You’ve probably seen gerrymandered congressional maps with snaking, winding, twisting districts drawn to give one party an advantage.

In the not too distant future, it might be possible to imagine even crazier maps.

For decades, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which has been interpreted to require the creation of majority-minority districts, has effectively put a ceiling on partisan gerrymandering, especially in the big diverse states. It hasn’t merely been a limit on gerrymandering; it’s the only meaningful federal limitation on partisan gerrymandering.

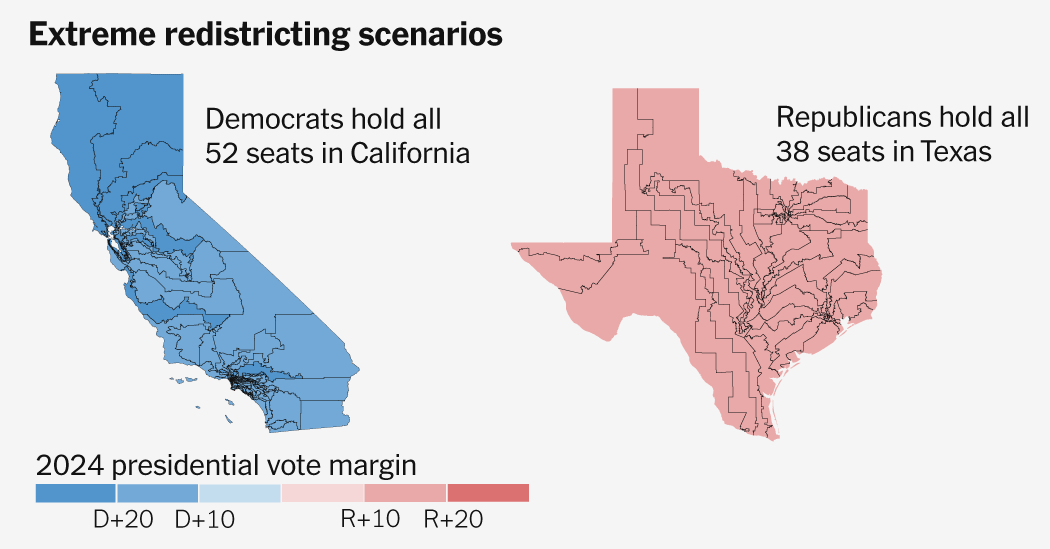

So if the Supreme Court strikes down Section 2, as it is considering, any equally populated House district is fair game, at least as far as federal law is concerned. There would be no federal law that might deter a 38-0 Texas congressional map that unanimously elected Republicans, or a 52-0 map in California with nothing but Democrats.

To be clear, such extreme gerrymanders are unlikely for a host of reasons. But the point isn’t that these two extreme maps are likely; it’s that they might soon be legal. And while states may not go this far, they may nonetheless be tempted to push toward more extreme maps than ever before.

As long as Section 2 remains, a maximal partisan gerrymander isn’t likely to pass legal muster in any of the largest states in the country. Most obviously, Section 2 prevents Republicans from breaking up every Democratic district in red states with a large enough nonwhite population. In Missouri and Tennessee, for instance, Republicans broke up the districts representing majority white but Democratic-leaning cities like Kansas City and Nashville, but had to preserve the Democratic districts in St. Louis and Nashville with large Black populations.

Without Section 2, Republicans could legally break up any majority-minority district in a red state. Take Houston, which currently has both majority Black and Hispanic congressional districts. Without the law, these areas could be sliced up and divided among multiple pinwheel-like districts that stretch far into the countryside.

Less obviously, Section 2 prevents Democrats from diluting overwhelmingly Democratic majority-minority districts, whose voters might otherwise be spread out to flip red districts. In California, for instance, a maximal partisan gerrymander might split Democratic-leaning Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Los Angeles among dozens of districts that stretch to the more conservative parts of the state.

Again, these exact maps are unlikely; they are best seen as illustrations of how urban districts can be — and often are — diluted for partisan purposes. Many congressional incumbents would balk at maximum gerrymanders. They don’t want to represent incoherent, pinwheel-like districts. Even if they were fine with such districts in theory, the new lines would probably deprive them of their traditional bases of support. Swing state legislators might not support such extreme maps, either. Even under the current rules, ongoing efforts to redraw maps in states like Kansas, Indiana and Illinois have sometimes struggled to find the requisite votes.

But while such extreme gerrymanders might still be unlikely, they’re no longer implausible to contemplate. And there is a lot that states could do just short of creating unanimous districts, especially as President Trump’s push for mid-cycle redistricting has sparked an escalating redistricting war.

Math won’t get in the way, either. As a rule of thumb, a state’s congressional map can be drawn such that each district roughly reflects the overall vote statewide. In a state like Texas, it ought to be possible to draw 38 approximately Trump +14 districts. In California, 52 districts that would have voted Harris +20 ought to be possible as well. In the two demonstration maps, all 38 districts in Texas voted for Mr. Trump in both 2020 and 2024, including by at least 10 points in 2024. Ms. Harris won by at least 15 points in every California district.

And if Texas Republicans think Trump +14 is a hair too vulnerable — they probably would, as most Republican districts today are even safer — they could draw a 35-3 map with the red districts at approximately Trump +19. Either way, it would represent an enormous shift from 2024, when Democrats won 13 seats in Texas and Republicans won nine in California.

In the short term, Republicans would be better positioned than Democrats in an all-out redistricting war. There are simply more Democratic-held seats in states where Republicans exercise full control over the redistricting process than the other way around. More blue states have constitutional limitations on gerrymandering, like nonpartisan commissions. And blue state courts have tended to enforce constitutional provisions against gerrymandering more vigorously than red state courts.

Over the longer term, however, Democrats could level the playing field by amending blue state constitutions to allow partisan gerrymandering, whether in response to mid-cycle redistricting or lastingly. Constitutional amendments are not easy to enact, but Democrats seem likely to pull this off in California, and they are attempting to do so in Virginia as well. In the years ahead, New York or Colorado could follow a similar path. If blue states manage to do so, Democrats could potentially eliminate as many seats as Republicans, even if the Supreme Court strikes down Section 2.

Either way, the House of Representatives would become significantly less representative, whether in terms of the diversity of the seats or its responsiveness to public opinion overall. The number of swing districts could plunge. And the congressional map might look stranger than ever before.

California 2024 presidential election results by congressional district are from The Downballot. Extreme redistricting scenario congressional district results are from Dave’s Redistricting. Current California districts reflect boundaries as of Oct. 31. Current Texas districts reflect boundaries enacted in August as part of mid-cycle redistricting.

Nate Cohn is The Times’s chief political analyst. He covers elections, public opinion, demographics and polling.

Jonah Smith is a data journalist at The Times, specializing in computational reporting and analyzing large data sets.

The post Future of Gerrymandering? Here’s How Weird Things Could Look. appeared first on New York Times.