The license plate on the Jeep Cherokee reads WAMPUM.

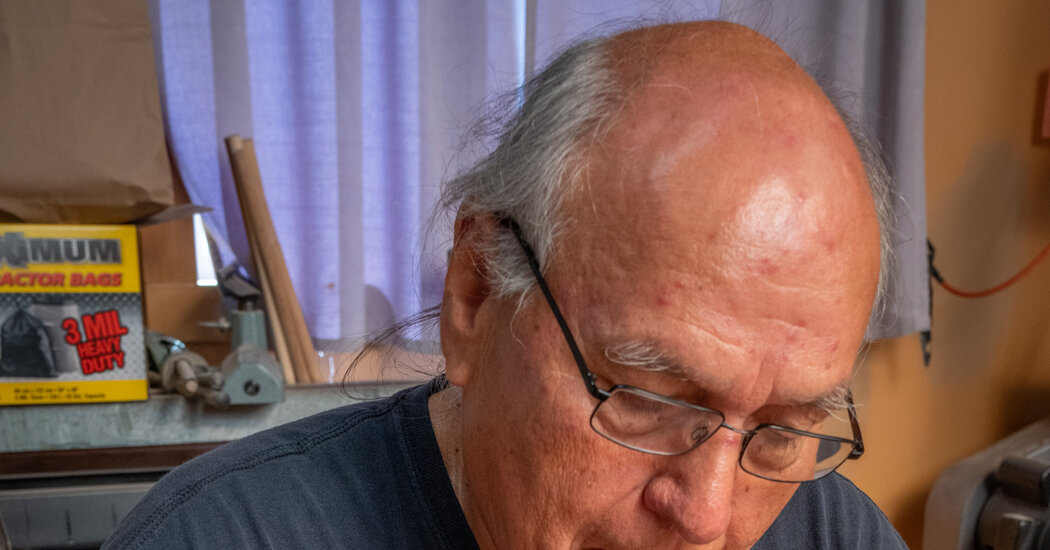

And the man who owns it — Ken Maracle, who also goes by his Cayuga name, Haohyoh — is widely acknowledged to be one of the premiere practitioners of the centuries-old craft of creating wampum, strips with geometric patterns woven in purple and white beads.

While there is a common misconception that wampum was Indian money, it primarily was used in the negotiation and confirmation of agreements among Indian nations and between them and colonial authorities. Mr. Maracle’s belts are close copies of those traditionally created in the Great Lakes region.

“We taught your ancestors diplomacy,” Mr. Maracle said during an interview at his studio on Manitoulin, an island just off the Canadian coast of Lake Huron. He has spent nearly 40 years creating belts that now are owned by collectors and museums such as the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington and the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec.

And the color purple, one of the natural shades of the shells traditionally used to create wampum beads, has apparently bled into the rest of his life, too.

Mr. Maracle, a vigorous 74-year-old, emerged from his home on a recent morning wearing a purple hoodie bearing the names of his hometown, Ohsweken, and the surrounding Grand River Reserve, an area in southern Ontario inhabited by members of the Six Nations Confederacy, an amalgam of the nations of the Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, Mohawk, Tuscarora and Mr. Maracle’s own Cayuga.

Purple also is the dominant color in Mr. Maracle’s studio, a small building across the driveway from the house he shares with his partner, Melinda Trudeau, a school bus driver. Some of his finished belts, which hang on a rail in the studio, incorporate bold purple shapes, or white shapes outlined in purple.

On his worktable were two purple-and-white quahog clam shells from Long Island near New York City, the traditional source of the hard shells used for purple and white wampum beads. Mr. Maracle still uses quahog beads for important commissions, but he also has purple and white glass beads, separated on two paper plates in his studio, for more everyday creations.

He sat down at his worktable in front of a homemade loom: 11 strings of a synthetic version of deer sinew that had been stretched taut between two bits of blond wood and clamped to the table with a vice.

“It’s a friendship belt,” he said, referring to the glass-bead piece that was about halfway done.

At the left end of the loom was a blocky human figure connected to a purple line that, once Mr. Maracle wove some more, would reach another human figure at the opposite end. Belts can be as long as seven feet and as wide as two feet, but this one, he said, would be about 23 inches long and 3.5 inches wide when it was completed.

Mr. Maracle picked up a large needle, designed for stitching leather, that had a length of cotton thread attached. He speared some purple and white glass beads, using the middle finger of his right hand to push the beads into place between the stretched sinews. That finger has had a callus on its tip for years, he said — “some people use the middle finger for other purposes, but for me, it’s this one.”

Counting, he said, is key. Next to a pair of purple scissors in front of the loom was a chart that he often uses to record where the purple beads should go. (He has laminated versions of charts for belts that he creates frequently.)

Once his needle had reached the far side of the belt, he moved it back through the taut sinews to position the beads more securely. “Over, under, over, under,” he said.

A large belt with a complicated pattern can take as many as 90 hours of focused work, he said, and may involve as many as 13,000 beads. Mr. Maracle said the effort required could be exhausting.

“People don’t realize what it takes out of you,” he said of the craft, adding that it could take a toll on the spirit.

When asked about the finished belts, Mr. Maracle took up a few that hung nearby and began to tell their stories, usually connected to historic events and tales popular among the Haudenosaunee — the name that Confederacy members use for themselves rather than the old term, Iroquois.

“This one, the Prophecy Belt, has the Peacemaker on it,” Mr. Maracle said, pointing to a human figure with a long cross shape rising from its head. In Haudenosaunee legend, he said, the Peacemaker helped create the Great Law of Peace, the set of principles on which the Confederacy was founded.

Mr. Maracle said he knew of about 400 historic belts, and he had reproduced 54 of them — “the rest are for another lifetime.”

Beads of Diplomacy

There is one piece that wampum experts refer to as Mr. Maracle’s masterwork: his interpretation of a belt whose formal name is the 1764 Covenant Chain Wampum Belt Delivered at Niagara by the British to the Western Nations. The original was made by artisans hired by British authorities, who presented it during peace negotiations with 2,000 representatives of 24 different Indigenous nations.

Mr. Maracle was commissioned by the Canadian Museum of History to recreate the piece, which had disappeared at some point in the historical record, so he had to rely on archival sketches and written descriptions. When he delivered the completed belt to the museum in 2016, Jonathan Lainey, a noted wampum expert, was working there.

Such belts, Mr. Lainey said in a recent interview, were often displayed during council meetings and exchanged when agreements were made — which was why the 2013 exhibition he curated at the McCord Stewart Museum in Montreal, where he now works, was titled, “Wampum: Beads of Diplomacy.”

“It was important that everyone hearing the words could actually link these words to the belt,” said Mr. Lainey, a member of the Wendat, another Indigenous nation that traditionally used wampum, explaining one reason wampum beads have been called “talking beads.”

Such a connection actually played a part in a 2024 decision by the Supreme Court of Canada, which accepted wampum as evidence that the government had not fulfilled its promises in certain 19th-century treaties.

“In wampum,” said Alan Ojiig Corbiere, an assistant professor of Indigenous history at York University in Toronto, “we have a set of symbols that are what people would call geometric today, and that others would call abstract. But these symbols that are on the belts, they ran from the Eastern Seaboard to the Mississippi.”

‘The Lightbulb Comes On’

As a child, Mr. Maracle said, he did not learn much of his people’s history.

“I grew up with my mother and grandmother,” he said. “My mom spoke Mohawk at home, but she didn’t teach it to me, because she’d been beaten at school for speaking it.”

For many years, he worked outside the reserve as a machinist at a die-making factory in Burlington, Ontario. And in 1988, he was assisting with security at a display of wampum belts that had been returned to the Confederacy when, he said, “an elder came to this one belt, looked me straight in the eye, and he says, ‘What’s this belt?’ And I told him I didn’t know. And he just pointed at me. He said, ‘You should.’

“That’s when the lightbulb comes on,” Mr. Maracle continued. “You know what you’ve been put here for, for sure.”

Several people have helped along the way. He has a framed photograph in his studio of Jacob Thomas, a longtime chief of the Cayuga who became the head of the Confederacy in the 1970s.

“Jake made his own looms and taught me how to do it,” Mr. Maracle said. “If he’d been an engineer, he’d have been a pretty good one.”

Mr. Corbiere, himself an Anishinaabe from Manitoulin Island, has advised Mr. Maracle on the recreation of historic belts, including the 1764 Covenant Chain wampum.

Mr. Maracle also credits his own training as a machinist for his precision.

“I once took something up to my boss there and asked him if it was good enough,” he said. “He handed it back to me and said, ‘Would you buy it?’ That’s now something I say to my students in my wampum workshops.”

The Wampum Shop, Mr. Maracle’s main sales outlet, is located in Ohsweken and run by Rhonda Maracle, his business partner and wife (they are separated).

She sells glass bead pieces for 150 to 1,800 Canadian dollars ($110 to $1,290), while complicated belts made with quahog shell beads start at 30,000 Canadian dollars.

Wampum Magic

While he was working on the friendship belt in his studio, Mr. Maracle described his attempts to make quahog shell beads both by trying out traditional methods and using more modern tools.

He has a lapidary saw to cut the shells into the approximate desired size and shape, and he has found that a carbide drill — like the ones he used as a machinist — is best for boring holes into the shells. He buffs the finished beads with a coarse sandpaper and then polishes them with a smoother one.

But these days, as often as not, he buys finished shell beads from Harry Wallace, a friend and the chief of the Unkechaug Indian Nation on Long Island.

In 1994, Mr. Wallace founded a bead-making company called Wampum Magic in Mastic, N.Y. Its aim, he said, was “restoring the wampum trade to native people,” as well as making the belts more affordable. When he started the business, he noted, a single bead might have cost as much as $12; now some are sold for $2 or even less.

Mr. Maracle also sometimes speaks about the less technical aspects of his craft. While he works, he said, he often listens to a cassette tape he once made of Chief Thomas talking about Haudenosaunee stories and beliefs.

And, he said, “I sometimes put tobacco next to the belt I’m making,” because the traditional Haudenosaunee offering helps him to put “good thoughts” into his creation.

Over the years, Mr. Maracle said, the manual nature of the work has helped him cope with some difficult losses, including the deaths of his mother, a brother and a grandson.

“We haven’t got the answers to our great losses,” he said. But solving the smaller problems presented by his art, he said, is “what you might call therapy.”

Tony Cenicola is a Times photographer.

The post His Wampum Creations Help Keep a Centuries-Old Craft Alive appeared first on New York Times.