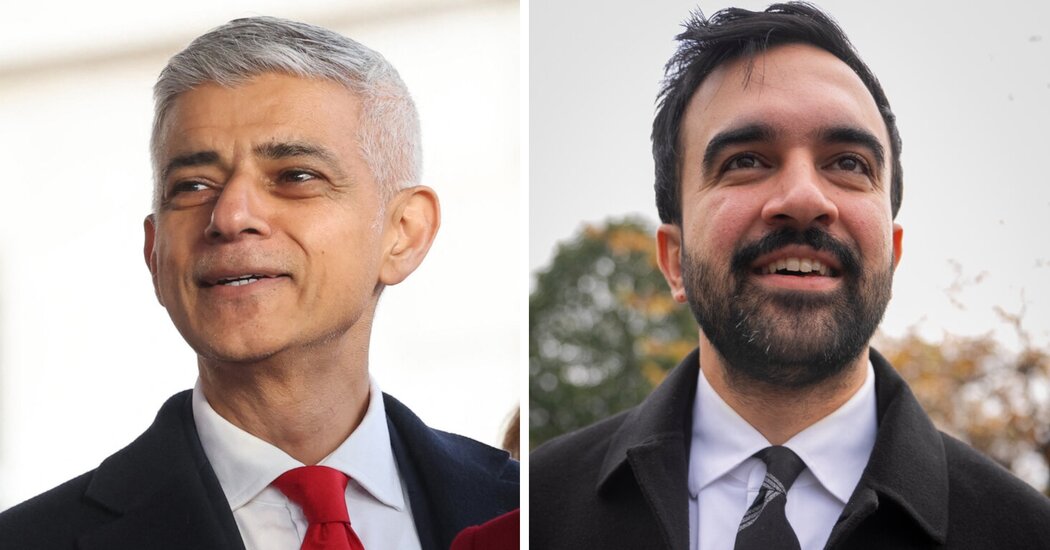

The worldviews of two ambitious, left-leaning Muslim politicians were shaped nearly a decade ago during a year of political turmoil.

In May 2016, Sadiq Khan became mayor of London as Britain voted to withdraw from the European Union, a retreat from global influence fueled in part by anger about migration. That same year, the presidential campaign of Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont inspired Zohran Mamdani, this year’s Democratic candidate for mayor of New York, who joined a generation of progressive activists energized by the senator’s embrace of democratic socialism.

Since then, the men have been living in separate political worlds an ocean apart. Mr. Mamdani proudly champions the progressive left’s agenda, while Mr. Khan has governed as an establishment centrist.

But both have been thrust into prominence — and sometimes attacked in the same breath — as they navigate the nationalist and xenophobic movements that have built across the United States, Europe and beyond. Both have had to increase their personal protection in response to the threats.

If Mr. Mamdani is elected mayor of New York on Tuesday, the two largest cities in Britain and the United States would be led by liberal, Muslim sons of immigrants, both of whom would have risen to power in part by resisting a rightward lurch in their countries.

“We’re in a moment of populist, far-right uprising in both countries. And the center left has had the stuffing knocked out of them,” said Matthew McGregor, the chief executive of 38 Degrees, a progressive London-based think tank. And yet, he added, “Sadiq and Zohran are unusual and inspiring in a way in which they are seeking to use the power of their respective cities to drive progress forward.”

Their political arcs are similar. Mr. Mamdani has made affordability the centerpiece of his efforts to win City Hall. Mr. Khan has focused on affordable housing, public transportation and environmental initiatives like curbing traffic congestion and preserving air quality.

And they both have become targets of vitriolic attacks by President Trump, who won the White House for the first time in 2016. The president has called Mr. Mamdani a “pure communist” and Mr. Khan a “stone cold loser.” His followers say the successes of the two men foreshadow the end of Western civilization.

But in many ways, Mr. Mamdani and Mr. Khan are as different as they are similar.

Mr. Khan was born in London to Pakistani working-class immigrant parents and lived in public housing with his seven siblings — an upbringing that inspired his approach to politics. Mr. Mamdani, who immigrated to the United States from Uganda as a child, is the son of a university professor and filmmaker and has described his childhood as “privileged.” His father’s writings and teachings helped inform his democratic socialist identity.

They also are from different generations. Mr. Khan, 55, has spent more than two decades in office as a centrist, establishment figure from the country’s Labour Party. Mr. Mamdani, 34, engineered a long-shot primary victory in June that upended assumptions about New York’s electorate; inspired young, leftist voters; and built a multiracial coalition.

The two men have spoken only once, and only briefly, according to senior advisers for both leaders. During their conversation, Mr. Khan congratulated Mr. Mamdani for his victory in the Democratic mayoral primary and expressed his pride in seeing a young talent achieve political success.

The senior adviser for Mr. Mamdani said his team had remained laser focused on the campaign in New York and had not yet plotted out a working relationship with the mayor of London or of any other global city. People close to Mr. Khan said that he had been privately impressed by Mr. Mamdani’s political skills, but that he had not spoken publicly about him. The advisers and people all spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss political matters.

Neither Mr. Mamdani nor Mr. Khan agreed to discuss how they approach similar issues confronting their cities.

Conservative and Democratic leaders have described Mr. Mamdani as too far left to appeal to voters outside deep-blue New York City. His campaign promises include free buses, universal child care and a rent freeze for millions of New Yorkers. His rivals have described the ideas as fanciful and fiscally dangerous.

By contrast, Mr. Khan has sometimes been criticized by left-wing voters as being too centrist. During his first mayoral term, he vocally criticized the Labour Party’s leader at the time, Jeremy Corbyn, who proudly identifies as a socialist and is a veteran of radical left-wing protest movements.

Both Mr. Mamdani and Mr. Khan have seized on the diversity of their cities to shape their campaigns and approaches to governing. But they have faced different pressures from voters, especially on the issue of what to say about the war in Gaza and the treatment of Palestinians.

Mr. Khan called for the British government to recognize a Palestinian state months before it made the decision, following pressure from the political left and large pro-Palestinian demonstrations in London. In September, he described Israel’s actions in Gaza as a “genocide.”

Britain’s control of Palestine in the decades leading up to World War II and its role in the creation of the state of Israel has led to broad popular support in London and other cities for Palestinian self-determination.

The Palestinian issue has been one of the most difficult for Mr. Mamdani to navigate. Much of his appeal to many New York voters is the result of his unwavering support for Palestinian rights and early call for a cease-fire in the war. But his critics say that he is anti-Israel and not sympathetic to the city’s large Jewish population.

In an interview on Fox News last month, Mr. Mamdani dodged a question about whether Hamas should be forced to disarm and abandon leadership, saying he remained focused on the issue of affordability in New York. Representative Elise Stefanik, Republican of New York, a frequent critic of Mr. Mamdani, called him a “jihadist,” something his campaign called xenophobic and dangerous.

The politicians’ experiences, in part, reflect the demographics and the politics of their respective cities.

A recent survey of the religious populations in New York found that roughly a half-million of its residents, or about 6 percent, belong to a mosque. The Jewish population is larger, double by some estimates.

Like New York, London is ethnically and religiously diverse. In the 2021 census, 15 percent of its residents identified as Muslim, making Islam the city’s second-largest religion after Christianity. Less than 2 percent of people in the city are Jewish.

Mr. Khan has courted London’s diverse cultures during his three terms. He has celebrated his Muslim heritage and joined public celebrations for the festival of Eid. He also chose to be inaugurated in 2016 at a Christian cathedral in a ceremony attended by civil rights campaigners, has marched in official Pride parades and voted in favor of same-sex marriage in his previous role as a lawmaker.

“Being the son of a bus driver was probably more prominent during the campaign than him being Muslim or being the son of Pakistani immigrants,” said Uma Kumaran, a British Sri Lankan member of Parliament who helped lead Mr. Khan’s first mayoral campaign.

Perhaps the biggest similarity between Mr. Khan and Mr. Mamdani is the vitriol they inspire on the right in both countries.

Stephen K. Bannon, Mr. Trump’s onetime chief strategist, has repeatedly raged about the two men, accusing them of being part of a “red-green alliance” between Democrats and “radical Islamists,” and he has said they are “Marxists.”

A Fox News host suggested this past week that New York under Mr. Mamdani would turn into London — a thinly veiled allusion to the city’s large Muslim population and fears about street crime.

A White House spokeswoman, Abigail Jackson, said in a statement that “London and New York City are microcosms of what can happen when left-wing policies are allowed to reign, unchecked by common sense,” and added that “America’s cities should look toward President Trump’s law-and-order policies, not the liberal agenda embraced by socialists like Mamdani.”

The attacks have dogged their political lives.

Four days before the 2016 London election, Mr. Khan’s main opponent from the Conservative Party wrote an article that accused him of antisemitism and claimed that his election would amount to “aggressive socialism entering Britain though the back door.” It was illustrated with a photograph of a bus that was bombed in 2005 during London’s deadliest terrorist attack. Mr. Khan won the final vote by 13 percentage points.

Asif Hussain, a former senior adviser to Mr. Khan and deputy director on his 2024 re-election campaign, said the mayor’s race that year brought a “fever pitch” of far-right vitriol against him. Even criticisms of his environmental and public transit policies were tinged with xenophobic, anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Mr. Khan has been a political target for the right-wing Reform U.K. party, which has blamed him for crime in London and claimed the city is “lawless.” He has countered the criticism by highlighting a drop in violent crime and denouncing opponents for spreading misinformation.

Mr. Mamdani has received attacks from members of his own party. When a conservative radio host suggested that Mr. Mamdani “would be cheering” another Sept. 11-style terrorist attack, Andrew Cuomo, the former Democratic governor of New York and Mr. Mamdani’s leading opponent in the mayoral race, quipped, “That’s another problem.”

Mr. Khan and Mr. Mamdani have so far refused to back down in the face of the attacks. Mr. Khan recently accused the American president of fanning “the flames of divisive, far-right politics.” Mr. Mamdani has said that Mr. Trump’s election plunged the United States into “a period of political darkness” and that his opponents’ messaging shows that anti-Muslim sentiment is acceptable in public discourse.

If Mr. Mamdani is elected on Tuesday, he and Mr. Khan may find new reasons — despite their differences — to cooperate as they navigate the increasingly angry political climate.

“London is a major capital in the world. What Sadiq says is of consequence. What the president of the United States of America says is also of consequence,” Mr. Hussain said. “And I think one thing that Zohran will need to be aware of is, once you’re in that position, it’s not just a regional, mayoral role. It’s a global role.”

Maya King is a Times reporter covering New York politics.

Michael D. Shear is a senior Times correspondent covering British politics and culture, and diplomacy around the world.

The post The Far Right Targets Their Similarities. Their Differences Define Them. appeared first on New York Times.