I. ‘Bunch #2’ (1995)

One afternoon this past September, the artist B. Wurtz, 77, was standing barefoot in the basement of the nearly 200-year-old townhouse on New York’s Lower East Side where he lives with his wife, Ann Bobco, 71, a graphic designer. The space was tidy but crowded, filled with cardboard boxes holding his artworks, which he assembles from mass-produced things that typically end up in garbage cans, junk drawers or recycling bins: buttons, screws, blocks of wood, clothespins, shoelaces. Some of Wurtz’s raw materials were stored here too, including a large number of empty yogurt quarts (Stonyfield, Trader Joe’s European Style) that he’d stacked into a tower. “This is nothing compared to what I go through,” Wurtz said. “I eat yogurt every day.” He once hung the containers from a clothes-drying rack to make a mobile that swayed in the air, like a supermarket Alexander Calder.

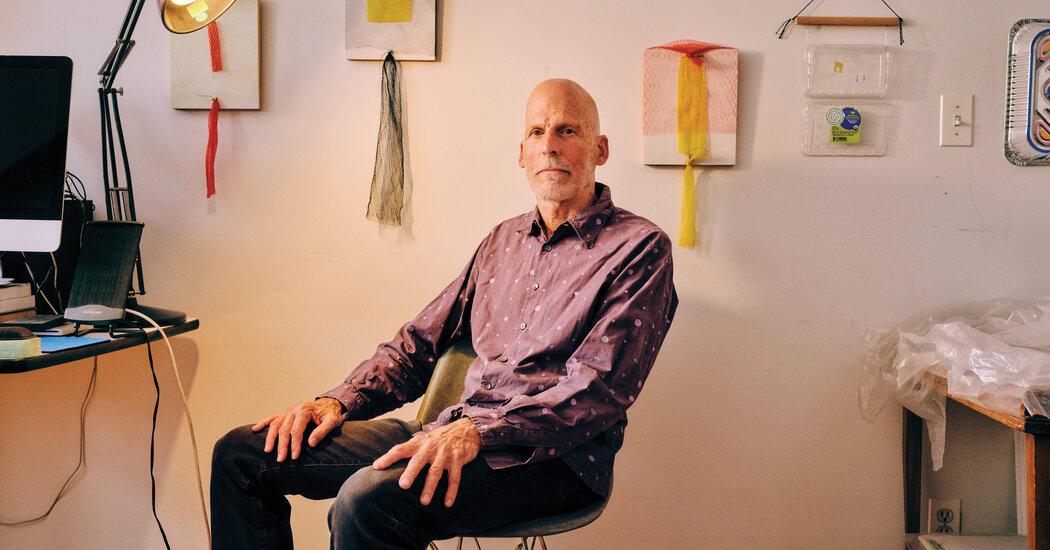

Wurtz was set to premiere his 58th solo show, at the Garth Greenan Gallery in Chelsea. He’s been exhibiting regularly in Manhattan for four decades but remains a cult figure. Tall, slim and bald, he eats well, swims and hasn’t had a drink since college, when some sangria made him realize, “This is a way to try to escape from myself, and I don’t think it’s a good idea.” He’s never had an assistant. For most of his career, he had day jobs — as a gardener, a security guard, a cleaner of 35-millimeter photo slides, a stager of audiovisual presentations for corporate meetings and a paste-up artist for various publications. When he’s not making art, he spends a lot of his time riding around on his bike, seeing art shows.

Many artists have commandeered everyday objects since the beginning of the last century. Pablo Picasso included a hunk of oilcloth printed to resemble chair caning in a still life in 1912 and, soon after, Marcel Duchamp secured a bicycle wheel atop a stool. Duchamp’s readymades, he once said, were “raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist’s act of choice.” Later, Robert Rauschenberg incorporated newsprint, dried grass, lightbulbs and pillows into his Combines, and David Hammons made sculptures from empty liquor bottles and fried-chicken wing bones.

Wurtz has continued this tradition, using banal things to conjure unexpected grandeur. Take, for example, “Bunch #2” (1995), an eight-foot-tall tree with a table base from a restaurant supply store as its trunk. Instead of foliage, its branches hold 41 plastic bags from places like Gourmet Garage and Duane Reade. Wurtz used them, he said, because they were “the most ordinary, overlooked thing I could think of.” In “Bunch #2,” such castoffs take on a stubborn, unlikely beauty: Look at what we throw away, and imagine what could have been.

II. ‘Three Important Things’ (1973)

Next to the computer in Wurtz’s office, on the top floor of his house, is a print of an early drawing: a list he made in childlike cursive in 1973. He was 25, living in Santa Barbara, Calif., struggling to build a career after studying art at U.C. Berkeley. At the time, conceptual art was on the rise, and some artists were writing instructions for pieces they’d never actually make. “The work need not be built,” Lawrence Weiner declared in 1969 in one of the many manifesto-like texts circulating back then. Wurtz’s contribution to this lineage is comically spare. It reads: “three important things 1. sleeping 2. eating 3. keeping warm.”

In high school, Wurtz had made art by placing found objects in boxes; later, he began building sculptures from rudimentary elements. One early effort, “Handbag” (1970), is a purse made of clear plastic sheeting with a bent wire as a handle. He sensed this bare-bones approach had potential — perhaps too much. “I thought: ‘There are so many found objects,’” he said. “ ‘I need to put some kind of rule on this or it’s going to overtake me.’” With his list, he realized, “I already have my subject matter. It’s pretty obvious: It’s about ordinary stuff.”

III. ‘Untitled (“Lock Series” #2)’ (2012)

Though many friends call him Bill, professionally Wurtz has always gone by B. “I really like the fact that this doesn’t give the gender of the person,” he said. In a review of his 2011 survey at the now-closed Metro Pictures gallery in Chelsea, the critic Roberta Smith, writing in The New York Times, admitted that she’d assumed for years he was a woman. “Art, to me, should be about the viewer’s relationship to the artwork,” Wurtz said. “And yes, they’ll probably be curious about the artist. But they could find out later if they want.”

When he was born, in 1948 in Pasadena, Calif., his parents named him William. His mother was “a ’50s housewife,” he said. “She also had a lot of emotional problems.” She was beautiful, “like a cross between Lauren Bacall and Katharine Hepburn, and she was a really good singer.” He had a younger sister with “extreme mental illness,” who died in 2016. His father was an engineer specializing in cryogenics, ultralow temperatures — “extremely bright, also psychologically complicated,” Wurtz said. “He basically was absent. He sort of just ignored me.” But “I did get a lot from him because he was always making stuff.” The family lived in Santa Barbara, and his dad had a workshop in the garage. “He’d give me little scraps of wood, and I would sit on the floor and glue them into little houses and draw doors and windows.”

Some of Wurtz’s most effective works retain the feel of a child tinkering, entertaining himself and perhaps trying to get the attention of his parents. Between 1985 and 2012, the artist made roughly 20 sculptures by screwing simple sliding locks into hunks of wood and, in some cases, adding doorstops as legs. The two parts of the lock are always separated and, while Wurtz tends to talk about his art primarily in terms of aesthetics, these locks are “about frustration or sadness,” he said, because “they’ll never meet.”

IV. ‘Untitled (Romaine)’ (2025)

“I did at one point realize that, with the kind of art I was making, I couldn’t stay in Santa Barbara,” Wurtz said. He needed to go to a big city or to graduate school, so he picked the California Institute of the Arts, a hothouse for the avant-garde in Valencia, in part because the conceptualist John Baldessari taught there. In the early 1970s, Baldessari had made a work with two photos of a pencil, dull and sharp. Beneath those images, he wrote, “I’m not sure, but I think that this has something to do with art.” Wurtz had loved that work, which fit his vision of art arising from the everyday.

At CalArts, he met Bobco and, after finishing school, they moved to Los Angeles and then, in 1985, headed to New York, where Wurtz came into his own as an artist. There was so much ordinary stuff from which to take inspiration, and the city continues to influence him. After the success of the Metro Pictures show in 2011, he took a residency at Dieu Donné, a New York nonprofit devoted to art made with handmade paper, where he created paper works made to resemble plastic bags one might get from a bodega.

The Garth Greenan show, which is on view through Dec. 13, includes a collagraph, a kind of print that Wurtz recently learned to make from another member of Dieu Donné, where he now sits on the board. The process involves placing materials on a plate, running it through a press, then inking it and putting it through the press once more to imprint it on paper. His series includes imprints of mesh produce bags, yogurt container lids and bread clips. Somewhere in each work is an ad for produce — cantaloupes, celery, squash — that he cut out from a supermarket circular. “I like that it could be the 1950s,” he said, “and it would still look like that.”

In many ways, Wurtz’s project represents a nearly half-century-long defiance of the internal logic of contemporary art, a rejection of the big-budget spectacles that have come to define so much of the business. As artists like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst used increasingly large teams of fabricators and assistants, blurring the line between art and luxury, Wurtz went in the opposite direction. In 2021, he was a finalist for a commission to create a permanent piece for a public school slated for construction in the Bronx. “I was going to make it myself for a few hundred dollars,” he said. The official in charge came to him, he said, and explained, “ ‘No, no, there’s a budget of, like, $75,000.’”

V. ‘Untitled (“Pan Painting”)’ (2022)

Wurtz also sometimes picks up disposable aluminum roasting pans when he’s at the market, then fills their embossed patterns with different shades of paint, as if coloring in prefab, postwar geometric abstractions. Whenever manufacturers alter their designs, he’s spurred to make new paintings. He’s done hundreds of “Pan Paintings” since 1990.

On their own, these pans are the opposite of collector’s items. They’re flimsy, unintended for reuse. The painted pans, he said, “made me think of flowers. A flower is a very stable thing. But it could also be crushed.” When several are displayed together, they look resplendent, but they can also be vaguely disorienting — they become something else. Like all Wurtz’s works, they shift one’s perspective about the very nature of objects: what they’re for, how long they’re meant to last and which ones have the right to be beautiful.

Photo assistant: Colin Smith

The post The Artist Whose Muse Is the Hardware Store appeared first on New York Times.