Even from the back, Patti Smith was unmistakably Patti Smith. Standing on a downtown-Manhattan sidewalk on a late-summer afternoon, she wore loose jeans rolled at the cuff, white high-tops, a black blazer, and—on a cool day for August, but still an August day—a wool cap over her long gray hair. We had arranged to meet at a gallery owned by friends of hers and, for the time being, we were locked out. A life-size horse statue was the only thing visible through the glass windows, like one of Smith’s lyrics come to life. Someone came a few minutes later to open the door, and we stepped into the cool interior to discuss Smith’s new memoir, Bread of Angels.

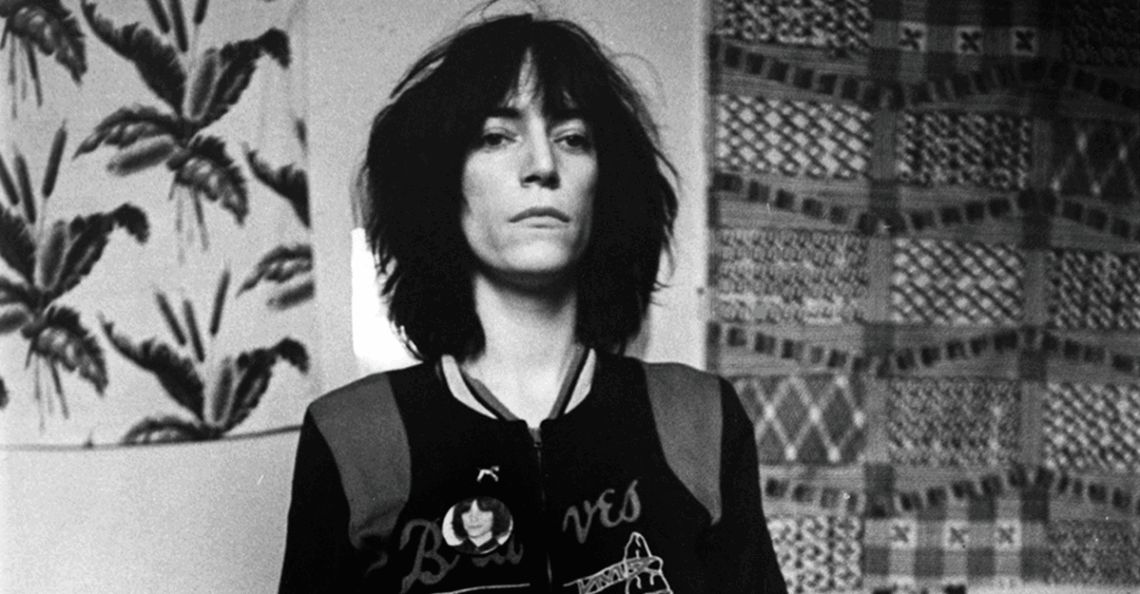

Smith, who turns 79 in December, was preparing for a busy fall ahead: the release of her memoir, an international concert tour to mark the 50th anniversary of her seminal album, Horses. In addition to reading the book, I’d spent the preceding weeks listening to her songs on repeat, and one lyric in particular seemed like it might be a kind of key to her career, which over the course of six decades has comprised poetry and performance, memoir and drawing, photography and painting, an induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and a National Book Award. “People say, ‘Beware,’ but I don’t care,” she sings defiantly in the first track on Horses. “The words are just rules and regulations to me.” After a pause she repeats the last word, elongating the vowel for emphasis: “Meeeeee.”

I already knew that she started chafing early on against authorities and edicts. Smith writes in the memoir about a question that came to her as she sat in Bible study in South Jersey at the dawn of the 1960s: What will happen to art? Her father, Grant—the man who taught her to question everything—had recently taken their family of six to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He was a fan of Dalí; Patti, 12, was captivated by Picasso and cubism. Now, listening to a Jehovah’s Witness elder describe the coming apocalypse, she couldn’t shake the image of museums in flames: “sculpture, great architecture, to say nothing of Picasso’s paintings.” Who would rescue the art?

Her mother, Beverly, had joined the Witnesses after her own father’s sudden death, drawn to the promise of a reunion in the New World. Smith was attracted to the Witnesses’ status as outsiders; on Saturdays, she forswore cartoons to go door-to-door and preach the good news, relishing the hostile reception the proselytizers often got. Already wary of pledging her allegiance to anything, she didn’t mind that the religion forbade saluting the flag at school. But there was no satisfying answer to the problem of the art. When she brought it up with another elder, she “was told that there was no place for art in Christ’s Kingdom.” And so “I cast off my religion”—not without regret—and “gave my evolving self to art.”

I hoped to understand more, talking to Smith, about that double me. Did it represent a certain self-involvement, or a profound self-confidence, a desire to not only break others’ rules but write her own? Her interests could hardly be more eclectic. She checks in daily with Pope Leo’s latest statements, she told me (“He’s a measured man, he’s intelligent”). She watches Al Jazeera and reads The Times of Israel. She inhales detective shows, especially British ones, and takes writing breaks to listen to “Ride,” by Lana Del Rey, four times in a row. She has probably read Arthur Rimbaud’s prose poem A Season in Hell more than any other nonacademic alive. On Substack, she is beloved for her video musings on topics as diverse as Jimi Hendrix, Nikolai Gogol, and her cat. She has 1.4 million Instagram followers.

Smith and I sat on a green velvet couch drinking (very good) oat-milk matcha lattes, which seemed a bit on the nose as emblems of a city that has changed drastically since Smith first stepped off the bus at Port Authority with her plaid suitcase at age 20, in 1967.The decade of Smith’s life that followed is well known, practically mythological, thanks largely to her 2010 memoir, Just Kids, which has sold more than a million copies in the U.S.: her relationship with the artist Robert Mapplethorpe, the bohemian coterie at the Hotel Chelsea, the poetry reading at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery accompanied by electric guitar that unexpectedly led to rock stardom.

Just Kids is a chronicle of young love and freewheeling artistic experimentation in a New York City where, as Smith writes, “fifty cents was real money” and you might run into Dalí himself, or befriend Allen Ginsberg, or fall for the playwright Sam Shepard before realizing he was married (Smith did all of that). The book works as well as it does because of its fairy-tale-like focus on its two singular protagonists, fated for greatness and tragedy. Although it ends with Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS in 1989, at age 42, virtually none of the narrative takes place later than 1974. It is not a book about what unfolded after that for Smith—about being famous, or a mother, or a widow. Fifteen years ago, Smith told me, she wasn’t sure if she would ever be able to write about her late husband, the musician Fred “Sonic” Smith—the man whom, she writes in Bread of Angels, “I loved for a time more than myself.”

If Just Kids is about innocence and ambition, Bread of Angels—a sister to that book, Smith told me—deals with the more painful realities of experience. She fills in what the earlier memoir leaves in the background: her childhood, her marriage, her fame. There turned out to be a twist. When Smith had already written most of the manuscript, she stumbled onto revelations about her family that upended her sense of self. “I had to really think about the truth of my life,” she told me. “And what I had thought was not so.”

Picasso was on her mind once more as she wrote. She approaches nonfiction in the spirit of cubism, she said: “You look at all different angles of the same face.” And if you’re Smith, an editor lets you get away with prose that uninhibitedly shifts registers, veering from detailed memories into something close to magical realism and back. Smith’s ever-present sense of destiny, her mystical optimism, and her penchant for rebellion make for reminiscences that can sound at once bombastic and humble, half-invented and visceral. It struck me that the need she felt, nearing 80, to tell a new story of her very existence was perhaps perfectly in keeping with a lifetime of reinvention.

In Smith’s baby book, her mother wrote down two of her early questions: What is the soul? What color is it? Beverly, a waitress who had another daughter and then a son in the two years after Smith was born (and eventually one more daughter), had little time for her eldest’s metaphysical ponderings. Money was tight, especially when Smith’s father, who worked as a machinist after returning from World War II, was on strike. The family faced eviction on several occasions and moved more than a dozen times before Smith was 8, mostly around the Philadelphia area, before settling in South Jersey. She was often sick—pneumonia, tuberculosis, German measles, mumps, chickenpox, scarlet fever.

Convalescing, she would lie in bed, “picturing the characters in my books, spinning them adventures beyond the page.” With each illness, “I was privileged with a new level of awareness,” she writes in Just Kids, describing her feverish hallucinations. Even the derelict setting of the temporary “barracks” where the family lived for a time in Philadelphia seems somehow lovely in that book, “an abandoned field alive with wildflowers.” In Bread of Angels, she widens the frame. We learn of the bleakness surrounding the field: “a concrete area with overflowing trash bins, oil barrels, rusted cans, and discarded junk.” The children played in a crawl space “dotted with the red eyes of large city rats.”

At school, Smith was a misfit, but at home, as the oldest, she was the proud leader of her siblings, her first crew and audience. The loyal troupe fought with bullies and acted out Smith’s tales, some of which were loosely based on her favorite books (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Little Women, Nancy Drew). “I learned how to tell stories from my mother, who just had a natural affinity,” she told me. Her father loved reading poems aloud to the family. When Smith got in trouble for missing school one day—she’d been waylaid communing with a turtle in a pond where she felt sure spirits lived—Beverly was angry, but Grant understood.

She loved her family, but had a sense of being and looking different from the others. As a girl, scanning for resemblance among snapshots and mementos, Smith noticed an old newspaper clipping of her father winning a race as a young man, and saw herself in it; she was also a fast runner, one who yearned to break through ribbons. Looking at the photo, she said to herself, This is who I am. I am you. She kept it in a tin frame for years.

Yet Smith’s ambitions were more literary than athletic. “I believed I could write the longest book in the world,” she recalls in Bread of Angels, inhabiting a grandiose young self. “I would record the events of every single day. I would write it all down in such a way that everyone would find something of themselves.”

Fame and fortune, Smith insists, were never her primary objectives—making art was. She worked hard, but she portrays herself as not so much a hustler as a believer in the power of fate. “I don’t know how to play guitar,” she said in a 1976 interview, “but I just get in a perfect rhythm and I play. I don’t care.” The risk of sabotaging commercial success evidently didn’t deter her. After “Because the Night,” the 1978 song she co-wrote with Bruce Springsteen, became a hit, she declined promotional opportunities and refused to lip-synch the song on Dick Clark’s show; doing so seemed inauthentic. “The single quickly slid off the charts,” she writes in Bread of Angels. “It appeared I had been somewhat naïve in believing one got successful solely by their own merit.” When her label urged her to take the word heroin out of “Dancing Barefoot” so that it could be played on the radio, Smith would not comply (she said that she was actually singing heroine; she was always squeamish about needles and tended to stay away from hard drugs).

Smith wasn’t trying to produce chart-toppers anyway. Her songs—influenced by rock, punk, and reggae—are striking and confident and cathartic, but unconventional in ways that challenge the casual listener. Some feature layered tracks of exploratory spoken word that seem almost improvisational; elsewhere, her lyrics showcase her magpie-like poeticism, with echoes of Rimbaud, William Blake, Sylvia Plath, the Beats.

While on tour in Detroit in 1976, Smith met the man she would marry, and immediately felt “a gravitational force.” She was starting to dislike the person she was becoming, she told me: “demanding, presumptuous, and agitated.” Smith said that although she hated to “play the gender card,” she realizes now that the take-no-prisoners persona she was developing was probably a necessity as a rare front woman in a male-dominated scene. “People like to look at me as this tough, punky shit-kicker,” she told an interviewer in 1975 during a recording session for Horses. “Well, I am like that,” she said. “But I’m also very fragile.” By the end of the 1970s, she knew she had to walk away. And so she did, leaving New York for a private life with Fred in a suburb of Detroit, his hometown.

The couple bought a stone house covered in vines, and a boat that Fred hoped to take out on the water but never did. Instead, they sat inside the boat in their yard and listened to baseball games, to Beethoven and Coltrane. Baseball and boats were Fred’s passions, but Smith readily followed his lead. “Soon after we were married,” she writes, “Fred expressed the wish for a son. I hadn’t thought of having children.”

When she got pregnant, Smith was certain she would have a boy, and she did; they named him Jackson. A similar sequence played out, in her telling, with their daughter, Jesse, born five years later. All of it—having children because her husband wanted them, putting her career on hold to tend pear trees in a midwestern suburb—might come across as out of character for Smith, who spent her formative years subverting traditional gender roles. At the same time, her portrayal of the interlude as fated, and fulfilling thanks in part to that feeling, is pure Smith.

She derived real satisfaction from motherhood, and still does. (Both Jackson, now 43, and Jesse, 38, regularly perform with her.) The constraints of parenting young kids forced her to focus on writing prose and poetry in Michigan, she told me, but she never fully abandoned music. She and Fred played together at home and produced an album in New York in the late ’80s. (It flopped, though a song on it—“People Have the Power”—has endured.) Fred “was a troubled man,” Smith writes, “but I was never to penetrate the true nature of those troubles.” Elliptical about the details of the chronic health struggles he faced, she calls his decline “the tragedy of my life.”

Fred died in November 1994 of heart failure. The next month, Smith’s beloved brother, Todd, had a stroke while wrapping Christmas presents and died. After returning to New York with her kids, Smith began work on a new album and went on tour with Bob Dylan. People seemed to assume that she had spent the preceding years doing nothing, a perception that still bothers her. “Just because I’m not on the stage somewhere or you haven’t read an article about me does not mean that I don’t exist as a conscious being who’s evolving creatively, intellectually,” she told me.

In Michigan, she had formed a family and written “a million words” at her kitchen table each morning, a kind of self-apprenticeship. Without that practice, she would never have written Just Kids. “So, I would say, time well spent.”

Near the end of our conversation, Smith brought up her desire, invoked early in her memoir, to write something in which everyone would find a piece of themselves. It was a goal she hadn’t fulfilled, she acknowledged. “Nobody knows how anybody feels,” she said. But she hoped this new book would at least remind her readers, “You’re not alone.”

In the penultimate chapter of Bread of Angels, she describes the shock of learning, at age 70, that her biological father was not Grant Smith, but another World War II veteran, “a handsome gunner from the 766th Bombardment Squadron” whom Smith speculates her mother may have met at a nightclub while Grant was out of town. The gunner’s heritage was 100 percent Ashkenazi Jewish. As a girl, Smith had fantasized about being from a tribe of nomadic aliens or Native Americans. Now she found that she was descended quite literally from a wandering people.

Smith chose to write about her discovery not to reveal some great secret or proclaim a new identity. “Who cares whether I’m Ukrainian Jewish or Scotch Irish?” she said to me. “But what I do relate to is the idea of a people who have been constantly displaced”—perhaps not a universal experience, but an all-too-common one.

This genuine desire to speak broadly to the human condition can veer, at times, toward New Age self-help. “How can we leap back up” after hardship? Smith asks in Bread of Angels.

By returning to our child self, weathering our obstacles in good faith. For children operate in the perpetual present, they go on, rebuild their castles, lay down their casts and crutches, and walk again.

The sentiment sounds gauzy, and then you remember the subtext. Smith wasn’t just a dreamy kid. She was also defiant, intent on doing things her way—the words are just rules and regulations to me—hard and weird though that way could be. Setbacks could also present artistic possibilities. This is still how she sees the world: Beware ? Why? “I just do what I want,” she said in 2022. “Or I don’t do it.”

This is why people watch Smith on Substack as she reads children’s stories out loud in the dark or flips through her old passports; it’s why they ask her to sign copies of Just Kids at concerts. Maybe, her fans hope, by spending time with Smith, they, too, will take on some of this toughness tinged with wonder, this ability to revisit past selves and to carry on, come what may.

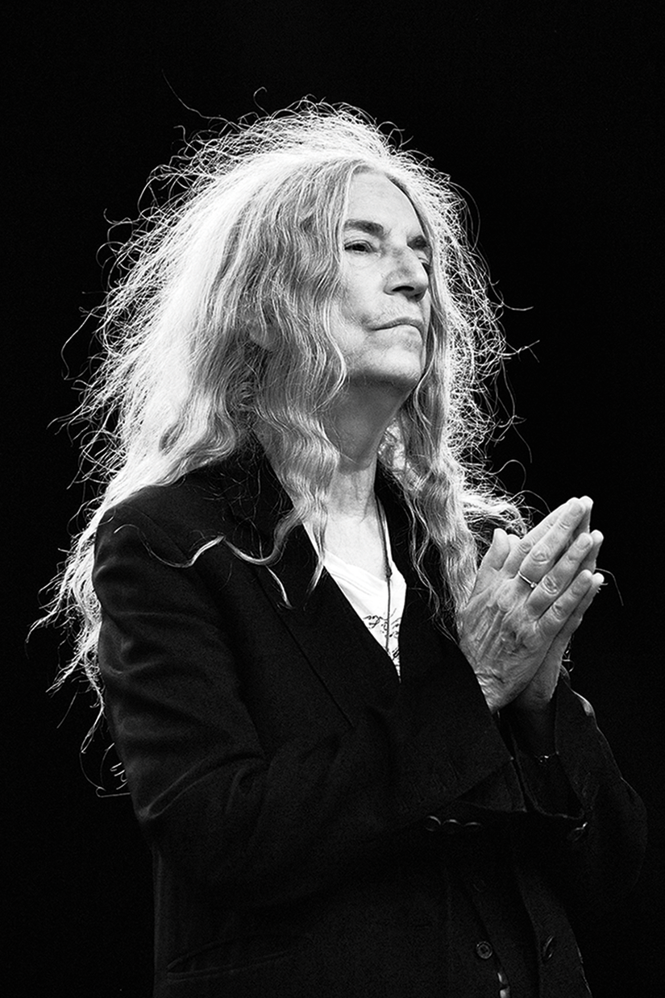

As Smith and I talked that afternoon at the gallery, the low light made everything in the airy space feel somehow outside of time. Smith’s face, I noticed, was barely lined. Her plans sounded fluid. She’s ready to disappear into prose less tethered to reality, she said. Bread of Angels will be her last memoir; she’s working on a Japanese detective story and a book called The Melting, and other things she wasn’t ready to tell me about. When I asked her how old she felt, she didn’t hesitate. “Ten and 100,” she said. She laughed, then assured me that she really meant it.

This article appears in the December 2025 print edition with the headline “Patti Smith’s Lifetime of Reinvention.”

The post Patti Smith’s Lifetime of Reinvention appeared first on The Atlantic.