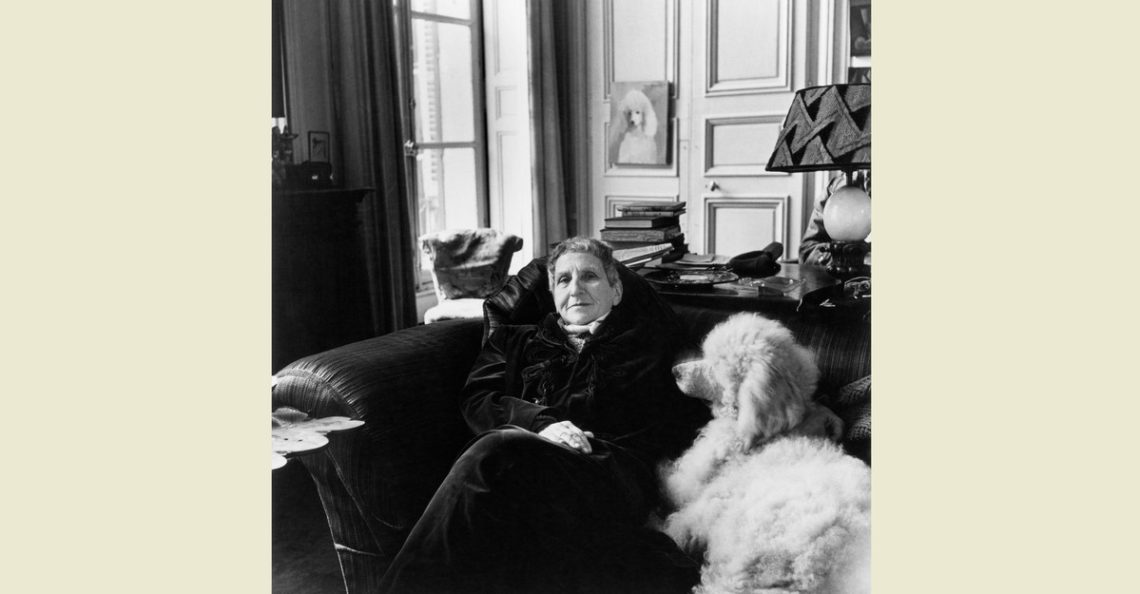

What to do with Gertrude Stein? Decades after her death, she still bestrides the literary landscape like a mastodon, impossible to ignore, determined to take up space. A confrere of Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Ernest Hemingway (until she fell out with the latter), she was an enigmatic creature—overtly masculine, her hair shorn like a Roman emperor’s, her stout body clad in corduroy robes and, later, in tweed suits designed by her friend Pierre Balmain. Stein assiduously created her own mystique; she had every wish attended to by her devoted companion of nearly four decades, the mustached Alice B. Toklas, who was a wizard in the kitchen and kept a grim watch over the many inquisitive visitors to their salons at 27 Rue de Fleurus in Paris. For me, the essential question about Stein has always been and continues to be this: Does her enduring reputation owe more to her importance as a daring modernist, in the league of James Joyce and T. S. Eliot, or to her penchant for marketing herself as a genius, despite a woeful inability, with one or two exceptions, to write readable prose?

Francesca Wade’s new book, Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife, is the latest entry in a trove of essays, critical studies, and biographies about this eccentric and dominating personage. Wade’s first book, Square Haunting, focuses on a group of female intellectuals, including Virginia Woolf, who moved to London’s Mecklenburgh Square in search of greater freedom, and showcases her skills as a researcher and writer. It has a clear thesis and a fluid trajectory, and carries its erudition lightly. An Afterlife is equally well researched—Wade had access to Stein’s voluminous papers, stored at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library—but is less assured and less sonorously written; much of the ground that it covers is familiar, and some of the scholarly details she exhumes seem tiresome rather than revelatory. Indeed, the most intriguing thing about this biography may well be Wade’s effort to prove that Stein was the exceptional human being she took herself to be.

Stein obscured the answer to the question of her reputation by snipping her origin story—the path she took from vulnerable striver to mythic figure—out of the official portrait. “Gertrude hated her own past,” Wade quotes Toklas as saying. “She referred to it as little as possible.” Relatively little is known about Stein’s early influences, the kind of childhood she had, how she felt about her mother and father. And yet, despite her grandiose, characteristically ungrammatical assertions of superiority and uniqueness—“think of the Bible and Homer think of Shakespeare and think of me”—Stein began life in the same mundane circumstances as everyone else.

She was born on February 3, 1874, in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, the youngest of five children, and five years later her German Jewish family moved to Oakland, California. Stein’s mother, who seems to have been a mild, negligible presence compared with her harsh, critical father, died of cancer when Stein was 14. Her father died three years later from a sudden stroke, leaving a pile of unpaid debts. During the intervening years, Stein’s high school burned down, and she took to spending her days at various libraries and wandering through the city in the evenings with her artistic older brother Leo. Their older brother Michael proved to be talented with money and provided his sister with a monthly stipend that allowed her not to work. In the spring of 1892, Stein and her sister, Bertha, moved to Baltimore, where they had been invited to live with their mother’s sisters. Stein enrolled at the Harvard Annex, which was renamed Radcliffe College a year later.

The eminent psychologist William James invited the 19-year-old to join his seminar at the Harvard Psychological Laboratory. Stein conducted experiments under James’s supervision, but quickly tired of studying her subjects’ responses and preferred talking with them and tracking their characters. “She wrote up her findings,” Wade writes, “in an 1898 paper titled Cultivated Motor Automatism, an idiosyncratic document which reads more like notes for a novel than an academic treatise.” Stein enrolled at Johns Hopkins Medical School, the first such institute in the country to accept women, but did not do well and canceled her plans for postgraduate work, later claiming that she was “openly bored” at medical school. Europe and Leo were calling her.

Within minutes of arriving in Paris in 1903 and settling with Leo near Montparnasse, Stein hurled herself into the center of the thriving avant-garde art world. She picked up and dropped people with ease, including Virgil Thomson and Mabel Dodge, winnowing down her circle to one of adoring intimates; anyone who so much as questioned her talent or primacy was left by the roadside. Leo led her to the work of the aging Paul Cézanne, whose Portrait of Madame Cézanne would eventually hang over her desk. Stein later credited Cézanne for inspiring her own abstract style—“a way of writing,” as Wade describes it, “that would depart from the two centuries of realist fiction she had devoured since childhood.” The artist made her realize, she told an interviewer, that “it was not solely the realism of characters but the realism of the composition which was the important thing.”

The siblings also became regulars at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard, purchasing impressionist works by Claude Monet and Edgar Degas as well as more innovative ones by Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh. After being introduced to Picasso, Stein quickly developed a close relationship with him, discussing his work in his cluttered studio, giving him loans, and purchasing his paintings. Wade notes that he “showed his appreciation by acknowledging her as an equal. An envelope, containing one of the many notes they exchanged in these years, is addressed to ‘Gertrude Stein, Man of Letters.’” She also became enamored of stranger thinkers, such as the misogynistic, anti-Semitic Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger, who held cockamamie ideas about gender and genius that seemed to be right up Stein’s alley. (He committed suicide at age 23.)

In between cultivating friendships with expats and arranging Saturday-night salons, Stein delved into her own writing, typing with one finger at a time and abandoning “conventional crutches—plot, scenes, linear time”—for which she substituted the heavy repetition, illogical phrases, and often-inchoate details that make up the bemused anti-narrative of her near-1,000-page novel, The Making of Americans. Originally envisioning a family saga, she ultimately aimed to recount the history of everyone who had ever lived. During the 10 years it took her to complete the book, she paid for the publication of a collection of stories called Three Lives, perhaps the most supple of her experimental works, which was noticed and praised by critics.

In the winter of 1907, Toklas entered Stein’s life, gradually transforming it. One might well ask whether Stein’s popular reputation—as unlikeable but charismatic, arrogant but disarming, self-serious but witty—would have developed without Toklas beside her: typing up her manuscripts, feeding her, encouraging her, admiring her, holding her up to herself and to the world as a mind unlike any other. According to a friend of Stein’s, she could not “cook an egg, or sew a button, or even place a postage stamp of the correct denomination on an envelope.”

Along with her numerous detractors, including Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound, who once wrote in his anti-Semitic fashion that she “writes yittish wit englisch wordts,” there were people, such as Marianne Moore and Katherine Anne Porter, who responded positively to Stein’s intentionally hermetic style of writing. But her rapacious ego was not satisfied with a small reputation; she remained hungry for a wider audience and greater renown—more “gloire,” as Stein liked to say—to which end she conceived of writing a book in a more conventional, mainstream style. This would become The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, which Wade describes as “a joke, a myth, an audacious act of knowing artifice.” Channeling what is ostensibly the clear, witty voice of Toklas, Stein creates an extended homage to herself, settling scores, praising friends, describing nights out at the Russian ballet and stimulating dinners at home, and invoking a household that runs as smoothly as it does because of Toklas’s domestic skills. In this way, she succeeded in writing about her charmed life without giving away anything of herself.

The second half of An Afterlife, which begins with Stein’s death, is where Wade comes into her own, using hitherto unavailable material to develop fresh ideas about the relationship between Stein and Toklas, which “complicate the public image of mutual devotion.” Both of them were unobtrusively Jewish—Toklas converted to Catholicism before she died—and patriotic Americans, although they continued to live in their beloved France even after the Nazis occupied Paris. The thorny topic of how this “pair of elderly Jewish lesbians,” as Janet Malcolm called them, survived under the nose of the Nazis, and how much this was due to their interactions with collaborators, was taken up by Malcolm in her uncommonly searching dual biography, Two Lives; it is explored again by Wade. The details are somewhat incriminating: Both women maintained a close friendship with Bernard Faÿ, a higher-up in the Vichy government, and Stein was a vocal supporter of its leader, Philippe Pétain. Perhaps this is how she managed to avoid having her ID and ration card stamped “Jew.” Even with these new details, however, it is hard to see her and Toklas as anything other than both shrewd and lucky.

Wade does a lot of pointillist deep diving in the Yale archives, seeking to reexamine both the Stein-Toklas partnership and the value of Stein’s writing. What becomes abundantly clear is that Toklas was far more than the silent sycophantic partner. She was a power in her own right, brainy and perceptive, given to quick opinions (she seems to have taken an immediate dislike to Hemingway) and immovable convictions (lobster should be “boiled furiously”). There seemed to be an element of sadomasochistic play in their relationship, of withholding and succumbing, that contravenes the popular sense of an unremitting dominant-submissive dynamic.

It was after Stein’s death that the two central questions about her life—her artistic influence and her relationship with Toklas—merged. Toklas went on to fiercely uphold the author’s legacy, honoring Stein’s apparent desire to be understood while at the same time respecting her equally strong wish to remain elusive. Despite Stein’s drilling into her that she could not write, Toklas also published a wildly successful gem of a cookbook that included an infamous recipe for hash brownies.

In the end, I don’t think that An Afterlife succeeds in bringing us closer to a firm answer on the conundrum of Stein’s genius. I came away from reading it with a feeling for Stein’s distinctive intellect and her dizzying thoughts about writing (although many of them sound elementary or close to gobbledygook), as well as her ambition to upend literary tradition by taking prose on a path beyond plain representation. But what Wade calls the “new aesthetic boldness” of her work does not necessarily signify that a successful experiment has taken place. I remember admiring Three Lives when I was young and reading The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas with great relish, but I don’t feel a hankering to reread those books or to go on and read other works by her. Despite Wade’s painstaking exertions on her behalf, it seems to me that Stein is fated to remain an acquired taste, beloved of a few devotees. In the fickle literary firmament, this is not such a small thing, but although it might be enough for some writers, it would not have sufficed for Stein.

The post The Writer Who Wanted Everything appeared first on The Atlantic.