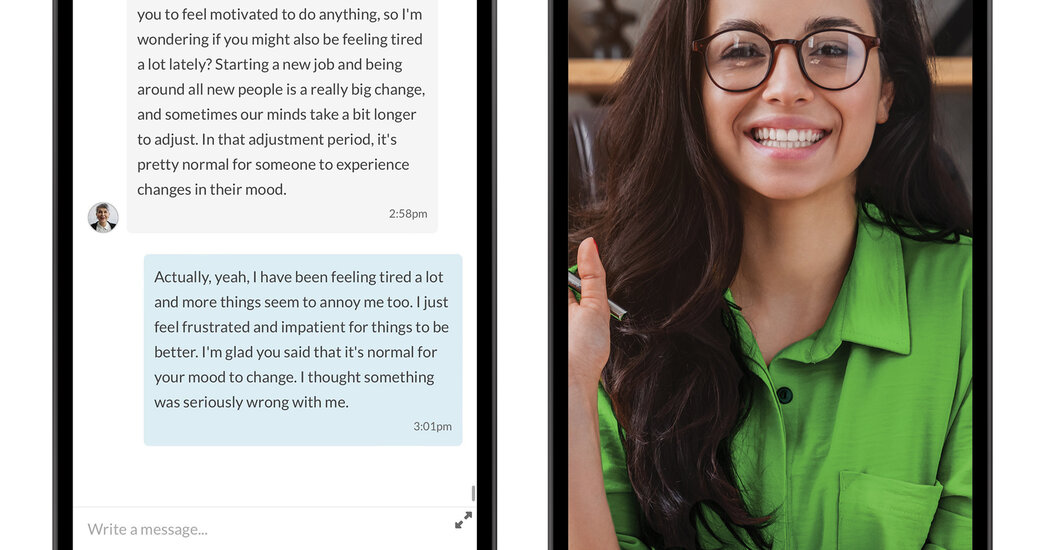

One of the most popular mental health innovations of the past decade is therapy via text message, which allows you to dip in and out of treatment in the course of a day. Say you wake up anxious before a presentation: You might text your therapist first thing in the morning to say that you can’t stop visualizing a humiliating failure.

Three hours later, her response pops up on your phone. She suggests that you label the thought — “I’m feeling nervous about my presentation” — and then try to reframe it. She tells you to take a deep breath before deciding what is true in the moment.

You read her answer between meetings. “I’m pretty sure my boss thinks I’m an idiot,” you type. The therapist responds the next morning. “What evidence do you have that she thinks that?” she asks. She tells you to write a list of the available evidence, pros and cons.

Text-based therapy has expanded swiftly over the past decade through digital mental health platforms like BetterHelp and Talkspace, which pair users with licensed therapists and offer both live chat and as-needed texting sessions. A new study published on Thursday in the journal JAMA Network Open provides early evidence that the practice is effective in treating mild to moderate depression, finding outcomes similar to those of video-based therapy.

In a clinical trial, 850 adults with mild to moderate depression were randomly assigned to two groups: One group received psychotherapy via a weekly video session; the other received unlimited, as-needed messaging or emailing with a therapist. After 12 weeks, participants in both groups reported similar improvement in depression symptoms.

“We were pleasantly surprised to see that it was as good as weekly video therapy,” said Patricia A. Areán, a former professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine and a co-author of the study, of text-based psychotherapy. “We didn’t really find any differences in the outcomes.”

The trial was not an equivalence trial, designed to establish that the two methods were equally effective, but instead sought to determine whether video-based or text-based therapy was superior. The study provides limited information about participants, so we do not know the duration of their depression, how they were originally diagnosed, or whether they received other treatments, like antidepressants, during the trial.

Dr. Areán said that Talkspace had approached the research team in the hope of collaborating on a randomized clinical trial, for a practical reason: Though text-based therapy is a fast-growing service, most insurers still do not reimburse providers for it.

“They knew that they needed data,” she said.

She said the results suggest that insurers should reimburse providers for text-based therapy, which could expand access for people who have difficulty attending video appointments.

Dr. Jane M. Zhu, an associate professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University who was not involved in the study, said the new evidence was “encouraging,” but not yet sufficient to justify changes by insurers.

She noted that the study excluded higher-risk patients, like those coping with psychosis or suicidal thoughts, and did not track variations in the treatment, like the speed or volume of therapist responses, she said.

The number of Americans receiving psychotherapy rose significantly during the pandemic, as virtual sessions replaced in-person appointments. For decades, around 3 or 4 percent of the population saw therapists; by 2021, that portion had jumped to 8.5 percent. (By comparison, the percentage of Americans taking psychotropic medication has remained relatively stable, at around 17.5 percent.)

Dr. Zhu, who studies the accessibility of medical care, said text therapy “could eventually fit into a stepped-care model,” in which patients begin with low-intensity interventions and then, if needed, progress to treatments like medication or specialist care.

Dr. Mark Olfson, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, who was not involved in the study, said the results suggest that patients with milder depression “might reasonably be offered a choice” between text- and video-based psychotherapy.

Dr. Areán said many in the mental health field have lingering concerns about the text model, because the therapist is not face to face with the patient and may miss danger signs. But there were no adverse events in the trial, she said.

The trial participants were more likely to drop out of video-based therapy than text-based.

But at the same time, the researchers reported, the video sessions appeared to create a slightly stronger bond with therapists, who were viewed by patients as warmer and more compassionate. When some participants switched from text-based to video sessions in a second phase of the trial, the quality of the bond improved significantly.

Dr. Areán said the gap in therapeutic bonding merited further research. “How do you build alliance when you can’t see the person?” she said. “How do you deal with silences when you can’t see them? Are they crying? Are they happy?”

Ellen Barry is a reporter covering mental health for The Times.

The post Study Finds Evidence That Text-Based Therapy Eases Depression appeared first on New York Times.