On Sunday morning, for the 12th time, I’m going to ride the Staten Island Ferry out from Lower Manhattan en route to the start of the New York City Marathon.

Every year, I sit on the ferry thinking about all the training I’ve done. I visualize the course and plan the paces I want to run for each mile. I replay specific moments from my hardest workouts. I breathe in through my nose and out through my mouth and I try to relax every muscle in my body, from my metatarsals to my neck. And every year, as I do this, at some point my mind shifts to my father.

He took the same ferry out for the start of the race once, back in 1982. He was 40 years old and coming to the realization that he was gay. He had left my mother and our home in Boston for Washington, D.C. And he was beginning a period of life that included prodigious amounts of alcohol, record-setting promiscuity and little sleep. But running seemed to provide enough centripetal force to hold his life together.

I was 7 years old, and I came south to watch the race. I stood at mile 16 with my nanny and searched for my father in the sea of sweaty people in short shorts as they came down the Queensboro Bridge. My father’s goal that day had been to finish in under three hours, and he came close, missing by less than a minute. It was the fastest marathon he would ever run, and he always said he couldn’t have gone that quickly if I hadn’t been there.

In the years and decades that followed, I took to running. I was a star in high school who wasn’t quite good enough for college. In my 20s, I chased my father’s goal of a sub-three-hour marathon for seven years. Once, I dropped out of the New York Marathon at mile 23, as my father waited at the finish, because my knee hurt. It was, in retrospect, the worst running decision I’ve ever made. Everybody’s knees hurt at mile 23.

But then, eventually I did break three. And I then got even faster and, a few years later, broke 2:40. No one cheered me on with more enthusiasm than him. Until my father turned about 60, and his hips stopped working, we would jog together whenever I spent time with him.

My father’s later years were rough. He stopped running in spite of occasional grand pronouncements about his fitness goals, which he would cast aside by pouring another glass of gin. He often talked about how his heart, made strong from years of marathoning, was the one part of his body that worked well. But eventually that, too, gave out.

His death brought a new intensity to my running, partly as a way to mourn him. I came up with a system that allows me to run reasonably fast without ever making running a bigger priority in life than my job or spending time with my wife and three beloved sons. My father’s trade-offs — in running, but in many other things — defined his life. I would use running to live a different way.

And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve begun to see deep connections between how I train and the way I live and work. The mental process one uses to run faster and the mental process one uses to get through anything hard are connected. Pain has physical causes, but it’s mostly a mental process: We slow in races less because we reach our physical limits than because our minds get scared.

I commute to and from the office most days on foot, logging about eight miles in an hour and 10 minutes that would otherwise have been spent on the subway. When I’m preparing for a race, I run hard workouts on Tuesdays and Thursdays and track my heart rate meticulously. One day on most weekends, I run 20 miles or more.

This summer, I had a streak of seven consecutive weeks where I ran a total of more than 70 miles and less than 72. I keep track of everything in a Google Doc. I know that my body stores the benefits from a workout for about 22 days and that it takes about nine days for me to recover fully from something hard.

I run the same workouts every year and can usually predict my marathon time within a minute or two based on how I’ve done. Through my middle 40s, my marathon time dropped and dropped, until, at 44, I finished one in 2:29. Now, at age 50, I seem to be gradually slowing. The past few months have been particularly trying. I won’t be anywhere near that time on Sunday.

The lessons you learn in the sport — discipline, self-awareness, and understanding of life’s rhythms — can be used to hold off the kinds of demons that tormented my father. I held on tight to running because I came to believe it would both bring me closer to my father and help me avoid becoming him.

I also know that running is not an elixir. My spreadsheets give me an illusion of but not actual control, either of this sport or of life. Running every day creates a small tailwind: pushing forward good habits and helping us clear our minds. The sport helped my father during a dark time in his life, but it couldn’t save him.

But a small tailwind can be overwhelmed by a big headwind, or a nasty gust from the west. I know that eventually I’ll have to stop: My hips will give out, my Achilles might snap, my doctor will notice something wrong. No one runs forever. Some year, at mile 23, I might have to drop out for a real reason.

My father and I never ran a marathon together, but I wish we had, and I wish he would be there to cheer me on Sunday. My children will be there, though, and my 15-year-old son has pledged to run this race with me in three years. And it delights me to know that I’ll be running in the footprints my father left 43 years before as the race begins and tens of thousands of us head up the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge.

It’s an amazing view: You can see so far into the city, and you have so far to run. If you’re in the crowd at mile 16, just after the Queensboro Bridge, cheer as loudly as you can.

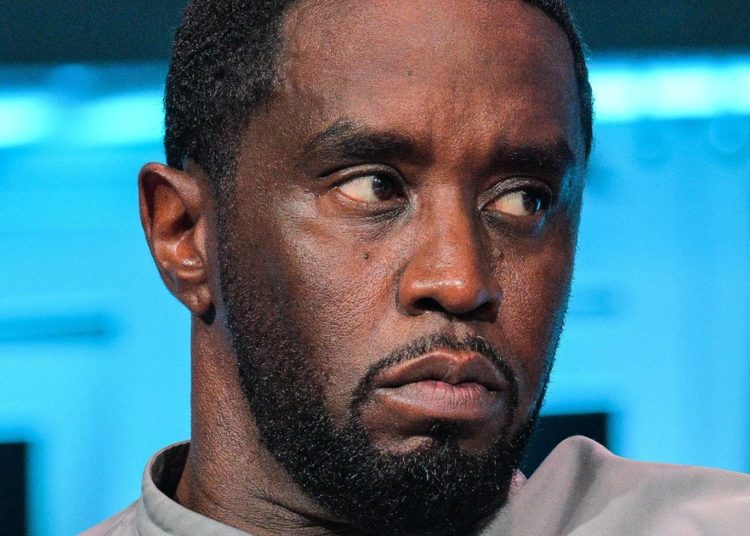

Nicholas Thompson is the CEO of The Atlantic magazine.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post The Way I Run Is the Way I Live appeared first on New York Times.