Hurricane Melissa was among the worst-case scenarios Jamaica could have imagined. The storm’s winds flattened crop fields, homes and businesses. Its rains washed away trees, roads and cars.

And yet, the Caribbean island appears surprisingly well-placed to weather at least the financial cost of the damages.

In recent years, Jamaica has created a multilayered financial plan to respond to natural disasters. The strategy, which analysts say is uncommonly sophisticated, means the government has an arsenal of financial reserves and other tools ready to deploy, with each designed to handle a different level of disaster.

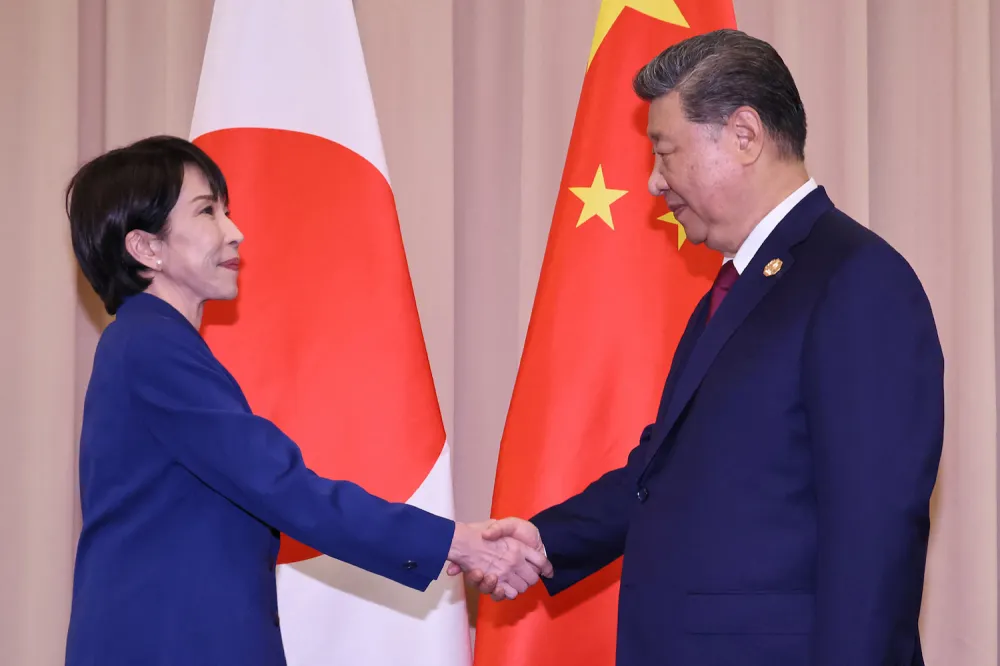

“We can’t prevent the storms and hurricanes that come at us,” Fayval Williams, the country’s finance minister, said at a news conference on Thursday. “But one thing this government can be credited with is putting together a robust national natural disaster risk financing policy.”

This year, the various tools should amount to about $820 million, Ms. Williams said in June.

Jamaicans typically don’t carry much in the way of property insurance. But with 82 percent of the country’s population living within a few miles from the coast, according to the World Bank, and most industries and services located in flood-prone areas, extreme weather poses immense risks to Jamaicans and their economy. So designing a plan to increase government spending after a natural disaster, analysts say, was needed to keep the economy going.

Keenan Falconer, a Jamaican economist who previously worked as an analyst for the country’s finance ministry, said that during past crises, the government’s hands were tied. The first response would be to rearrange the budget to fund relief efforts.

“What that inevitably means is that development is interrupted,” Mr. Falconer said. “The school or hospital that you were planning to build cannot be built because you have to put the fiscal resources elsewhere.”

The first line of defense in Jamaica’s multilayered financial fortress includes national disaster and contingency funds, pools of money the government has already funded and can be used to pay for immediate needs, like creating shelters and buying emergency supplies.

The next layers would involve making claims against a Caribbean insurance pool and activating preapproved loans from international organizations like the World Bank. A $150-million catastrophe bond — a financial tool that essentially transfers the risk from Jamaican taxpayers to global investors — is the top layer, reserved for the most catastrophic events.

“If the layers are exhausted,” Ms. Williams told reporters, “we can continue to the next layer.”

The catastrophe bond has a high bar, and is set with such precision regarding a storm’s intensity and geographic position that Jamaica was disappointed to learn last year that Hurricane Beryl did not trigger the fund when it passed close by the southern coast as a Category 4 storm. At the time, the storm caused an estimated $995 million in damages, including widespread crop losses in St. Elizabeth parish, the country’s breadbasket, where Melissa made landfall.

But Melissa appears more likely to surpass those stiff requirements.

“Hurricane Melissa will be the true test of whether or not Jamaica insured itself by being fiscally responsible,” said Mikol Mortley, a Jamaican economist and financial analyst. “But one thing I know for certain is that we are better off today than we were last year with Beryl, in 2004 with Ivan and in 1988 with Gilbert.”

But with some analysts and disaster modelers estimating that the economic losses in Jamaica could reach between $2 billion and $8 billion, representing potentially about a third of the country’s gross domestic product, some fear that even Jamaica’s sophisticated scheme will be overwhelmed.

It would be impossible for the disaster risk financing tools to finance all reconstruction, analysts said, as they are only designed to get the economy back on its feet and fund emergency repairs — key bridges, hospital roofs, major roads, school buildings.

“Disaster risk financing proceeds cannot solve every problem,” said Mr. Falconer, but it improves the government’s capacity “to respond to affected citizens.”

Long-term reconstruction is expected to be financed mainly by internal resources over time, but Ms. Williams, the finance minister, said Jamaica will also look for international aid.

The latest storm may also put pressure on Jamaica’s economy. About a decade ago, the country was one of the world’s most indebted nations. Since then, a painful fiscal discipline program has put the country on more stable financial footing.

“We were expected to hit our debt-to-G.D.P. target this year,” said Mr. Mortley. “Will this place that out of alignment? We don’t know.”

Emiliano Rodríguez Mega is a reporter and researcher for The Times based in Mexico City, covering Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

The post Jamaica Prepared a Financial Fortress for Disaster. Hurricane Melissa Will Test It. appeared first on New York Times.