The federal food assistance program now at the center of a legal battle during the government shutdown serves nearly 42 million people. It pays for groceries for one in eight Americans, and more than one in three households in counties that rely the most on it.

The administration had said it would not tap contingency funds to keep the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program operating as of Saturday, threatening to halt benefits for the first time in the program’s modern history. On Friday, two federal judges initially sided with Democratic-led states and local organizations who sued to force the U.S. Department of Agriculture to pay benefits. But families now enter November not knowing how quickly any funds may arrive, whether they’ll be reduced in scale or how long the legal wrangling will last.

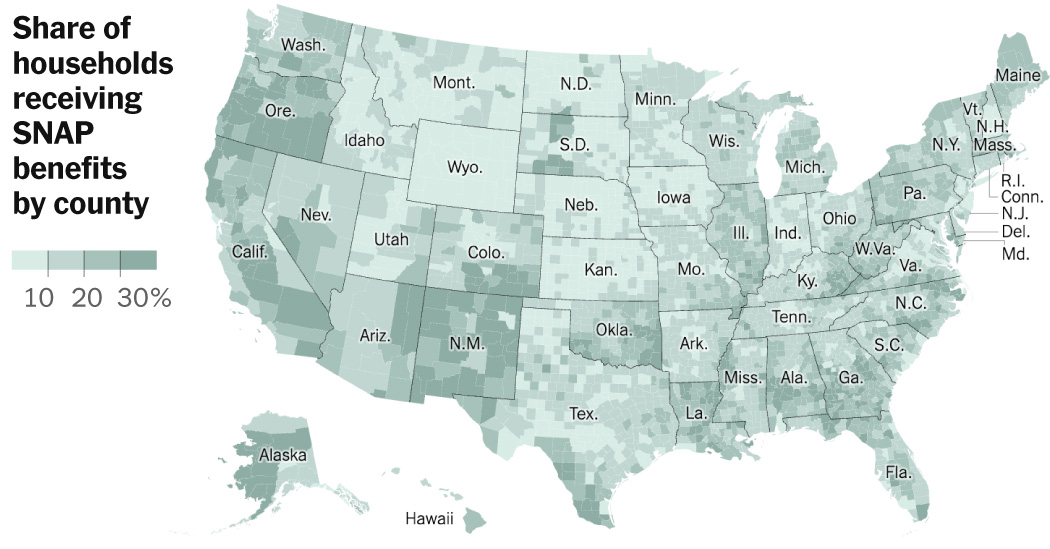

Here’s just how wide-reaching the program is, according to a New York Times analysis of government data:

Households and local economies depend heavily on SNAP on Native American reservations in South Dakota, in high cost-of-living cities like New York, and in parts of Alaska with limited grocery retailers. It’s prevalent where there are many low-paying hospitality jobs in parts of Florida, as well as in farming communities in California’s Central Valley.

This widespread use, touching nearly every part of the country, means that any disruption to SNAP benefits threatens to accelerate pain from the shutdown nationwide. But in keeping with other moves by the Trump administration during the budget impasse, its attempt to cut off food aid could also have a disproportionate political impact in Congress.

Among the 50 congressional districts with the highest SNAP participation rates, 43 are represented by Democrats (this includes Arizona’s Adelita Grijalva, who has not yet been sworn in).

By putting pressure on programs and constituencies Democrats have championed — while shuffling money to fund its own priorities — the administration has sought to punish its partisan opponents during the shutdown. But food assistance has a far broader and more bipartisan reach than, say, blue-state infrastructure projects that the administration has canceled during the shutdown.

Other parts of the country that are also heavily reliant on SNAP supported Mr. Trump in the 2024 election, including much of Appalachia, predominantly Hispanic Texas border counties that swung to the right last year, and rural counties across the South and West.

Two-thirds of all people in the program are either children; adults over 60; or adults with disabilities, according to U.S.D.A. data. And among the remaining adults, most work.

Food assistance, formerly known as food stamps, has served to backstop Americans in low-wage jobs. A study surveying several states by the Government Accountability Office in 2020 found that about 70 percent of adult wage earners in the program worked full-time hours, most commonly in education and health services, hospitality and retail. (Walmart, in addition to receiving SNAP funds from shoppers, was also among the largest employers of workers who use the program.)

SNAP benefits, about $187 a month on average, have particularly rapid economic effects because they travel quickly from the federal government to debit cards used by households to corner stores, farmer’s markets, grocers and supermarkets around the country. Supermarkets and “super stores” collect about 75 percent of all SNAP payments.

Heading into the shutdown, the administration said that contingency funds could be used to cover food aid in the event of a lapse in funding from Congress. But the administration shifted its position and has argued in court that it cannot logistically and reasonably make November payments that would total about eight billion dollars.

The administration’s move to halt SNAP during the shutdown comes after Republicans passed steep cuts to the program in their major domestic policy bill over the summer. Arguing that food assistance was riddled with waste and fraud, Republicans expanded work requirements and shifted more of the expense of the program onto states. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the changes will push states to reduce or eliminate benefits, with 2.4 million people falling out of the program because of the work requirements alone.

About the data: To calculate SNAP participation rates by county and congressional district, we used U.S.D.A. administrative data on the number of SNAP recipient households in each state as of May 2024. We then allocated those households to counties or congressional districts within each state according to their share of state SNAP household recipients in 2019-23 five-year American Community Survey data. A.C.S. data typically undercounts participation in safety-net programs, and so this methodology tries to correct for that. Because our total household count data slightly lags 2024 administrative data on SNAP use, our participation rate estimates may be slightly high in rapidly growing places (and slightly low in shrinking places). And estimated participation rates may be off more in counties with few SNAP recipients.

Emily Badger writes about cities and urban policy for The Times from Washington. She’s particularly interested in housing, transportation and inequality — and how they’re all connected.

Amy Fan is a Times reporter and a member of the 2025-26 Times Fellowship class, a program for journalists early in their careers.

The post Here’s Who Will Be Affected by Disruptions to Federal Food Aid appeared first on New York Times.