach” documents, said Sarfaraz Uddin, the Bihar general secretary of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), a national civil rights group.

The last SIR, held in 2003, took a year to complete. This time, overworked election officials, given vague instructions and each tasked with contacting nearly 900 voters in a month, turned to cutting corners. “When [workers] could not find anybody, they started submitting the form by themselves, by signing the documents with their [own] hand,” Uddin said. “Because of this arbitrariness, many genuine people were excluded and many people who are not present [in Bihar] have been included.”

But critics of the SIR fear the process goes beyond sloppiness. “If they selectively disenfranchise those who don’t vote for [the government], that will make a huge difference,” said Prashant Bhushan, a Delhi-based lawyer leading an effort to challenge the constitutionality of the SIR in the Supreme Court. “Normally, elections are won and lost by only 4, 5, 6 percent of votes.”

Bihar is the poorest state in India by GDP per capita, a result of repressive British colonial-era policies, subpar governance, and the loss of its mineral-rich regions, which became a separate state, Jharkhand, in 2000. Bihar is also a cauldron of unstable, caste-based politics—the same politician has led the state for more than a decade by repeatedly flip-flopping his allegiance between Bihar’s rival parliamentary blocs. Perhaps due to the state’s political turbulence, Bihar serves as the “test kitchen of Indian politics,” said Amir Abbas, the editor of the Bihar-based media organization Democratic Charkha.

In October 2020, Bihar was the first Indian state to press ahead with holding elections following the outbreak of the pandemic, prompting politicians to organize massive—and largely unmasked—rallies as COVID-19 raged throughout the country. Two years later, Bihar became the first state to collect data on caste in its census, a shift that the next nationwide census is also slated to include.

Abbas fears that the SIR is another experiment, one in political disenfranchisement. Critics allege that the process has been weaponized to systematically disenfranchise the voters—among them Muslims, Christians, and those belonging to the lower castes—least likely to support the ruling parliamentary coalition led by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The ECI originally specified that one of 11 possible documents could be accepted as proof of citizenship, but the Aadhaar card, a proof of residence card held by some 90 percent of the Bihari population, was not one of them. Instead, the documents that the SIR required—from 10th grade school enrollment forms to land deeds—were ones that a “very large percentage of the people” didn’t possess, said Bhushan, the lawyer.

On Sept. 8, the Supreme Court ruled that the SIR must also accept the Aadhaar as a form of verification.

During the second stage of the SIR, disenfranchised voters could challenge their removal from the voter list and re-register to vote. But in a state with a 70 percent literacy rate, many disenfranchised voters were unable to check the status of their registration themselves. The draft voter list was published on Aug. 1, but the list of excluded individuals was not published until more than two weeks later, on Aug. 17.

Much of the burden of informing people that they had lost the right to vote fell to opposition political parties and civil society activists. For weeks, Zaheeb Ajmal, a social activist in Patna, the capital of Bihar, went door to door in the city’s Muslim-majority Phulwari Sharif district to inform residents that their names had been struck off the voter list.

Ajmal said disenfranchised voters had told him, “‘We don’t know how to check [the voter list]. Our names have never been struck off. Why will our names be?’”

“There’s a lot of anger among people in the underprivileged section” of the city, he added.

Indecipherable addresses and wrong information on the deletion list only made the activists’ task harder. “The way the data has been presented, we can’t locate those people whose names have been deleted,” Ajmal said. “You can’t locate anyone until and unless you know someone in that” community.

Around 2.2 million people eventually registered to vote following the first stage of the SIR, though the majority of registrations were filed by new voters instead of disenfranchised voters, according to the ECI; at the same time, some 6.8 million people were struck off the voter list in Bihar.

The ECI may have also given workers politically charged instructions for whom to contact for verification and whom to exclude, Bhushan alleged. The ECI is “functioning as an agent of the BJP,” he said. “If they can selectively exclude people—say, minorities [or] Dalits—from the voter list and include the kind of people who do vote for the BJP, they’d like to do that.”

Toppo, the IT worker in Ara, suspects that his family’s dual minority identities played a role in the fact that no one from the ECI originally reached out to them. “I belong to a scheduled caste. I am a Christian. There is a possibility that my name has been cut from the voter list because of this,” Toppo said.

After a local journalist publicized Toppo’s story, an election official came to re-register the three members of his family, he said.

The consequences of the voter verification campaign will also extend far beyond just voting rights. In parallel with the Bihar SIR, the Modi government has launched an effort to forcefully deport—often on legally tenuous grounds—Muslims without identification documents under suspicion of living in India illegally. In Bihar, the ECI similarly claimed that the SIR would prevent foreign immigrants from voting illegally.

Opposition parties and civil activists fear that those who are removed from the voter list could eventually be targeted in the same way. “If their name does not remain on the voter list, tomorrow they will not remain as citizens,” said Kumar Parvez, a spokesperson for the opposition Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist).

Using voter registration as a proof of citizenship is a proven tactic under Modi’s BJP. Since 2019, the party has pledged to launch a nationwide campaign to confirm the citizenship status of all Indians. In the only state that has completed the citizenship verification to date, people could prove their ancestry by showing that a relative had appeared on voter lists issued before 1971.

Some Biharis now worry that the 2025 voter list could imperil their entire family’s citizenship in the future. “Future generations [of my children] will be asked, ‘Your grandfather was not a voter or a citizen. How did you come here?’” said Krishna Dayal Singh, a retired postal officer in Ara who was erroneously marked dead during the SIR.

After the draft voter list was released in the first stage of the SIR, an election official came to his house to re-register him as a voter, Singh said.

For others, voter registration is a literal lifeline. Jitni Devi, 92, used her monthly government pension of 1,100 rupees (about $12.53) to afford food and medication. During the SIR, only two out of the seven members of Devi’s household submitted their enumeration forms. Devi, who does not know how to read or write, initially did not take notice of the process, especially since election officials failed to visit her house in Alampur Gonpura, a village on the outskirts of Patna.

Yet when Devi went to claim her pension at the bank in August, she was surprised to learn that she was no longer registered in the system—and thus ineligible for her benefits. Later, a worker from Manthan, a local NGO, informed her that she had been marked dead during the SIR.

Devi is not particularly political—she would vote for whomever transported her to the voting booth, she said—but she now worries constantly about the loss of her benefits and how she will afford treatment for her high blood pressure and leg injury. “I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what the government is going to do to me,” she said. “I don’t know how I am supposed to live.”

It will be months before the full picture of the SIR’s consequences emerge. Though the final voter list was released on Sept. 30, the Supreme Court continued to hear arguments on the legality of the process through October and could invalidate the outcome of the SIR. Whether the BJP is set to continue to lead the ruling coalition in Bihar will be unclear until the conclusion of the state elections on Nov. 14.

Yet what happens in Bihar, the great test kitchen of India, will soon be replicated throughout the country. As the state’s voter verification campaign draws to a close, ECI officials have directed their state-level counterparts to prepare for a nationwide SIR before the end of the year. On Monday [Oct. 27, depending on when we publish], SIRs began in 12 additional states and territories collectively home to half a billion voters.

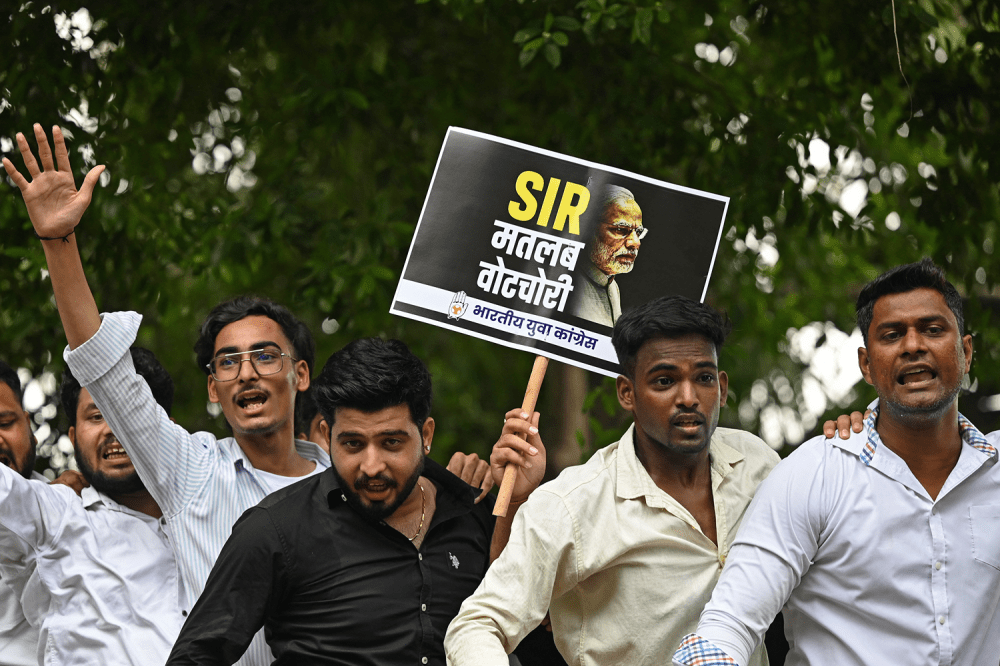

Ahead of the gargantuan task of verifying citizenship for 1.4 billion people, which some critics argue could disenfranchise up to 90 million Indians, events in Bihar snowballed into a contentious national issue. In August, Rahul Gandhi, the parliamentary leader of the opposition and a prominent member of the Indian National Congress party, led a march through Bihar to protest against the SIR. The leader of the southern state of Tamil Nadu also flew to Bihar to take part in anti-SIR rallies, despite the fact that his party—which espouses South Indian regionalism—has scant electoral prospects in the northern state.

Bihar’s voter verification campaign has become the latest struggle to preserve what civil society activists and opposition parties see as the promise of democratic legitimacy in India. “This is a national exercise now. This SIR is going to other states, and [opposition parties] know that they have to build this national campaign to defeat this,” said Pushpendra, a vice president for the PUCL in Bihar.

Ashutosh Kumar Pandey contributed reporting from Bihar.

The post India Is Disenfranchising Millions of Voters appeared first on Foreign Policy.