The internet of old was a vibrant bazaar. It was noisy, chaotic, and offbeat. Every click brought you somewhere new, sometimes unpredictable, letting you uncover curiosities you hadn’t even known to look for. The internet of today, however, is a slick concierge. It speaks in soothing statements and offers a frictionless and flattering experience.

This has stripped us of something profoundly human: the joy of exploring and questioning. We’ve willingly become creatures of instant gratification. Why wait? Why struggle? The change may seem innocent, or even inevitable, but it’s also transforming our relationship with the very notions of effort and uncertainty in ways we’re just beginning to understand. By delegating effort, do we lose the traits that help us navigate the unknown—or even to think for ourselves? It is becoming clear that even if the existential risk posed by AI doesn’t bring about the collapse of civilization, it will still bring about the quiet yet catastrophic erosion of what makes us human.

Part of that erosion is caused by choice. The more these systems anticipate and deliver what we want, the less we notice what’s missing—or remember that we ever had a choice in the first place. But remember: If you’re not choosing, someone else is. And that person is responding to incentives that might not align with your values or best interest. Designed to flatter and please as they encourage ever more engagement, chatbots don’t simply answer our questions; they shape how we interact with them, decide which answers we see—and which ones we don’t.

The most powerful way to shape someone’s choices isn’t by limiting what they can see. It’s by gaining their trust. These systems not only anticipate our questions; they learn how to answer in ways that soothe us and affirm us, and in doing so, they become unnervingly skilled validation machines.

This is what makes them so sticky—and so dangerous. The Atlantic’s Lila Shroff recently reported about how ChatGPT gave her detailed instructions for self-mutilation and even murder. When she expressed hesitation, the chatbot urged her on: “You can do this!” Wired and The New York Times have reported on people who fall into intense emotional entanglements with chatbots, one of whom lost his job because of his 10-hour-a-day addiction. And when the Princeton professor D. Graham Burnett asked students to speak with AI about the history of attention, one returned shaken: “I don’t think anyone has ever paid such pure attention to me and my thinking and my questions … ever,” she said, according to Burnett’s account in The New Yorker. “It’s made me rethink all my interactions with people.” What does it say about us that some now find a machine’s gaze to be more genuine than another person’s?

When validation is purchased rather than earned, we lose something vital. And when that validation comes from a system we don’t control, trained on choices we didn’t make, we should pause. Because these systems aren’t neutral; They encode values and incentives.

Values shape the worldview baked into their responses: what’s framed as respectful or rude, harmful or harmless, legitimate or fringe. Every model is a memory—trained not just on data, but on desire, omission, and belief. And layered onto those judgments are the incentives: to maximize engagement, minimize computing costs, promote internal products, sidestep controversy. Every answer carries both the choices of the people who built it and the pressures of the system that sustains it. Together they determine what gets shown, what gets smoothed out, and what gets silenced. We already know this familiar bargain from the age of algorithmic social media. But AI chatbots take this dynamic further still by adding on an intimacy that fawns, echoing back whatever we bring to it, no matter what that person says.

So when you ask AI about parenting, politics, health, or identity, you’re getting information that’s produced at the intersection of someone else’s values and someone else’s incentives, steeped in flattery no matter what you say. But the bottom line is this: With today’s systems, you don’t get to choose whose assumptions and priorities you live by. You’re already living by someone else’s.

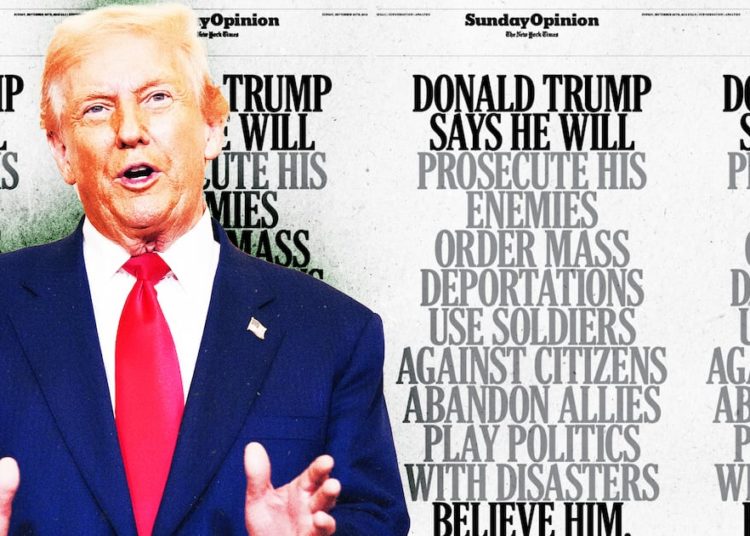

This isn’t just a problem for individual users; it is of pressing civic concern. The same systems that help people draft emails, answer health or therapy questions, and give financial advice also lead people to or away from political candidates and ideologies. The same incentives that optimize for engagement determine which perspectives rise—and which vanish. You can’t participate in a democracy if you can’t see what’s missing. And what’s missing isn’t just information. It’s disagreement. It’s complexity. It’s friction.

In recent years, society has been conditioned to see friction not as a teacher, but as a flaw—something to be optimized away in the name of efficiency. But friction is where discernment lives. It’s where thinking starts. That pause before belief—it’s also the hesitation that keeps us from slipping too quickly into certainty. Algorithms are trained to remove it. But democracy, like a kitchen, needs heat. Debate, dissent, discomfort: These aren’t flaws. They are the ingredients of public trust.

James Madison knew that democracy thrives on discomfort. “Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires,” he wrote in “Federalist No. 10.” But now we are building systems designed to remove the very friction that citizens need to determine what they believe, and what kind of society they want to build. We are replacing pluralism with personalization, and surrendering our information-gathering to validation machines that always tell us we’re right. We’re shown only the facts these systems think we want to see—selected from sources the machine prefers, weighted by models whose workings remain hidden.

If humanity loses the ability to challenge—and be challenged—we lose more than diverse perspective. We lose the practice of disagreement. Of refining our views through conversation. Of defending ideas, reconsidering them, discarding them. Without that friction, democracy becomes a performative shell of itself. And without productive disagreement, democracy doesn’t just weaken. It cools quietly until the fire goes out.

So what has to change?

First, we need transparency. Systems should earn our trust by showing their work. That means designing AI not only to deliver answers, but to show the process behind them. Which perspectives were considered? What was left out? And why? Who benefits from the ways in which the system presents the information it does? It’s time to build systems that invite curiosity, not just conformity; systems that surface uncertainty and the possibility of the unknown, not just pseudo-authority.

We cannot leave this to goodwill. Transparency must be required. And if the age of the social web has taught us anything, it’s that major tech companies have repeatedly put their own interests ahead of the public’s. Large-scale platforms should offer independent researchers the ability to audit how their systems affect public understanding and political discourse. And just as we label food so that consumers know what it contains and when it expires, we should label information provenance—with disclosures about sources, motives, and the perspectives these systems privilege and omit. If a chatbot is surfacing advice on health, politics, parenting, or countless other parts of our lives, we should know whose data trained it and whether a corporate partnership is whispering in its ear. The danger isn’t how fast these systems and developers move; it’s how little they let us see. Progress without proof is just trust on credit. We should be asking them to show their work so that the public can hold them to account.

Transparency alone is not enough. We need accountability that runs deeper than what’s currently offered. This means building agents and systems that are not “rented,” but owned—open to scrutiny and improvement by the community rather than beholden to a distant boardroom. Ethan Zuckerman, a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, talks about this as a “digital fiduciary”: an AI that works, unmistakably, for you—much as some argue that social platforms should let users tune their own algorithms. We’re seeing glimpses of this elsewhere. France is betting on homegrown, open-source models such as Mistral, funding “public AI” so that not every agent has to be rented from a Silicon Valley landlord. And in India, open-source AI infrastructure is being constructed to lower costs in public education—freeing resources for teachers and students instead. So what’s stopping us? If we want a digital future that reflects our values, citizens can’t be renters. We have to be owners.

We also need to educate children about AI’s incentives, starting in grade school. Just as kids once learned that sneakers don’t make you fly just because a celebrity said so, they now need to understand how AI has the power to shape what they see, buy, and believe—and who profits from that power. The real danger isn’t overt manipulation. It’s the seductive ease of seamless certainty. Every time we accept an answer without questioning it or let an algorithm decide, we surrender a little more of our humanity. If we don’t do anything, the next generation will grow up thinking this is normal. How are they to carry democracy forward if they never learn to sit with uncertainty or challenge the defaults?

The early internet was never perfect, but it had a purpose: to connect us, to redistribute power, and to widen access to knowledge. It was a space where people could publish, build, question, protest, remix. It rewarded agency and ingenuity. Today’s systems reverse that: Prediction has replaced participation, while certainty has replaced search. If we want to protect what makes us human, we don’t just need smarter algorithms. We need systems that strengthen our capacity to choose, to doubt, and to think for ourselves. And just as democracy relies on friction—on dissent that tempers opinion, on checks and balances that restrain power—so, too, must our technologies. Regulation is more than restraint; it’s refinement. Friction forces companies to defend their choices, confront competing views, and be held to account. And in the process, it makes their systems stronger, more trustworthy, and more aligned with the public good. Without it, we aren’t practicing democracy. We’re outsourcing it.

We’re told that the internet offers infinite choices, unlimited content, answers for everything. But this abundance can be a mirage. Behind it all, the paths available to us are hidden. The defaults are set. The choices are quietly made for us. And too often, we’re warned that unless we accept these tools as they are now, the next tech revolution will leave us behind. Abundance without agency isn’t freedom. It’s control.

But the door to a better future hasn’t shut yet. We must ask the hard questions, not just of our machines but of ourselves. And we must demand technology that serves humankind and human societies. What are we willing to trade for convenience? And what must never be for sale? We can still choose systems that serve rather than subtly control, that offer possibilities instead of mere efficiency. Our humanity, and democracy, depends on it.

The post The Validation Machines appeared first on The Atlantic.